[Book Review Essay] Brannon D. Ingram, Revival from Below: The Deoband Movement and Global Islam (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2018). 315 pages. Paperback $26.03. Hardcover $61.81. | Reviewed by Andrew Booso

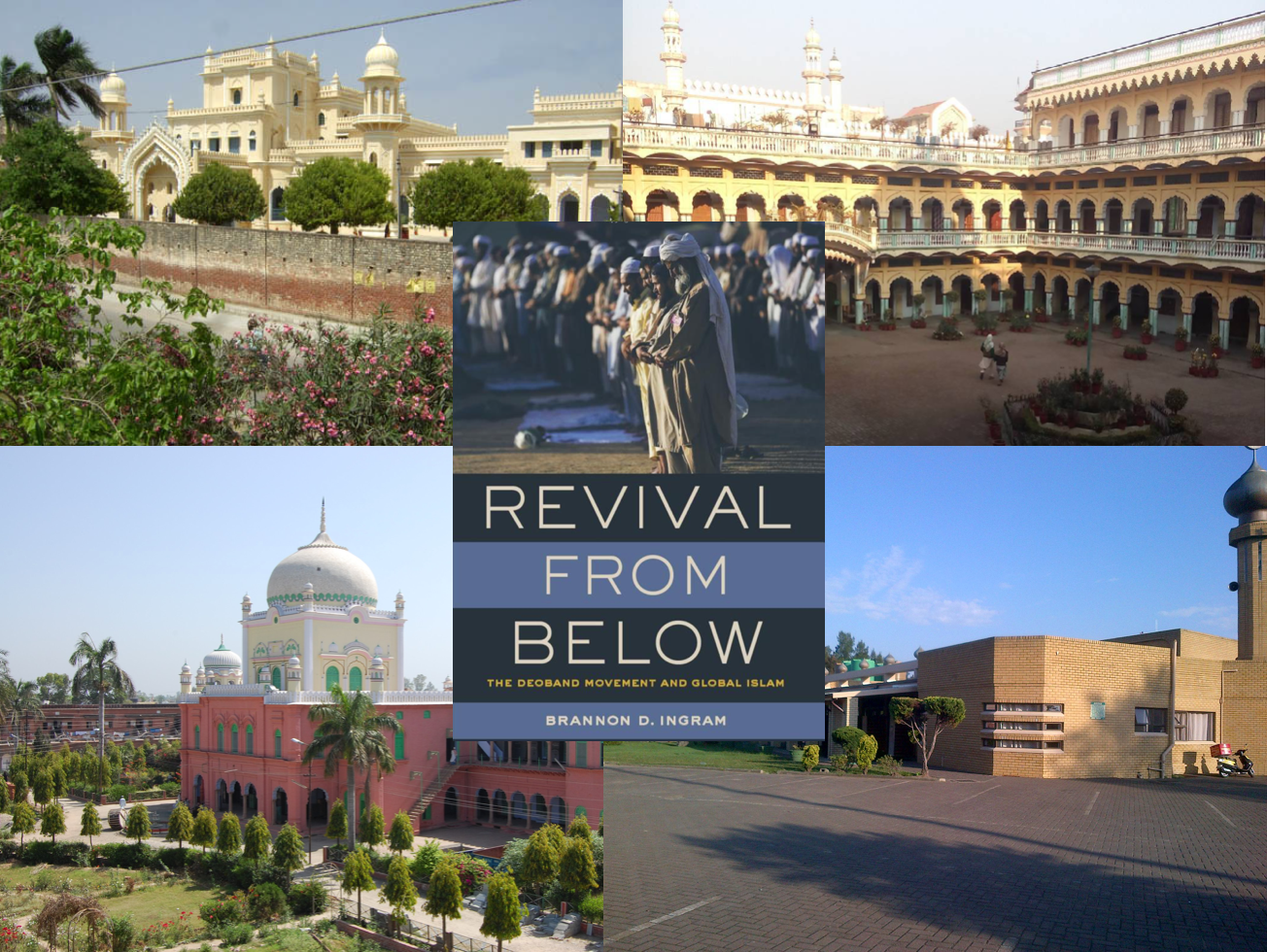

Barbara Metcalf’s seminal study on the creation of Dar al-Ulum Deoband was published in 1982 in the wake of Wilfred Cantwell Smith’s earlier declaration in Modern Islam in India (1946) that the Deoband seminary, officially founded in 1866, was second in prestige to Egypt’s al-Azhar amongst the Muslim world’s institutions of higher Islamic learning. The Deobandi educational model now boasts, in the words of Ebrahim Moosa, “the largest and fastest growing madrasa franchise.” Although Deoband started as a small religious seminary after the failure of the 1857 battle for liberation from British colonial rule, it turned into a reform movement defined by the location of the seminary that was experienced throughout India. This movement was largely apolitical and attempted to preserve Muslim life under British domination by expounding a conservative tradition, which upheld the long-accepted Sunni institutions of law, theology and spirituality, with little deviation from them. Brannon D. Ingram’s Revival from Below—which has been summarized by the author—provides a profound and invaluable study of Deobandi Sufism and how Sufism was a central feature of the Deobandi public narrative, with a groundbreaking analysis of its most prominent manifestation outside of the Indian subcontinent in South Africa [p. 4].

“Although Deoband started as a small religious seminary after the failure of the 1857 battle for liberation from British colonial rule, it turned into a reform movement defined by the location of the seminary that was experienced throughout India. This movement was largely apolitical and attempted to preserve Muslim life under British domination by expounding a conservative tradition, which upheld the long-accepted Sunni institutions of law, theology and spirituality, with little deviation from them.”

On Methodology

“Ingram’s rigorous methodology and scholarly use of sources justifies the praise on the book’s cover by Barbara Metcalf, Muhammad Qasim Zaman and Muzaffar Alam. He utilizes the main Western academic studies on the subject, … Furthermore, his utilization of less well-known South African scholars, like Abdulkader Tayob and Achmat Davids, is both welcome and important.”Ingram’s rigorous methodology and scholarly use of sources justifies the praise on the book’s cover by Barbara Metcalf, Muhammad Qasim Zaman and Muzaffar Alam. He utilizes the main Western academic studies on the subject, with the works of Metcalf, Zaman, Muhammad Khalid