In the first part of the twentieth century, Muslims in the monarchical state of Kedah, Malaysia used to give zakat through long-standing informal patterns that supported community and religious life. Known as the “rice bowl” of Malaysia, Kedah’s productive paddy fields enabled rice farmers to consistently exceed the minimum threshold of zakat (nisab) and to give a share of their harvest to religious teachers, mosque caretakers, and those in their villages they knew to be hungry and vulnerable. Harvest was a time that linked the labor of agriculture, the nurturing of Islamic tradition, and the tending of everyday connections – a time of integrated cultivation of biological, spiritual, and human life in a local world. The implementation in 1955 of a formal bureaucracy to collect zakat changed those patterns and changed the way that people in Kedah lived Islam. A statewide ordinance centralized collection under a new Zakat Office, which was administered by a local official (amil) on behalf of the sultan.[1] In subsequent decades, this new zakat bureaucracy came to be seen as unfair and burdensome by Kedah rice farmers.[2] They missed the freedom they used to have to decide how to give their zakat.[3]

“By the time political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott arrived in Kedah in the late 1970s to conduct field research on peasant life, villagers had developed a bifurcated understanding of zakat, which they identified through two distinct and contrasting categories.”

By the time political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott arrived in Kedah in the late 1970s to conduct field research on peasant life, villagers had developed a bifurcated understanding of zakat, which they identified through two distinct and contrasting categories. Rice farmers called the formal, bureaucratically-collected zakat zakat raja, “the ruler’s zakat” or “the government’s zakat,” and they described the zakat that they themselves freely gave to others as zakatperibadi, or “personal zakat.”[4] Scott chronicled the multiple techniques that villagers used to evade paying zakat raja, including understating their cultivated acreage and giving less than the stated amount owed to the amil (open fraud).[5] Paddy farmers invested in a “silent struggle” to “[tear] down the edifice of the official zakat,” Scott notes, because they thought it was inequitably assessed on those who worked the land and not landowners, they did not see it help local people, and they assumed the collectors were corrupt.[6] They did not, however, stop giving zakat. Instead, they conceptualized a new modality of zakat that would enable them to care for others in their local community. Zakat peribadiwas a practice of zakat they defined in terms of personhood, the self that plays out social roles as part of a collectivity.

“The case of the evasion and fulfillment of zakat in Kedah provides an intriguing picture of how Muslims who are committed to living within the bounds of sharia can push back against sharia regimes they determine to be less-than-legitimate or outright corrupt.”

The case of the evasion and fulfillment of zakat in Kedah provides an intriguing picture of how Muslims who are committed to living within the bounds of sharia can push back against sharia regimes they determine to be less-than-legitimate or outright corrupt. Faced with forced compliance, Muslim farmers found a way to demarcate an unforced and more satisfying way to fulfill their Islamic obligation to give to those in need. They worked with what they knew to be the totality of God’s will for humanity in order to work around a particular imposition of Islam by the state. The religious imagination we see in their creative re-framing of zakat suggests an expansive and confident understanding of sharia: they claimed the zakat practice they themselves defined as the legitimately Islamic one.

Reconfiguring Zakat in Contemporary Islam

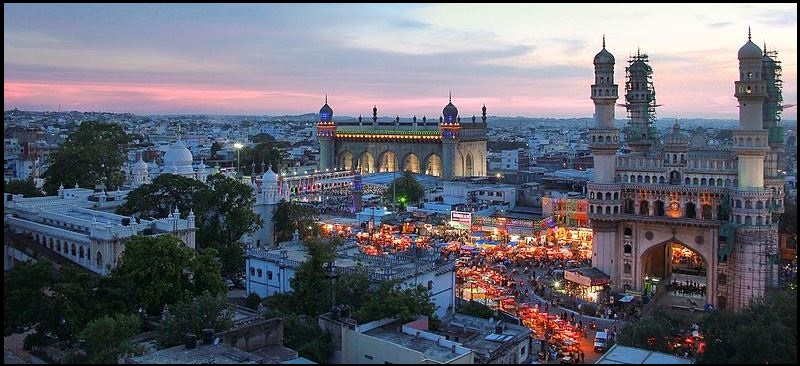

Zakat constitutes a site of social and religious creativity in contemporary Islam, as the Kedah case shows. In the modern period, zakat occasions a discourse about how best to live morally in a world complicated by dangerous imbalances of power. It has been embraced by those who “[seek] an idiom of transformation” for projects of social reform.[7] Like Muslims in Kedah, Muslims in Hyderabad, India have also defined a new mode of giving zakat to care for the vulnerable. The following description of the Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust in India traces how one zakat project shifted from giving to the poor to attempting to address the structures of poverty itself.

