Some ten years ago, in the summer of 2009, I heard a striking phrase. At the end of a lengthy conversation, after a long pause, my informal teacher, named Bilal, said, “You know, I was freed by the revelation.”

Bilal was an older African-American gentleman. The revelation he referred to was the Qur’an. He uttered the phrase quietly – there was a mystery about the way he said it; being freed by the Qur’an was his miracle. When I heard it, I stayed quiet.

One must be careful with miracles. Too much explanation is likely to lead one astray. One can succumb, for example, to what Talal Asad, a cultural anthropologist, identifies in his recent book, Secular Translations, as the modern tendency of translating human experiences (and divine texts) into experiments, calculable representations of incalculable life. So how can one get a sense of what Bilal conveyed? How can a text free a person? As someone who dabbles in cultural anthropology with a focus on American Muslim experiences, I cannot leave this miracle unaddressed. What I have to offer, humbly, is a hunch and, hopefully, a useful term: Bilal’s freedom has something to do with the Qur’an’s sound, and cultural translation.

And What About Co-translators?

The word “translation” can mean many things. Most immediately, however, what comes to mind are objects: printed, physical or electronic renditions of foreign written texts. (While composing this piece, I conducted an experiment: I walked into a colleague’s office and asked, “What comes to your mind when you hear the word ‘translation’?” In a split-second, before saying a word, she glanced at a bookshelf; reflexively, she was looking for translations-as-objects.) The problem with the word “translation” is precisely this immediate resonance with works of translation that we, my contemporaries and I, have been conditioned to recognize robotically: written/printed texts that overlay other written/printed texts; objects on top of other objects.

“Much hides behind this reflex, including the contemporary, late modern common sense of what a text is, and a certainty we feel it is not. A text, we are conditioned to sense, is something written. Yet, what about spoken texts? (Or, if we listen to the Qur’an, what about the communicative signs in nature and within ourselves)? And what about human beings? “

Much hides behind this reflex, including the contemporary, late modern common sense of what a text is, and a certainty we feel it is not. A text, we are conditioned to sense, is something written. Yet, what about spoken texts? (Or, if we listen to the Qur’an, what about the communicative signs in nature and within ourselves)? And what about human beings? Hidden behind the perception of translations as objects are translators – how many of us can instantly recall the name of the person who translated our favorite foreign novel? Also concealed are audiences, human beings who carry on translations by responding to texts in their own, constantly changing, ways.

To make it even more messy (“natural” is a better word), translations-as-objects disguise translation as process. The objects we tend to think of as “translations” are tangible outcomes, visible markers of the processes through which perplexing texts are rendered into familiar terms. What makes it possible, what informs such processes and how they unfold, neither begins nor ends with an individual translator – or the calculable moments when she or he launches and completes a “translation project.” A broader grasp of it suggests that translation is a collective – and dialogical – endeavor. It involves translators and their audiences, with audiences serving as well-camouflaged co-translators.

What they work with is their shared language. And language, of course, is not an object. It is not a dictionary. A more resonant, while certainly imprecise, analogy for language is ecosystem. Translations, then, are ongoing processes that work within and between incessantly changing – and intertwined – linguistic ecosystems. To make this even less calculable, more ecosystem-like, what and how co-translators comprehend in a text – and, perhaps more importantly, what they feel it conveys and how it impacts them – is shaped by a countless number of influences. Some of such sways are specific to the environment a text’s co-translators share. Some, perhaps most, originate well before, and outside, their shared contexts.

A Kind of Blues

So, what did Bilal mean by “you know, I was freed by the revelation?” A key to an answer is in when and how he said it. He did not reveal it in our first meeting, the way one would show an identification card that states their official, state-given status. This revelation occurred naturally, after many conversations, once he sensed that I actually heard him, that his explanations and allusions made sense to me, his audience. Crucially, it happened when he likely recognized that I could, by that point, appreciate what the inflections of his voice might echo.