Masud and Ebrahim Moosa, for example, given extensive recognition. Furthermore, his utilization of less well-known South African scholars, like Abdulkader Tayob and Achmat Davids, is both welcome and important. Yet perhaps the most impressive part of his methodology is his use of a wide variety of primary sources, especially in Urdu. Whilst there are detailed discussions derived from the Urdu works of pioneers like Imdadullah, Rashid Gangohi, Khalil Saharanpuri, as well as later prominent figures like Muhammad Tayyib (sometimes spelt by authors as Tayyab), Taqi Usmani and numerous South African Deobandi figures, the “central character” in the book is “by far” Ashraf Ali Thanawi (spelt Thanvi in the book in order to accommodate the Urdu pronunciation). This focus is justified as Thanawi is the figure “who synthesized law and Sufism in a body of work that is largely responsible for making Deoband a global phenomenon.” Yet Ingram adds that Thanawi is not to be understood as representing “the Deoband movement as a whole” (p. 24). This latter observation is important, especially in light of Zaman identifying Thanawi, despite his immense influence, as “a polarizing figure within the ranks of the Deobandis” [Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Ashraf ‘Ali Thanawi: Islam in Modern South Asia, 2007, p. 11].

Internal Deobandi Disputes

Zaman writes, “The Deobandis themselves have never been a happy family” as early Deobandis disagreed on “political interests” and “matters of Sufi piety” [Zaman, Thanawi, p. 11]. Indeed, the original Deoband spilt in two in 1982, which negatively impacted its public “credibility”: the family of co-founder Muhammad Qasim Nanautwi continued to control the “new” Deoband (named Darul Uloom Waqf Deoband), with the “old” Deoband in the control of the family of Husain Ahmad Madani [see Dietrich Reetz in The Madrasa in Asia: Political Activism and Transnational Linkages; Masooda Bano in Modern Islamic Authority and Social Change, Volume 1, p. 201; and here for the version according to the “new” Deoband]. Ingram highlights differences between major Deobandi figures, including a certain nuance regarding the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (mawlud, mawlid or milad)—may God’s peace and blessings be upon him—amongst the early Deobandis. For instance, Thanawi was initially open to the general celebration, as his spiritual guide Imdadullah had practised the mawlud and he had participated in it as well, before he conformed to Gangohi’s adamant and general condemnation—see pp. 65–75. In addition, Ingram includes a discussion of the political dispute between Thanawi and Madani on how to operate under the British Raj, which is mentioned as an “interlude” [pp. 190–196].