“The following description of the Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust in India traces how one zakat project shifted from giving to the poor to attempting to address the structures of poverty itself.”These new configurations of zakat reflect the way that Islamic tradition changes over time, and becomes embedded in shifting social, cultural, political, and temporal contexts. In the past, poverty was a condition to be endured. In modernity, poverty stands as a social problem to be solved.[8] As an obligatory redistributive transfer, zakat structures interdependence among Muslims, as it has since the formation of Islam. Both the giver and the receiver are necessary to fulfill the obligation to give and thereby purify one’s remaining wealth, according to the traditional Islamic understanding of zakat. In the contemporary period, zakat has been elaborated beyond material transfer into affective and political projects of care, humanitarian aid, and social justice. It has been re-positioned as the ground for complex assemblages that aspire to bring into being new forms of moral obligation, wellbeing, equity, subjectivity, devotion, and belonging.

In the efforts of the Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust, zakat emerges as an experimental site for reforming gender and poverty by instigating a countercultural resistance to dowry. Donors to the Trust chose to focus on dowry as a critical juncture for disrupting cycles of poverty. Their efforts disclose how zakat can be understood as a practical theodicy, a vehicle for shaping practical efforts to limit precarity and to reject human disposability. Judith Butler (2009) defines precarity as:

That politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks of support and become differentially exposed to injury, violence, and death. Such populations are at heightened risk of disease, poverty, starvation, displacement, and of exposure to violence without protection. Precarity also characterizes that politically induced condition of maximum vulnerability for populations exposed to arbitrary state violence and to other forms of aggression that are not enacted by states and against which states do not offer adequate protection.[9]

Butler’s definition of precarity emphasizes its political nature. It is a condition of vulnerability and exposure to injury and violence that is neither natural nor inevitable, but rather results from policy and social failure. This case study of zakat among Muslims in India follows Butler by situating precarity within the social field—the domain in which the structures of precarity take root, and the domain in which the transformation of those structures becomes possible.

“In the efforts of the Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust, zakat emerges as an experimental site for reforming gender and poverty by instigating a countercultural resistance to dowry.”Exploring how Muslims draw on the practice of zakat to build out new socio-religious projects to counter precarity allows us to see zakat as a practical theodicy. Philosopher Kenneth Surin (2004) offers a helpful definition of practical theodicy. He states that if we “evacuate theodicy from the realm of theory in order to relocate it in the realm of practice,” we can “abandon a purely theoretical or ‘aesthetic’ approach to the ‘problem of evil,’ and instead [view] it as an essentially practical problem.”[10] This approach shifts away from theological explanations in order to explore how people “answer the practical questions: What does Goddo to overcome the evil and suffering that exist in his creation? What do we (qua creatures of God) do to overcome evil and suffering?”[11] Everyday attempts to “interrupt” what Surin calls “humankind’s continuity-in-evil” thus constitute a practical theodicy that grounds people and gives them traction to respond to human suffering.[12]

Zakat and the Geography of Violence in India

The Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust was formed in the aftermath of violent communal riots between Muslims and Hindus following the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. Across India, communal riots flared in many cities, including the historic area of the Old City of Hyderabad. For more than six months, clashes erupted between Muslims and Hindus while police tried to contain the violence by enforcing a public curfew. These riots marked a crisis that was both local and national, as many people linked the harm and injury they witnessed in their city to a larger scale of suffering and a pervasive climate of fear across the country. The violence of the riots in Hyderabad destabilized a sense of the city as shielded by its own traditions of cosmopolitanism. Metropolitan Hyderabad, with its population of nine million people, is a historically multi-religious city, yet many experienced the riots as a turning point in which local multiculturalism was subsumed by a dangerous politics of communal polarization. The subsequent electoral successes of Hindu nationalist groups that sought to “purify” India of its religious minorities further confirmed for many Muslims the sense of a changed and charged political climate. The Babri Masjid riots came to be seen by Indian Muslims as a turning point after which their local security and national integration could no longer be taken for granted.