“Did I mention that Bilal was one of my informal teachers? What he prompted me to learn is a deeper, more careful appreciation of sound. The immediate subject of many of our conversations was the oral tafsir, spoken explanations of the Qur’anic signs, of his teacher, Imam Warith Deen Mohammed (1933-2008), a particularly impactful African-American Muslim authority.“

He knew, for example, that I recognized that his use of the word “freedom” was his translation, for me as non-African-American, of the African-American term “redemption.” He sensed, in part because we discussed it often, that I appreciated that the African-American, including Muslim, experiences that have been breathing life into the word “redemption” are not what one would likely find in a standard English dictionary – the closest word to it is the one he chose, “freedom.”

Did I mention that Bilal was one of my informal teachers? What he prompted me to learn is a deeper, more careful appreciation of sound. The immediate subject of many of our conversations was the oral tafsir, spoken explanations of the Qur’anic signs, of his teacher, Imam Warith Deen Mohammed (1933-2008), a particularly impactful African-American Muslim authority. Our conversations would often take place after I had done my homework, after I had listened to a selection of recorded speeches by Imam Mohammed, delivered in the 1970s, 80s, 90s, and 2000s. I would ask Bilal about some contextual details in the speeches, often related to some tangible events and dates. And he kept directing me to their sounds.

In part because of who Bilal was, he kept making references to jazz, blues and R&B, prompting me to hear resonant notes in Imam Mohammed’s tafsir. (His allusions were not unique. Many of my other interlocutors from the community, those of the same generation as Bilal, made similar musical references. A person of a different generation would likely nod toward distinct, but related, resonances). Because of Bilal, I came to appreciate, for instance, Bill Withers, and just how much the sound of Imam Mohammed’s most poignant notes resonated with, and was part of, the cultural ecosystem – a better phrase would be “a living universe” – inhabited in Withers’ songs. (In my classes and lectures, I often introduce an audio recording of an Imam Mohammed speech by first playing for my students Withers’ “Grandma’s Hands.” It helps to tune their hearing.)

Bilal’s sound interventions led me to appreciate the always-present kind-of-sadness, the blues, in Imam Mohammed’s voice. One can hear it – if they listen to his speeches – in his two stock phrases, his customary key notes, “always a few” and “that’s too bad.” “I’m convinced,” he said, for example, in his 2003 speech at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, “that leaders in the history of African-American people who are Christian, and that is a great majority, they got help from God and God has been in that work and God has been with us as long as we were with God…He is still with us. Few of us. And that’s too bad. But don’t feel discouraged because never in the history of a people there were many leading them. Always a few. Always a few.”

The sound of that “always a few” was Imam Mohammed’s blues – I say “blues,” because it is not really sad or sorrowful; there is incalculable depth to it, which includes joy (and humor) and promise and freedom. That underlying tone is very much part of his sound, a sound of his people, including Bilal. And it is also very much Qur’anic. A prevalent sound, a key emotional movement of the Qur’an when it is soundly recited is that of huzn– a kind of sorrow, a kind of blues.

“The sound of that ‘always a few’ was Imam Mohammed’s blues – I say ‘blues,’ because it is not really sad or sorrowful; there is incalculable depth to it, which includes joy (and humor) and promise and freedom. That underlying tone is very much part of his sound, a sound of his people, including Bilal. And it is also very much Qur’anic.”

“The Movement of Scripture”

Key to understanding Bilal’s “you know, I was freed by the revelation” was that phrase’s sound – and its movement. His “you know” solicited active hearing, an act of humble submission. It was an invitation to lend an ear, to move toward what Bilal was about to convey. The cadence of that phrase was slow and contemplative. It echoed twists and turns of his eventful life – a stream within a larger community, a deeper history. And it was respectful of the unknowable, including for him, in what he was about to say.

“Key to understanding Bilal’s ‘you know, I was freed by the revelation’ was that phrase’s sound – and its movement. His ‘you know’ solicited active hearing, an act of humble submission.“

Bilal’s sound, the audible movement of his expression, suggested that his freedom was not a once-off temporal marker but a life-long process. It is how he came to live his life – striving to be mindful of deeper realities, divine and human, in each of life’s tangible and intangible twists. That phrase expressed Bilal’s part, as an interlocutor and co-translator, in his teacher’s and many other African-American Muslims’ endeavor of translating the Qur’an into an African-American revelation, of breathing – re-sounding– the Qur’an into their lives. It signaled that he was (striving to keep up with being ) attuned to what Imam Mohammed called “the movement of scripture.”