Defining a “Deobandi”

Ingram is right in stating that the mere graduation from a Deobandi madrasa does not produce some archetypal Deobandi who propagates the “brand” [p. 204]. The “brand” is discussed in Chapter 6 in terms elaborated by Muhammad Tayyib (chancellor, or muhtamim, of Deoband from 1928 until 1980). This branding indicates an identity, in essence, as Sunni, with the “disposition” (mashrab) of the co-founders of Deoband: Muhammad Qasim Nanautwi and Rashid Gangohi, as well as adherence to the Hanafi legal school and Sufism [defined in summary form here; and more fully in Sayyid Mahboob Rizvi, History of the Dar al-Ulum Deoband, 1:325–333]. This “Deobandi” identity and “brand” distinguished such people from other groups like the Barelwis (on matters of ritual) and Shia (on matters of theology).

Outline of the Book

The monograph consists of seven chapters, with an extensive introduction and a thought-provoking conclusion, and is divided into two halves: the first focusing on Deobandism in South Asia, and the second dealing with its manifestation in South Africa. The first four chapters cover the formative period of Deobandi thought. In Chapter 1, Deoband’s inception is situated at the point where the British adopted a policy of “non-interference” in Indian “religious” affairs after the 1857 battle for independence, and the Deobandis attempted to occupy that independent Muslim religious space. In Chapter 2, Ingram explains that this latter activity aimed at maintaining the “normative order,” through a sustained effort to rebut beliefs and practices that were religiously impugned, due to their being characterized as antithetical to divine oneness (shirk) or blameworthy innovation (bid‘a). These discussions on shirk and bid‘a revolved around Deobandi pronouncements condemning aspects of the celebrations of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday—may God’s peace and blessings be upon him—and the manners associating with visiting the graves of saints (ziyarat) and commemorating their lives on the dates that they passed away (‘urs).

“The monograph consists of seven chapters, with an extensive introduction and a thought-provoking conclusion, and is divided into two halves: the first focusing on Deobandism in South Asia, and the second dealing with its manifestation in South Africa.”

In Chapter 3, Ingram shows how the central method of influencing public opinion was through the printing of reformist texts, as opposed to direct sermons, whilst always reminding the laity of their need for clerics. Chapter 4 examines how the Deobandis turned their attention to individual rectification, whereby the process was explained “almost exclusively through the vocabularies of Sufism” [p. 116]. This ethical teaching—described primarily through the terms akhlaq (“character”) and adab (“etiquette”)—included the notion that individual rectification was personally obligatory, and required companionship (suhbat) with a living master who embodied the teaching of the Quran and the Sunna and accepted masters. This spiritual instruction was barely mystical (hence Thanawi cautioned against seeking “visionary insight (kashf),” p. 129), and was “simplified” in favour of a more moderate reduction of worldly activities, rather than a severe reduction in food, sleep and social relations.

Ingram raises the issue of what is Sufism and argues it is “an ongoing site of contestation in contemporary Islam,” and that it is “a diverse, internally contested, constantly debated entity” [p. 210]. His correct reading of Deobandi Sufism enables him to see that the Deobandi “interrogation of Sufism was… an internal critique of Sufism by Sufis” [p. 13]; hence Ingram’s stance that there is a “need to resist the facile usage of terms like ‘Wahhabi’ to describe Deobandis” [p. 90]. Nonetheless, Ingram’s reference to Taqi Usmani and his father Muhammad Shafi calling for more formal study of Sufism in Deobandi seminaries is an acknowledgement that the traditional method of spiritual instruction is in need of some reform [pp. 146-7].