“The Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust was formed in the aftermath of violent communal riots between Muslims and Hindus following the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. Across India, communal riots flared in many cities, including the historic area of the Old City of Hyderabad. “

Within Hyderabad, there were many efforts to respond to the damage caused by communal violence in the Old City. A small group of Sunni families who wanted to help local victims of the riots pooled their zakat and formed the Hyderabad Zakat and Charitable Trust. In the initial years after the riots, the Zakat Trust focused on Muslim slum areas of the Old City. They rooted their projects in the city’s landscape of trauma. They opened healthcare clinics, started income-generating workshops, and founded schools. After more than a decade of running such projects, the donors of the Trust decided to shift the majority of their zakat into the field of higher education, offering scholarships to college and university students.

In order to distribute their zakat as scholarships, the Trust holds scholarship camps for potential recipients. As part of the process of receiving a zakat-funded scholarship, students sign a formal oath that shapes a trajectory of moral action and gender reform. In the first part of the oath, all students vow to give back the same amount of money that the Trust gave them, once they secure gainful employment. In the second part of the oath, students refuse to give or take a dowry. Linking zakat to the refusal of dowry explicitly introduces a critique of prevailing gender constructions into zakat. According to Islamic tradition, a bride is to receive a mahr, a capital gift that becomes her personal property in the course of marriage.[13] In India, and across South Asia, the popular practice of dowry works in the reverse: the young woman’s family pays a sum—in cash or in kind—to the groom’s family. The current economic situation has brought about increased pressure to raise larger dowries, which has resulted in a large number of young women in India’s Muslim communities who struggle to put together a sufficient dowry to marry. Sociologists have noted the entrenched practice of dowry across caste, class, and religious groups in India,[14] despite the passage in 1961 of national legislation prohibiting dowry.[15] The Trust draws on a broader social critique of dowry, yet locates the countercultural resistance to dowry within a specifically Islamic social ethic that integrates gender reform into collective wellbeing.

“In order to distribute their zakat as scholarships, the Trust holds scholarship camps for potential recipients. As part of the process of receiving a zakat-funded scholarship, students sign a formal oath that shapes a trajectory of moral action and gender reform.”

In shifting their distribution to scholarships, the Zakat Trust is responding to a context of increasing poverty, educational deprivation, and inequality. In 2006, the Indian government released the Sachar Committee Report, which notes that the “expansion of educational opportunities since Independence has not led to a convergence of attainment levels between Muslims and ‘All Others.’ Rather, the initial disparities between Muslims and ‘All Others’ have widened.”[16] Muslims, to put it directly, have become India’s new ‘untouchables.’ Across India, Muslim students have lower levels of educational attainment, but Muslim girls especially so. In the state of Andhra Pradesh, most Muslim girls are first-generation learners. A 2005 study of Hyderabad showed that only 34% finish primary school; and less than 15% complete high school through grade ten.[17] While all poorer students in India suffer from the limitations of national and state governments to guarantee universal primary education, girls can face additional sociocultural barriers to education, including the practice of restricting girls past puberty from attending school by justifying it as an Islamic practice of gender seclusion (purdah). Dowry reinforces gender discrimination in Muslim communities as families muster limited financial resources to pay for a young woman’s dowry, thereby closing the door on funding her education. This, in turn, reinforces low educational attainment and further entrenches poverty. By presenting a critique of gender bias through the pledge to reform dowry and by giving scholarships, the Trust wants to eliminate any justification for the exclusion or repression of girls from education in the name of Islam.

Among the different practices of zakat in India, the Trust is innovative in terms of using an oath in the distribution of zakat. According to Islamic tradition, zakat is to be given unconditionally if it is to be considered legitimate, yet donors to the Trust feel they must take this step in order to break interlocking cycles of poverty and gender bias. The donor who authored the oath, Hussain, shared with me the internal conflicts he has about asking the students to take it: “I know this could make our zakat impure, you know. I know that. But we have to do it. We have them there, we have this opportunity. The stakes are too high—we have to say something.” As a religious practice, zakat has its sanctioned interpretations, but as far as Hussain is concerned, the Trust must be creative in the face of moral demands for change. Challenging practices like dowry, which are both cultural and material, means confronting what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (2000) calls “the extraordinary inertia which results in the inscription of social structures in bodies.”[18] When shaping a new practice of zakat produces an inner conflict of conscience, Hussain and other volunteers state that they must rely on God’s forgiveness. Placing their zakat practice between the contingencies of the local situation and God’s mercy generates a hermeneutic of necessity that supersedes practices of the past. Like the Kedah case, this practice of zakat constitutes a space for reflecting on and creatively reconfiguring the affordances of Islamic law.

Zakat as Practical Theodicy

Through the oath against dowry and the pledge of future donation, the Trust attempts to activate an Islamic ethical disposition that anchors students in a sense that the world contains the possibility of change, that deprivation and injustice are not inevitable. The Trust wants to give students what anthropologist Michael D. Jackson (2011) calls “existential power”—the “sense that one is able to act on the situation that is acting on you,” which is “contingent on our relationship with others.”[19] The Trust shapes this existential power contextually, in concentric circles that move outward from the individual, into the family, and then into society, implicitly recognizing how the ethical self, in the words of anthropologist Talal Asad (2015), “overlaps with, and contains other selves.”[20] The Trust thus makes the effort to counter the gendered structures of poverty into a way of opening up the imagination of what it means to be Muslim, while also inscribing both donor and recipient in a common moral project in which individual action brings about collective wellbeing.

“Through the oath against dowry and the pledge of future donation, the Trust attempts to activate an Islamic ethical disposition that anchors students in a sense that the world contains the possibility of change, that deprivation and injustice are not inevitable”

The Trust’s practice is an experimental one, shaping new moral subjectivities through the distribution of zakat. Behind the Trust’s public confidence in transformative ethical action, the experiential dimension of this zakat practice is complex and somewhat ambiguous. In structured interviews, donors reveal a sense of doubt about the efficacy of the project, and point to an uncertainty that subtends this experimental zakat practice. A pained awareness of the limited efficacy of such efforts exists alongside a clear promise of transformation. Donors’ reflections on zakat thus emphasize the crystallization of existential power and also its elusiveness. They endure rather than resolve the moral complications of their zakat practice in order to redress poverty and gender discrimination. Donors are, in the words of ethicist Willis Jenkins (2013), “inventing new possibilities of cultural action from their inheritances,” in the hopes of making themselves and the recipients of zakat “competent to the problems they face.”[21] The challenges, both theological and practical, of their experimental project are absorbed by the deep moral rejection of precarity. Hussain, the author of the oath, explained at length the urgent stakes of this rejection:

Yes, people give dowry, they accept it. But what to do? We cannot accept it. Nobody will tell you this, but I am telling you this. Do you know how slavery is practiced in India because of dowry? Do you know how it functions? Like this: I have a daughter to be married. I go to the moneylender. I don’t have anything to mortgage, so I mortgage my son. For how much? You know? About 6000 rupees.

So what happens is, I take 6000 rupees and come back. My son starts to go to this moneylender every single morning and starts to work for him. Right from sweeping his floor, to washing his clothes, everything. He works like a slave. His salary is fixed, say at 200 rupees per month. The 6000 rupees which is given as a loan—this 200 rupees which is the salary is deducted by the moneylender as the interest on that loan, payment for food or whatever.

So this guy is mortgaged for life. After one year, my second daughter is to be married, so I take my second son and mortgage him. After another year, my third daughter is to be married and I don’t have any sons, so I go to a different moneylender and I mortgage myself. I work. I have nothing to eat because my salary goes towards paying off the loan. I’m not earning anything, the whole day I work. This goes on, this is a practice.

This is slavery. This happens here in India today. I will take you with me and show you. Not far from here, there is a village. I went to build a building near there last month. I can bring you to people who are in this slavery so you can talk to them. Do you want to write a paper on it? I can show you. This is another facet of the dowry system. These are unimaginable things that happen. This is a normal phenomenon. This is the social evil.

In this analysis, Hussain sought to make explicit how the gendered cultural expectations of dowry connect to the enslavement of debt bondage. When such extreme forms of exploitation shift from the “unimaginable” to become “normal,” that is “evil.” While the Trust explicitly addresses gender discrimination through dowry, its connection to other instruments of oppression remains unspoken. Hussain’s words affirm that rejecting one manifestation of precarity—dowry—helps break down a more pervasive and ensnaring web of disposability. In explicating this submerged danger of precarity, Hussain temporarily and imaginatively inhabits the position of the father in order to tease out the interlocking cycles of debt that can cumulatively ambush an entire family. “This is how I am connected to myself, to my religion, by putting myself in that situation,” he added. “We are all connected to the Creator by the person we are, by the thoughts we have in our minds. I think of what I can do and I have to try.” His words mark both the ethical mandate—the “have to”—and the imperfect, experimental nature of the effort—the “try.” The ethos of zakat, according to Hussain, is to mark the refusal to let evil be normal, and to reject that precarity that effectively ends human life by assigning disposability.

The Trust’s practice of zakat to reform gender and poverty accommodates a wide range of experience, both poetic transformations of consciousness and aporetic moments of sedimented despair. This attests to the exploratory nature of the Trust’s project: donors are building a model as they go for navigating the transformation of poverty in the intersection of tradition, culture, gender, self, other, nation, and God. For donors of the Trust, their actions to instigate a new form of Islamic gender ethics as a way of confronting poverty are not just their own. Surin’s questions about practical theodicy—What does Goddo to overcome the evil and suffering that exist in his creation? What do we (qua creatures of God) do to overcome evil and suffering?—indicate two separate modes of action, human and divine. Zakat donors who formed the Trust understand themselves as actors in a shared human world, but they also understand their actions to be connected to a divine, transcendent reality. Human action and divine action remain identifiably different in nature, yet donors express the sense that they are connected. We see in their narratives a religious understanding of existential power.

“The Trust’s practice of zakat to reform gender and poverty accommodates a wide range of experience, both poetic transformations of consciousness and aporetic moments of sedimented despair. This attests to the exploratory nature of the Trust’s project: donors are building a model as they go for navigating the transformation of poverty in the intersection of tradition, culture, gender, self, other, nation, and God. “

The practice of zakat is both obligatory and open, allowing it to reflect distinct contextual realities and to bear a unique ethos in particular places. In the contemporary context of Malaysia, Scott relates that villagers who evaded paying the official zakat did so without voicing a critique of governmentality, thus their resistance remained “offstage.”[22] For Muslims who give their zakat through the Trust, in contrast to Kedah farmers, the occasion to centralize critique and reconfigure human relationships is part of what makes zakat moral. Muslims in India today occupy a position of entrenched subalternity in the context of Hindutva, the ideology of religious nationalism that defines India in the exclusive terms of caste Hinduism. They live as a fugitive public in the shadows of a state that fails to protect them. Notions of purification may characterize some zakat practices, but the sense of completion and epistemological clarity implied by the process of purification eludes donors who shape the Trust. For them, zakat becomes an opportunity to experiment with countering vulnerability, disposability, and precarity—realities that have no place in their imagination of an Islamic social order. Understood in Islamic tradition as an act of piety, zakat purifies wealth. When seen in light of the contemporary struggle to transform Muslim poverty in India, perhaps that pious purification can now also be seen in removing and rupturing behavioral despair.

*Danielle Widmann Abraham is Assistant Professor of Islamic Studies and Comparative Religion at Ursinus College, where she also holds the Walter Livingston Wright Professorship in Middle East Studies.

[1]Scott, J. (1987). Resistance without protest and without organization: Peasant opposition to the Islamic zakat and Christian tithe. Comparative Studies in Society and History,29(3), p.425.

[2]Ibid, p.426.

[3]Ibid, p.431.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Ibid, p.429

[6]Ibid, p.432.

[7]Liu, M. (2012). Under Solomon’s throne: Uzbek visions of renewal in Osh. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, p.152.

[8]Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p.22.

[9]Butler, J. (2009). Performativity, precarity, and sexual politics. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, 4(3), p.ii.

[10]Surin, K. (2004). Theology and the problem of evil. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, p.67.

[11]Ibid.

[12]Ibid, p.159.

[13]Ali, K. (2010). Marriage and slavery in early Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p.54.

[14]Srinivas, M. (1978). The changing position of Indian women. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[15]India Ministry of Law. (1961). The Dowry Prohibition Act 1961. Delhi, India: Universal Law Publishing.

[16]Prime Minister’s High Level Committee. (2006). Social, economic, and educational status of the Muslim community of India.(Cabinet Secretariat) New Delhi, India: Government of India, p.81.

[17]Hasan, Z., & Menon, R. (2005). Educating Muslim girls: A comparison of five Indian cities. New Delhi, India: Women Unlimited/Kali for Women, p.107.

[18]Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian meditations. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p.172.

[19]Jackson, M. (2011). Life within limits: Well-Being in a world of want. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp.156, 195.

[20]Asad, T. (2015). Thinking about tradition, religion, and politics in Egypt today. Critical Inquiry, 42(11), p.175.

[21]Jenkins, W. (2013). The future of ethics: Sustainability, social justice, and religious creativity. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, p.6.

[22]Scott, p.434.