A (Sound) Hunch

“Related to this is perhaps the toughest conundrum: What about the agency of the text itself? Or, to repeat my opening question: How can a text, in this case the Qur’an, free a person?”A cultural translation is a translation of a text into life. It simply cannot happen without co-translators. Related to this is perhaps the toughest conundrum: What about the agency of the text itself? Or, to repeat my opening question: How can a text, in this case the Qur’an, free a person? An answer, I think, must begin with an acknowledgement of one’s limitations: one cannot measure and convey precisely what such a process entails (we are dealing here with deep, multidimensional and dynamic realities). A good answer is a sound hunch. My hunch, in the case of Bilal and the Qur’an, is that the Qur’an’s sound – its blues – is key to how it has freed Bilal (with the help from Bilal, his family, Imam Mohammed and many other of the revelation’s co-translators, including, as Imam Mohammed emphasized in the speech I quoted, “leaders in the history of African-American people who are Christian”).

Of course, sound is movement. The Qur’an’s cultural co-translators include, it is useful to highlight, sign language translators, human beings who translate it through careful, embodied movements – as well as other ordinary people who keep translating the revelation into how they live their lives. What matters for those who would like to come up with sound hunches about cultural translations is the discipline of striving to appreciate just how multidimensional they are. What matters is an appreciation of texts’ co-translators.

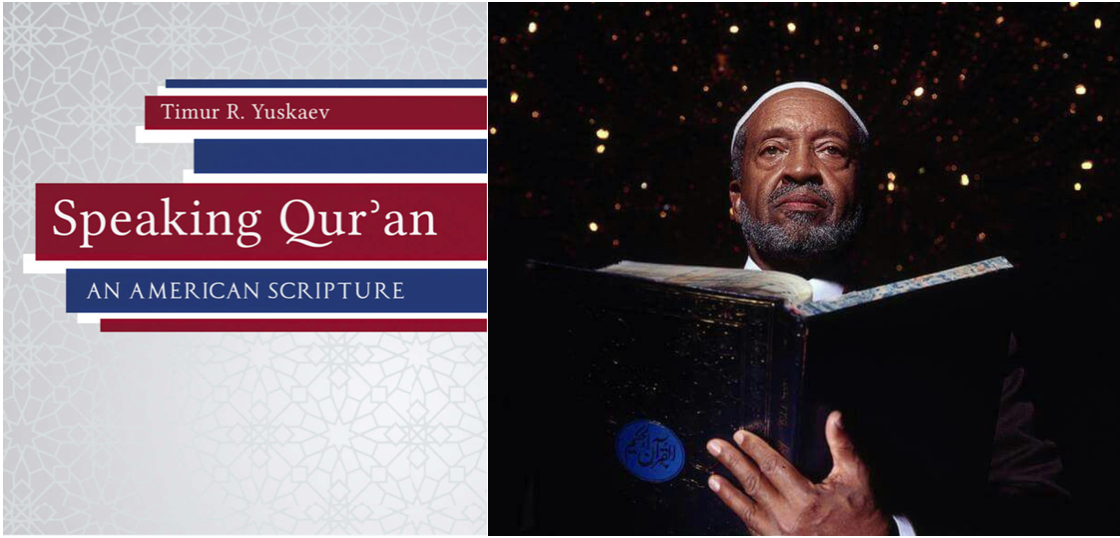

Timur Yuskaev is Associate Professor of Contemporary Islam at Hartford Seminary, where he co-edits the Muslim World journal and directs programs training American Muslim religious professionals, chaplains and imams. He holds a PhD in Religious Studies with specialization in Islamic Studies and American Religions from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His Speaking Qur’an: An American Scripture (University of South Carolina Press, 2017) examines American Muslim cultural translations of the Qur’an.