“Ingram raises the issue of what is Sufism and argues it is ‘an ongoing site of contestation in contemporary Islam,’ and that it is ‘a diverse, internally contested, constantly debated entity’ [p. 210]. His correct reading of Deobandi Sufism enables him to see that the Deobandi ‘interrogation of Sufism was… an internal critique of Sufism by Sufis’ [p. 13]…”

The final three chapters of the work move away from focusing on the “major themes and architects of Deoband thought” [p. 138] and explore how Deoband became a global phenomenon, with a special focus on South Africa. Chapter 5 discusses Deobandi thought as a “tradition,” and explores this concept primarily through “two pivotal sites”: first, the writings of Muhammad Tayyib (Nanautwi’s grandson), whose articulation of the Deobandi maslak (literally, “path” or “way”) was “a central category for theorizing the coherence of Deobandi tradition”; and second, the expansion of Tablighi Jama‘at (“Preaching Party”), which is now “the world’s largest Muslim revivalist movement,” whose agenda entails preaching to Muslims, not non-Muslims, and is universally apolitical (whether in Muslim majority countries or otherwise). For Ingram, the Jama‘at is “an extension of the very logic of Deoband’s program of public reform”: reforming the public whilst ideally linking them with the clerical class [pp. 139–159].

“Chapters 6 and 7 then show how Deobandi thought came to be rooted in South Africa, through the migration and visits of individual scholars between India and South Africa, and the ‘global rise of the Tablighi Jama‘at.'”

Chapters 6 and 7 then show how Deobandi thought came to be rooted in South Africa, through the migration and visits of individual scholars between India and South Africa, and the “global rise of the Tablighi Jama‘at.” The latter is shown to be the “principal engine behind the global migration of Deobandi contestations” about the “Sufi devotional practices” discussed above [pp. 160–1], which led to “pamphlet wars and even physical altercations” with Barelwi rivals in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s. In Chapter 7, this Deobandi-Barelwi rivalry in South Africa during the apartheid regime gives a fascinating context to how these public debates, over seemingly trivial matters of theology and Sacred Law, led some Muslim anti-apartheid activists to see such clerics as “myopic” and lacking a relevant political voice.

Contending the Distinction Given to Ahmed Sadiq Desai over Other Deobandis

South African Deobandi cleric Ahmed Sadiq Desai is given prominent exposure by Ingram for his anti-activist tirades. Desai’s “tone” is described as “acrid,” whereby he attempted to make use of Thanawi’s criticism of Deobandi contemporaries, like Madani, working with non-Muslim Indians against the British Raj. Ingram argues that “[m]any South African Muslims were understandably incensed by Desai,” and he was seen as “the paramount example of the ‘ulama failing to lead the Muslim community,” as “many of the ‘ulama believed silently and implicitly [with his views]” [p. 202].

There is little justification given for the distinction afforded to Desai by Ingram [in particular, pp. 196–202] to the exclusion of other equally-worthy case studies whom Ingram gives only passing reference to: firstly, there is the Deoband-trained and African National Congress (ANC) activist Ismail Cachalia [pp. 203–4], who advised Nelson Mandela (who refers to him in his Conversations with Myself), and is shown by Yousuf Dadoo to have been directly inspired, whilst a student at Deoband between 1925 and 1931, by stories of political activism by Deobandi seniors; secondly, the Muslim Judicial Council in Cape Town, including their leading jurisconsult Yusuf Karaan, who was also Deoband-trained; and thirdly, Qasim Sema [usually spelt Cassim Sema; see Muhammad Khalid Sayed in Muslim Schools and Education in Europe and South Africa], who founded the first Deobandi madrasa in South Africa in 1973, the Dar al-Ulum Newcastle, after returning to South Africa in 1944 from seminary studies at the Deobandi madrasa in Dabhel, Gujarat, India. Each of these examples breaks the stereotype of a Deobandi South African cleric. Cachalia’s political pragmatism evokes the memory of Madani, and provides a prominent alternative to the Thanawi-inspired political idealism of Desai. The Muslim Judicial Council was not wholly Deobandi, but it had a significant Deobandi presence and, as Ingram shows, declared full support for the activists against apartheid in the wake of the Soweto Uprising in 1976 [p. 179]; and this, again, opposes Thanawi’s political stance. Karaan and Sema are of particular interest because Ingram shows that both were involved in mawlud celebrations, with Sema in 1958 actually co-founding an organization, the Universal Truth Movement, which held an annual mawlud and worked with Barelwis; hence displaying tendencies that are not associated with the common Deobandi “brand.”

Furthermore, Desai’s marginality amongst even South African Deobandis is indicated by the abuse he has aimed at more mainstream fellows like Ebrahim Bham of the United Ulama Council of South Africa (UUCSA). Muslim Judicial Council members who attended a multi-faith prayer service were called “murtaddeen [sic. “apostates”]” by Desai’s Majlis [see here, and here for the result of a legal dispute between Desai and the UUCSA]. In fact, when the apartheid regime was coming to an end, members of the Deobandi-led Jamiatul Ulama South Africa (Council of Muslim Theologians, Johannesburg) joined the ANC that was going to form the new government [see Reetz, p. 97]. This supports the notion that Madani-like political pragmatism has long continued in South Africa alongside the dominant apolitical Tablighism and Thanawi-inspired political idealism, even if it was less prominent, and so it deserved more exploration in Revival from Below.

The Importance of Ethnographic Analysis

Regrettably, there is no extensive ethnographic analysis of class and culture in relation to the Deobandi forefathers or their South African descendants. The identification of a cleric or groups of clerics or followers from a particular region—such as Gujarat or Bengal or the North-West Frontier or Uttar Pradesh—might show factors that explain trends of conservatism or open-mindedness. Regarding Indian Deobandism, Masooda Bano has shown that most clerics are from “lower-middle-income families and rural areas,” which are “least integrated into the modern economy and society,” so their worldviews are limited by their lack of societal interaction; hence their concentration on the teaching of matters of ritual worship (‘ibadat), with little in-depth focus on issues of social transactions (mu‘amalat). Likewise, Bano indicates, the fact that Indian Deobandis’ “primary constituencies (students as well as followers)” are from less affluent sections of society means that this socio-economic dimension creates less cultural pressure upon clerics to move away from the “textual rigidity” that largely defines Deobandi scholarship. This is in contrast to the more cosmopolitan al-Azhar in Egypt, where one can observe a greater flexibility in the scholarship as a consequence of clerics being drawn from a diversity of backgrounds, and studying in places like the Sorbonne University, France.

In fact, “upper-middle-income” Muslims in India are “increasingly adopting Middle Eastern Islamic practices,” and not Deobandism, whose general support comes from Indian Muslims of “lower-income backgrounds” who have limited access to “alternative lifestyles”[see Masooda Bano, Modern Islamic Authority, Volume 1, pp. 198, 204–5, 207–9 and 212]. Furthermore, Metcalf, whilst analysing the city of Varanasi (Banaras), Uttar Pradesh, has shown the importance of class in shaping educational and sectarian trajectories, including its impact on Deobandism in the city [see Metcalf, Chapter 4, Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education]. In relation to Ingram’s study of South Africa, ethnographic analysis might help us understand why the Western Cape displays such diversity, with its center being Cape Town, whilst someone like Desai could operate quite successfully in the Eastern Cape primarily and around the country in pockets [cf. Muhammed Haron]. Moosa has highlighted how Tablighis have been less successful in the Western Cape due to the prominence of Indonesians and Malays, who have been in the region longer than the Indian Muslims, and it is the latter who make-up the largest proportion of Tablighis [see Moosa, Travellers in Faith:Studies of the Tablighi Jama‘at as a Transnational Islamic Movement for Faith Renewal, pp. 37 and 43–4].

Differentiating Between the Seminaries of Deoband, Saharanpur and Nadwa

One concern with Ingram’s study of Deobandism is his grouping together Dar al-Ulum Deoband, Mazahir al-Ulum Saharanpur (which also split in the early 1980s, like Deoband, along administrative lines) [see Reetz hereand here] and the Nadwat al-Ulama of Lucknow. Although these reformist endeavours are very close, they deserve demarcation because their distinctive qualities have quite far-reaching effects. Metcalf states that Mazahir al-Ulum was Deobandi but had a “more parochial style” than Deoband, and “it did not play the role in politics that Deoband did” and it “came to be considered less intellectual and more Sufi in orientation than Deoband” [Metcalf, Islamic Revival, pp. 132–3]. This variance is notable because the Mazahir al-Ulum can be seen as having a determining impact on the apolitical outlook of Tablighi Jama‘at—a point made by Muhammad Khalid Masud in his introduction to Travellers in Faith [as reviewed by Jonathan Birt].

With regards to Nadwat al-Ulama, Ingram makes only one mention of the institution, noting that it is where Ebrahim Moosa is said to have studied at Deoband and Nadwa [p. 204], with the implication being that the latter is a Deobandi institution. Of course, Deoband and Nadwa share a great familiarity such that the disciplines taught in Nadwa were “barely distinguishable from those of Deoband” [Metcalf, Islamic Revival, p.344], and that Nadwa took a “traditionalist turn” soon after its founding [see Jans-Peter Hartung]. Nonetheless, this does not detract from the essential divergence between them. Metcalf shows how Nadwa wanted to differentiate itself, both politically and intellectually, from similar “reform” movements like Aligarh and Deoband; and even Rashid Gangohi did not attend the initial gatherings of the Nadwa on account of “distrusting the institution” [see Metcalf, Chapter 8, Islamic Revival].

“Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi—a member of Deoband’s Advisory Board but the chancellor of Deoband’s ‘liberal’ rival Nadwa (as characterized by Ebrahim Moosa), and perhaps the main reason for confusing the two seminaries because of his closeness to the Deobandis and the founder of Tablighi Jama‘at (whose life was covered by him)—argued that Deoband raised the religious sentiments of Indian Muslims through its reform, but… “

Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi—a member of Deoband’s Advisory Board but the chancellor of Deoband’s “liberal” rival Nadwa (as characterized by Ebrahim Moosa), and perhaps the main reason for confusing the two seminaries because of his closeness to the Deobandis and the founder of Tablighi Jama‘at (whose life was covered by him)—argued that Deoband raised the religious sentiments of Indian Muslims through its reform, but “as far as meeting the challenge of the times is concerned, Deoband has failed to make any noteworthy contribution” due to being “conservative and tradition-bound”; and in this criticism he saw Nadwa as the vehicle for a correct reform methodology [see Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi, Western Civilization, Islam and Muslims, 1979, pp. 62-6; Mohammad Akram Nadwi, Shaykh Abu al-Hasan Ali Nadwi: His Life & Works, p. 5].

Indeed, Nadwa’s inception was also defined by the first alliance between adherents of the Hanafi legal school and the non-conformist Ahl-i Hadith movement, as proudly declared by Sayyid Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi in his address at the celebration of Nadwa’s eighty-fifth anniversary in 1975, which is a move that one did not see with Deoband and its disputatious relationship with the Ahl-i Hadith [see Metcalf, Islamic Revival, pp. 271–2, 274, 277, 279 and 284]. Furthermore, Nadwa has a trend of producing prominent freethinkers whose likeness is not known to have come from Deoband; for example, Muhammad Hanif Nadwi and Muhammad Ja‘far Nadwi Phulwarwi—the latter being the son of a founder of Nadwa—as discussed in Zaman, Chapter 3, Islam in Pakistan: A History, and in England there is my teacher Shaykh Mohammad Akram Nadwi [as discussed by Christopher Pooya Razavian in Modern Islamic Authority, Volume 1, p. 259]. In Ingram’s defence, it is a common trend to place Nadwa together with Deoband without distinguishing between the two [see Masooda Bano, ibid., p. 196].

On the Prominence of Muhammad Tayyib

It is also surprising to find Tayyib listed as one of Ingram’s “pivotal sites” for the Deobandi “brand” becoming theorized and then coherently propagated. In fact, one could argue that the maslak of Deoband was already well established before Tayyib composed a useful, but arguably sidelined, work, which is not treated as a central text for understanding Deobandism by Deobandis themselves, especially as most Deobandis are Tablighis and concentrate on more simple matters such as their “six points” [explained by Ashiq Ilahi; cf. Yousuf Dadoo, pp. 90–1]. Indeed, Moosa, in Travellers in Faith, makes not a single reference to Tayyib or his treatise on Deobandism when discussing the work of Tablighi Jama‘at in South Africa, with the inference being that they are largely insignificant in the imagination and life of South African Deobandis. Moreover, Tayyib’s political career seems more in keeping with the politics of pragmatism displayed by Madani, rather than the idealism and rejection of conventional political relations with non-Muslims exhibited by Thanawi. For example, it was Tayyib who invited the then-Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, to attend the centenary celebrations of Deoband’s establishment, which is an invitation that one could not imagine Thanawi and his ilk offering [see Reetz, p. 216; Rizvi, History, 2:364].

Deobandis as Political Minorities and Activists in Muslim Majority Contexts

Ingram’s work supports the theory that Deobandi communities generally take on an apolitical outlook when situated as a Muslim minority, whether in post-Partition India (see below) or South Africa (as shown by Ingram) or the UK [see Jonathan Birt, p. 187]. Ingram writes, on p. 203, that there have been noted Deobandi “activist currents,” including Madani, Madani’s teacher Mahmud al-Hasan and the latter’s student Ubaydullah Sindhi. [Zaman, in Chapter 3, Schooling Islam, says that Sindhi was “probably the severest internal critic Deoband has ever produced.” However, the late official Deoband record registers the emotional and positive reception he received when first visiting the seminary after his long exile from India by the British, as well as praise for his scholarship in general and his expertise on Shah Waliullah in particular—see Rizvi, History, 1:227–8 and 2:44–5.] Nonetheless, this group is an exception to the general rule of Deobandism under the British, and it was a short-lived movement, albeit one that was popular amongst students and teachers of the time at Deoband [see Rizvi, History, 1:240].

“Ingram’s work supports the theory that Deobandi communities generally take on an apolitical outlook when situated as a Muslim minority, whether in post-Partition India (see below) or South Africa (as shown by Ingram) or the UK [see Jonathan Birt, p. 187]. “

Indeed, Mahmud al-Hasan, whilst principal (sadr mudarris) at Deoband, faced firm opposition on the question of politics from Muhammad Ahmad (the son of Nanautwi and father of Muhammad Tayyib, and chancellor of Deoband from 1894 to 1928); but Muhammad Ahmad seems to have retained a deep attachment to Mahmud al-Hasan, as indicated by him and his family going to meet al-Hasan upon his reaching Bombay after his imprisonment in Malta by the British for his revolutionary activities [Rizvi, History, 1:197]. Curious readers should also note that, in fact, Ahmad’s cooperation with the British led to them giving him the honorific title shams al-‘ulama (which he later returned) [see Gail Minault, The Khilafat Movement, p. 27; the website of Darul Uloom Waqf Deoband; Rizvi, History, 2:38]. Moreover, Muhammad Ahmad is said to have been behind the removal of Sindhi from Deoband; and he and his faction allegedly reported Sindhi to the British authorities for seditious behavior [see Hartung; Minault, Khilafat Movement, pp. 29 and 31]. Metcalf notes that “Deobandis seem to have had little hesitation about the legitimacy of taking government jobs [under the British],” and “they sustained a traditional Muslim strategy already current in India of tolerance of alien regimes” [Metcalf, Islamic Revival, p. 253].

“Madani himself only agreed to return to Deoband as principal, in 1927, when the seminary’s administration granted him permission to flout their policy of banning teachers from political agitation. ”Madani himself only agreed to return to Deoband as principal, in 1927, when the seminary’s administration granted him permission to flout their policy of banning teachers from political agitation. The administration perhaps accepted this stipulation because the institution was at a crisis point with disputes that led to the resignations of leading scholars like Anwar Shah Kashmiri and Shabbir Ahmad Usmani [see Syed Lubna Shireen’s doctoral dissertation, pp. 63 and 87–9; Khan Talat Sultana’s doctoral dissertation, pp. 38–9—the latter two PhDs being uncomfortably alike in parts; Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age: Religious Authority and Internal Criticism, p. 25; Rizvi, History, 1:209–213]. Yet Madani himself stressed the apolitical attitude of Deoband as an institution when it came under suspicion from the British (cited by Ingram on p. 49). Furthermore, Madani’s Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind immediately abandoned political activism after India gained independence from the British in 1947, and has since proudly declared its “secular” values [see Taberez Ahmed Neyazi, and the forthcoming publication of the Jamiat’s own history by Turath, UK].

Yet it seems—and this requires further research—that Thanawi’s political idealism flourishes over Madani-like pragmatism when Deobandis can operate in a Muslim-majority society. Ingram makes a number of references to the Taliban rulers of Afghanistan, who Moosa described as reflecting certain “pathologies” rather than the Deobandi “madrasa network” but which is still “a version of Deobandi theology on steroids” [Moosa, What is a Madrasa?], and is nonetheless “all Deobandi” [Zaman, Thanawi, p. 119]. Moreover, Zaman has demonstrated the significant political activism of Pakistani Deobandis, from Shabbir Ahmad Usmani until the present day, including the many clerics who belonged to the parliamentary opposition alliance MMA (Muttahida Majlis-i ‘Amal) and those who served on government projects, committees and worked with the government (such as Muhammad Shafi and his son Taqi Usmani, who served as an official judge) [see Rizvi, History, 2:70; Zaman, Chapter 3, Islam in Pakistan]. In addition, Ingram presents Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, the founder of the Awami League of Bangladeshi prominence, as a Deobandi political activist, on account of his studying in Deoband between 1907 and 1909 [p. 203]. However, even though his example would support a theory of a limited Deobandi activism in British India and then overt activism in a Muslim-majority country, the importance of Deobandi principles for him is still unclear, despite it being said that his time in Deoband and association and study with Mahmud al-Hasan and Madani led him to be “very much influenced by his [al-Hasan’s] ideology” [see Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses].

A Mistake

Of mistakes, only one stood out in this excellently composed work: the mistaken naming of Abul Kalam Azad as “Abdul Kalam Azad” [p. 191]. However, this is most probably a mere typographical error that was not picked up during the proofread, as opposed to a genuine mistake, because Ingram’s transcriptions and knowledge of the material is usually of the highest order. Furthermore, Ingram correctly spells Azad’s name in the original PhD thesis upon which this monograph is based [see Brannon D. Ingram, “Deobandis Abroad: Sufism, Ethics and Polemics in a Global Islamic Movement,” PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina, 2011, p. 35].

Conclusion

“Whilst Bano sees her own fieldwork and Razavian’s research as indicating “a shared level of rigidity in interpretation” between Deobandis in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, despite an apparent lack of interaction between them [Modern Islamic Authority, Volume 1, pp. 202–3], Ingram’s work on South Africa indicates that we must take local manifestations of Deobandism and their individuality seriously. “Whilst Bano sees her own fieldwork and Razavian’s research as indicating “a shared level of rigidity in interpretation” between Deobandis in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, despite an apparent lack of interaction between them [Modern Islamic Authority, Volume 1, pp. 202–3], Ingram’s work on South Africa indicates that we must take local manifestations of Deobandism and their individuality seriously. In addition, we should explore whether Deobandism should be further differentiated, certainly in political terms, primarily, depending on whether Deobandi communities find themselves as minorities or majorities (with the case of Bangladesh deserving more study in this regard, in comparison to Pakistan and Afghanistan). Towards this end, Ingram shows the importance of analyzing scholarly texts and personalities in such research. With the methodological addition of further ethnographic examination, we can see how analysis of Deobandis in Europe and North America, as well as the Indian subcontinent and Africa, can be profoundly refined, perhaps with a view to achieving future reform. Ingram has made a fine contribution to this project, and we welcome more works of this type by him and others.

Andrew Booso graduated in Law from the London School of Economics. He is on the Advisory Board of the Al-Salam Institute (Oxford and London, England), and coordinator for academic seminars at Islamic Courses, London. He has edited a number of translated texts associated with the Deoband movement by Ashraf Ali Thanawi, Husain Ahmad Madani, Abdullah Gangohi, Taqi Usmani, Salman Mansurpuri and the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind.