1- Introduction

Hostility towards Muslim Americans is arguably a foregone conclusion. Ample evidence demonstrates that negative attitudes towards U.S. Muslims are pervasive among the mass public (Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner, 2009; Panagopoulos, 2006; Sides and Gross, 2013), are rooted in old-fashioned racist beliefs (Lajevardi and Oskooii, 2018), and and played an important role in shaping Trump support in the 2016 election (Lajevardi and Abrajano, 2019). In recent years, sociopolitical backlash against Muslim Americans has manifested beyond negative attitudes. For example, 2017 saw 14 states introduce anti-Sharia law bills, with Texas and Arkansas enacting the legislation.[1] Concurrently, the number of anti- Muslim hate groups rose for the third straight year—from 101 chapters to 114 in 2017— coinciding with Trump’s campaign and presidency.[2] While Donald Trump implemented three versions of a travel ban targeting citizens from Muslim majority countries, often referred to as the “Muslim Ban” (Collingwood, Lajevardi and Oskooii, 2018), the Council on American Islamic Relations recorded 2,599 anti-Muslim bias incidents taking place across the nation that year (CAIR, 2018).

“I rely on the news media as a vital lens in assessing how Muslims and Muslim Americans have been portrayed to the mass public over a period of 25 years in the decade before and in the near decade and a half after. In this vein, I examine the volume and the sentiment of their coverage compared to other groups that scholars have regularly demonstrated are framed negatively.”

Notwithstanding the scholarly work that demonstrates the low situation of Muslims in the American sociopolitical context, it is difficult to build a temporal landscape of the treatment of Muslim Americans relative to other marginalized communities in the United States without data spanning many years. Very little public opinion data exists on attitudes towards Muslims and Muslim Americans before 9/11. As such, scholarly endeavors aiming to measure how Muslim Americans were communicated to the public prior to 9/11 are further complicated by data unavailability.

I rely on the news media as a vital lens in assessing how Muslims and Muslim Americans have been portrayed to the mass public over a period of 25 years in the decade before and in the near decade and a half after. In this vein, I examine the volume and the sentiment of their coverage compared to other groups that scholars have regularly demonstrated are framed negatively.

In what follows, I briefly outline the role of the news media, discuss what news broad-casts can reveal to us about how groups broadly may be processed by the public. Next, I provide a descriptive accounting of the sentiment and volume of news coverage of Muslims and Muslim Americans compared to other marginalized groups over time. Finally, I conclude with several takeaways and conclusions.

2- The Role of the News Media

“Yet, the news media is neither neutral nor value-free. The media sustains stereotypes, such as associating welfare with ‘undeserving blacks’…“The news media is an important conduit for conveying messages to the public (Chomsky, 1997; Markham and Maslog, 1971). It shapes attitudes, influences the national discourse, and generates stereotypes (Brummett, 2014). Yet, the news media is neither neutral nor value-free. The media sustains stereotypes, such as associating welfare with “undeserving blacks” (Gilens, 1999) and social security with whites (Winter, 2006, 2008), and has an enormous impact on the development of racial attitudes (Entman and Rojecki, 2001; Kellstedt, 2000). Past research suggests that the ways in which outgroups are represented in media impacts the public’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors towards members of those outgroups (Harwood et al., 2012; Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan, 2016; Mastro, 2009; Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes, 2013; Saleem, Yang and Ramasubramanian, 2016), and shapes support for policies that harm members of the depicted outgroup (Mastro and Kopacz, 2006; Ramasubramanian, 2011; Tan, Fujioka and Tan, 2000).

Given that Arabs, Middle Easterners, and foreign Muslims are frequently linked with tropes of violence, terrorism, and aggression across American media outlets (Alsultany, 2012; Nacos, 2016; Nacos and Torres-Reyna, 2002, 2007), I expect these findings to extend to American Muslims as well. Indeed, prior research has found that reliance on the media for information about Muslims, rather than on direct contact with them, was positively associated with negative emotions, stereotypic beliefs, and support for harmful policies (Saleem, Yang and Ramasubramanian, 2016).

3- Method

In my research, I focus specifically on how the news media discusses Muslims (the foreign group) and Muslim Americans (the domestic group). For baseline comparisons, I compare their coverage to that of three other marginalized groups in America: Asian Americans, African Americans, and Latinos.

“In my research, I focus specifically on how the news media discusses Muslims (the foreign group) and Muslim Americans (the domestic group). For baseline comparisons, I compare their coverage to that of three other marginalized groups in America: Asian Americans, African Americans, and Latinos.”

I collected the text of all available broadcast news transcripts from CNN, FOX, and MSNBC from 1992-2015 through a platform called Lexis Nexis Academic. One limitation is that only CNN broadcasts are available from 1992-1997. In 1998, Fox News broadcasts become available, and in 1999, MSNBC becomes available as well. My Lexis Nexis search results yielded 843,906 transcripts: 718,388 of which came from CNN; 101,871 from Fox; and 23,647 from MSNBC. Overall, 85.12% of the dataset came from CNN, 12.07% came from Fox, and 2.8% came from MSNBC. From there, I removed all observations that were not in fact broadcast transcripts, but were rather online articles from the outlets. For example, I removed articles from CNN.com, FOX.com, and MSNBC.com. This yielded a total of 588,507 broadcasts: 459,628 from CNN, 104,129 from FOX, and 24,749 from MSNBC.

Once I compiled all of the text files, I conducted a textual analysis method called “sentiment analysis” on all of the transcripts. Sentiment analysis empirically determines the tone of a text by examining incidences of positive and negative words in set of documents (Bhonde et al., 2015). Each word in a broadcast is assigned a neutral (e.g., 0), positive, or negative value. At the end of this analysis, each broadcast is assigned a “sentiment” value which takes the sum of value assigned to each word in the broadcast. I call this the “raw sentiment score.” For ease of interpretation, I standardize this score.

Since I am interested in (1) the volume of coverage of Muslims and Muslim Americans and (2) the sentiment of coverage of Muslims and Muslim Americans compared to other marginalized groups, I subsetted the data into separate datasets for each group I was interested in examining: Muslims, Muslim Americans, Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans.

4- How the News Media Depicts Muslims Foreign and Domestic Over Time

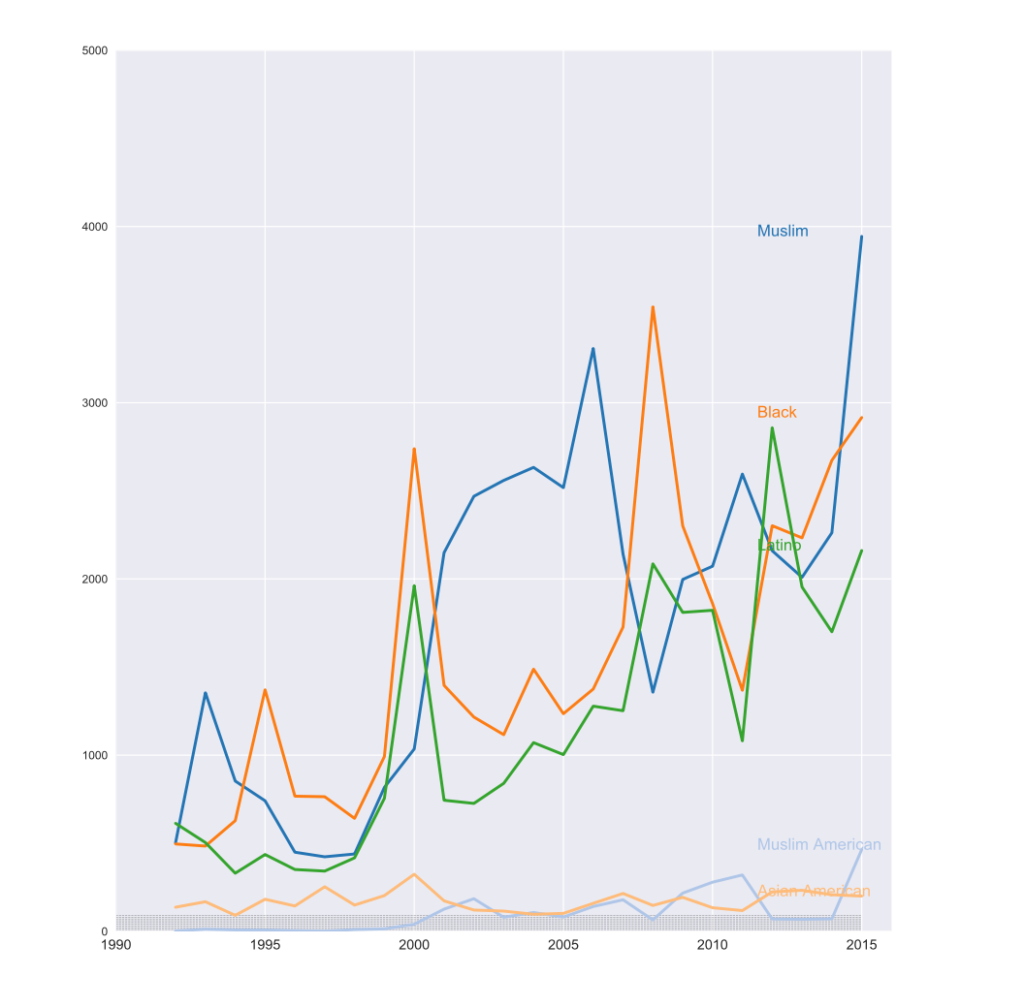

First, I examine changes in the volume of media coverage for each of the examined groups. I find that the volume of coverage of Muslim Americans, but more so Muslims (the foreign group), has increased markedly over time. Figure 1 shows the volume of coverage each year for each racial group and demonstrates an increase in the aggregate coverage of Muslim Americans by year and over time from 1992 and 2015. Even more impressive is the increase in coverage of Muslims; in the aftermath of 9/11, Muslims have increasingly dominated American news broadcasts more than any other evaluated group.

“Muslims have experienced the greatest increases in coverage relative to Blacks and Latinos. In 2000, the year prior to 9/11, Muslims, Blacks, and Latinos appear in 1.79%, 4.61%, and 3.27% of all available news media broadcasts, respectively… In 2015, I find that Muslims turn up in 26.50% of all available broadcasts, compared to 18.83% and 13.91% for mentions of Blacks and Latinos, respectively “

Muslims have experienced the greatest increases in coverage relative to Blacks and Latinos. In 2000, the year prior to 9/11, Muslims, Blacks, and Latinos appear in 1.79%, 4.61%, and 3.27% of all available news media broadcasts, respectively. Specifically, Muslims appeared in 993 transcripts, Blacks in 2,554 transcripts, and Latinos in 1,809 transcripts. There was a total of 55,295 transcripts in the full corpus in the year 2000. However, these proportions changed drastically fifteen years later. In 2015, I find that Muslims turn up in 26.50% of all available broadcasts, compared to 18.83% and 13.91% for mentions of Blacks and Latinos, respectively. There were 14,465 available news broad- casts in 2015. Of those, 3,834 mentioned Muslims and were thus part of the Muslim corpus, 2,725 mentioned African Americans and were thus part of the Black corpus, and 2,012 mentioned Latinos and were part of the Latino corpus. In 2015, then, the news media covered Muslims almost twice as often as Latinos and almost 1.5 times more than Blacks, the two largest marginalized groups in America.

Figure 1: Changes in Volume of Group Mentions in the News Media Over Time

Next, I turn to the sentiment of media coverage of each group over time. Figure 2 displays the mean standardized sentiment score for each examined group by year, from 1992-2015. There are three important points to take away from this figure. First, mean Black, Latino, and Asian American sentiment trace each other over time, confirming the extant literature’s findings that these groups are often portrayed similarly and negatively. Second, mean sentiment for the foreign group – “Muslim” – falls consistently below that of Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans over time. This finding may be intuitive, however, given that Muslims are a foreign group compared to the rest of the examined groups, which are domestic groups. Perhaps the media simply portrays foreign groups differently than its domestic groups. This finding also makes sense in light of the fact that scholarship predating the events of 9/11 has long found that “negative images of Islam have pervaded much of the popular and political discourse, monolithically depicting a very diverse group of peoples with distinctive cultures, histories, and languages as violent, intolerant, barbaric, and out of touch with modern social norms” (Lajevardi and Oskooii, 2018, p. 118). Third, the coverage of Muslim Americans – the domestic group – is much more mixed prior to 9/11 and then after 9/11.

Figure 2: Mean Sentiment of Media Coverage Over Time

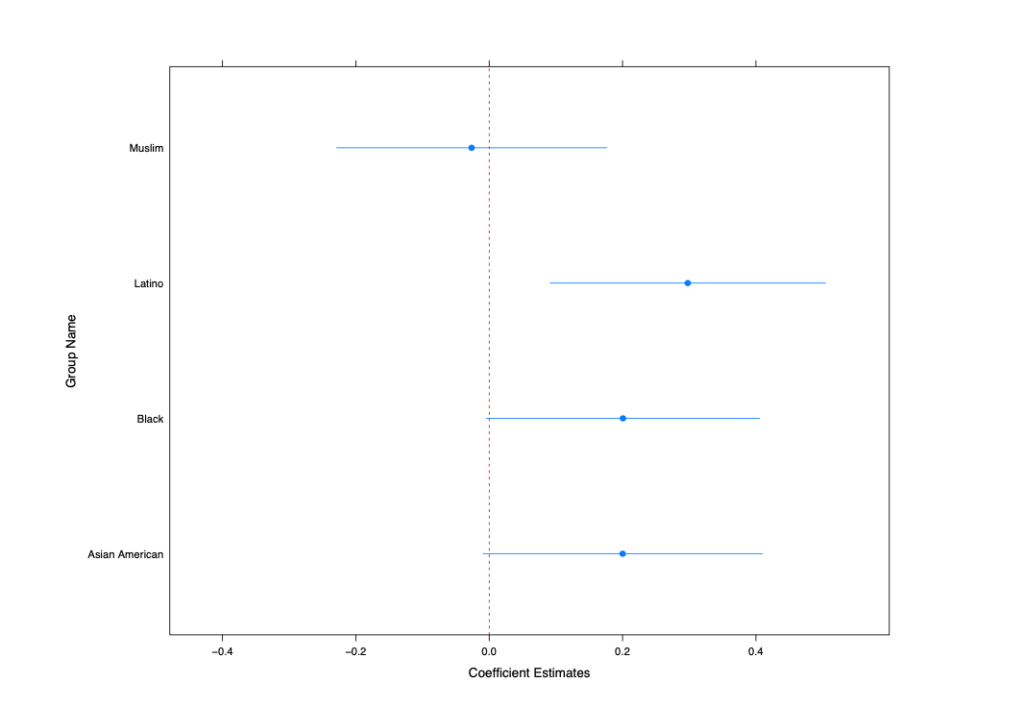

Turning to Figures 3 and 4, we see that the sentiment coverage of Muslim Americans did not significantly differ from that of Muslims, Blacks, and Asian Americans. in the pre-9/11 period. Only the sentiment coverage of Latinos was slightly and significantly more positive than that of Muslim Americans, but not by much (Figure 3).

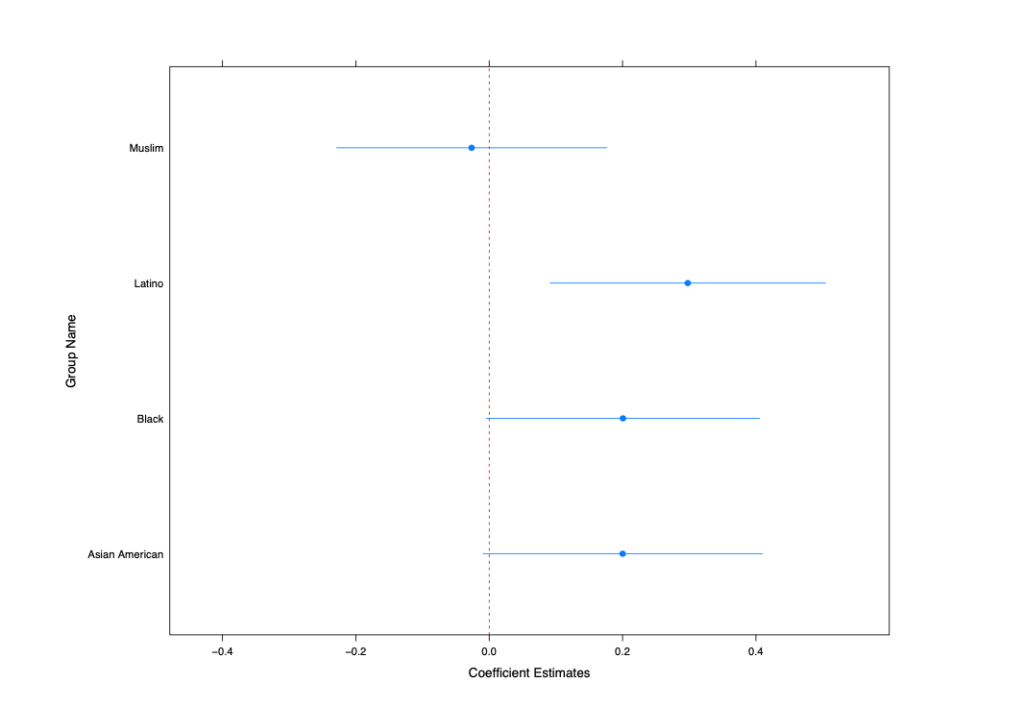

After 9/11, however, the sentiment coverage of Muslim Americans differed significantly from and fell below all other examined marginalized groups in America (Figure 4). Only the coverage of Muslims – the foreign group – did not statistically differ from that of Muslim Americans.

Figure 3: Differences from Muslim Americans in Standardized Sentiment by Group (Pre- 911)

Figure 4: Differences from Muslim Americans in Standardized Sentiment by Group (Post- 9/11)

Together, these findings are particularly noteworthy. Muslims – the foreign group – are mentioned more than some of the most marginalized groups in the American sociopolitical context. Moreover, the tone of their news coverage is decidedly negative. If the ordinary public is exposed to repeated and negative coverage of Muslim Americans, how detrimental is this coverage to the status of Muslim Americans, the domestic group?

“Together, these findings are particularly noteworthy. Muslims – the foreign group – are mentioned more than some of the most marginalized groups in the American sociopolitical context.”

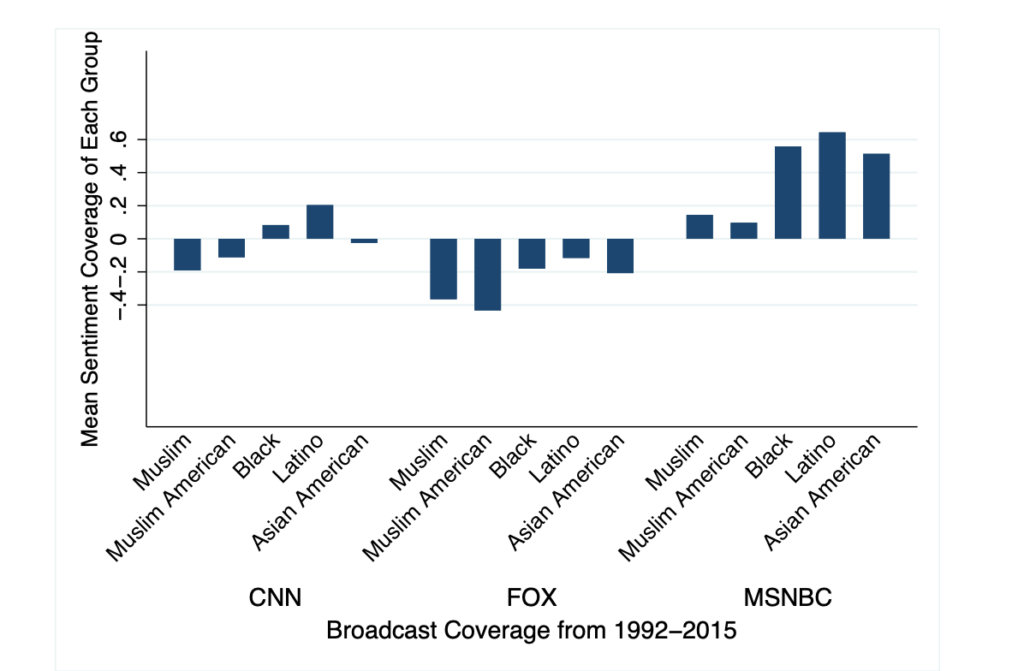

Finally, I examine whether differences in these patterns exist by network. CNN, FOX, and MSNBC are frequent targets of media bias allegations (Martin and Yurukoglu, 2017). And, there is considerable evidence that the slant of broadcast news can affect vote choice (DellaVigna and Kaplan, 2007; Martin and Yurukoglu, 2017), group attitudes (Abrajano and Singh, 2009; Gil de Zu ́n ̃iga, Correa and Valenzuela, 2012), and policy support (Feldman, Huddy and Perkins,2009; Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes, 2013; Nyhan and Reifler, 2010).

Prior work thus suggests that networks are likely portraying groups differently based on their ideological tilt. For example, Martin and Yurukoglu (2017) find that FOX grew increasingly conservative from 2000-2008, and that the consumption of its coverage slanted viewers’ political attitudes. CNN is frequently perceived to be more middle of the road. MSNBC, on the other hand, is commonly deemed to be a liberal network sympathetic to racial and ethnic minorities and the policies they espouse. “

…Over this aggregate period of time, FOX, CNN, and MSNBC consistently attribute more negative words to the coverage of Muslims and Muslim Americans than to Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans.”

Figure 5 displays the mean standardized sentiment coverage of each of the examined marginalized groups by publication medium from 1992-2015. Several important trends are worthy of note. Over this aggregate period of time, FOX, CNN, and MSNBC consistently attribute more negative words to the coverage of Muslims and Muslim Americans than to Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans. The networks, moreover, functioned as we would have expected in terms of their ideology, with MSNBC reporting on all of the examined groups more positively than FOX and CNN. After MSNBC, CNN attributed more positive words to their reporting of each of these groups. FOX used the least positive language when communicating about each of the groups, though it used slightly less negative language about Latinos. Across the board, each network communicated Muslims and Muslim Americans more negatively than the other evaluated groups.

Figure 5: Discussion of Muslims and Muslim Americans is not driven by network

Next, because Muslim American coverage did not increase in volume until after 9/11 and because Muslim American coverage appears to not significantly differ from that of other marginalized groups in the pre-9/11 period, I evaluate whether the networks discussed Muslim Americans (and other groups) differently in the pre- and post-9/11 periods. The plot on the left-hand side of Figure 6 displays the standardized mean sentiment scores of groups by network from 1992-9/11. The figure illustrates that Muslims and Muslim Americans are discussed more negatively than the other three groups across each publication platform. Moreover, MSNBC generally discussed each of these groups more positively, followed by CNN, and then FOX, indicating that the ideology of the outlet mattered for the coverage of each of the examined group.

“The figure illustrates that Muslims and Muslim Americans are discussed more negatively than the other three groups across each publication platform. Moreover, MSNBC generally discussed each of these groups more positively, followed by CNN, and then FOX, indicating that the ideology of the outlet mattered for the coverage of each of the examined group.”

The plot on the righthand side of Figure 6 displays the standardized mean sentiment score of each of these groups by publication platform from 9/11-2015. As is evident, the coverage of each of the racialized groups is more negative in the post-9/11 period than it was in the pre-9/11 period. CNN and FOX become more similar in their coverage of racialized groups in the post-9/11 period, with CNN appearing to become increasingly more negative about these groups. Finally, Muslim Americans in both the pre- and post- 9/11 periods received relatively more negative coverage than that of the other examined groups, but this coverage was more positive than the coverage they received in the post 9/11 period.

Figure 6: Sentiment of Coverage of Groups by News Source from 1992-9/11 and 9/11-2015

The results from this analysis suggest three important takeaways. First, the news media communicated Muslim Americans more negatively than other racialized American groups across all news broadcast platforms, in both the pre- and post-9/11 periods. Second, the ideology of the publication platform matters for how negatively a given network discusses marginalized groups. While FOX consistently discussed all groups negatively, MSNBC appears to have discussed Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans more positively in the pre-and post-9/11 periods. Finally, no network treated Muslim Americans similarly to other racialized groups. Rather, each network in each time period (pre- and post-9/11) discussed Muslim Americans more negatively than the other examined groups. As a result, Muslim Americans appear to not be able to reach American viewers in a positive light, even when compared to other racialized groups, who we know through prior scholarship are communicated negatively to begin with.

5-Takeaways and Conclusions

Arguably, the news media can illustrate how groups are being communicated to the public. In the case of Muslim Americans, much – if not all – of the information the public receives about the group is disseminated by the news media. The findings highlighted above provide evidence that the public has been exposed to increasing news coverage of Muslims (the foreign group), in the decade and a half after 9/11 and that much of the coverage is negative. These portrayals, moreover, are sustained by each of the major news media platforms examined. Moving forward, scholarship would be well served to address whether the tone and frequency of media coverage of the foreign group has consequences for the sociopolitical experiences of the domestic one.

*Nazita Lajevardi is a lawyer and an Assistant Professor at Michigan State University. Her research lies at the intersection of religion, race and ethnic politics, representation, and discrimination. Broadly, she examines one overarching question: How do marginalized groups fare under western democracies? Her scholarship has been published in venues, such as The Journal of Politics, American Political Science Review, and Political Behavior among others. It has also been featured in the popular media, including The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vox Magazine, and The Huffington Post.

References

Abrajano, Marisa and Simran Singh. 2009. “Examining the link between issue attitudes and news source: The case of Latinos and immigration reform.” Political Behavior 31(1):1–30.

Alsultany, Evelyn. 2012. Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation after 9/11. NYU Press.

Bhonde, Reshma, Binita Bhagwat, Sayali Ingulkar and Apeksha Pande. 2015. “Sentiment Analysis Based on Dictionary Approach.” International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology 3(1).

Brummett, Barry. 2014. Rhetoric in Popular Culture. Sage Publications.

CAIR. 2018. “Targeted: 2018 Civil Rights Report.”

Chomsky, Noam. 1997. “What makes mainstream media mainstream.” Z magazine 10(10):17–23.

Collingwood, Loren, Nazita Lajevardi and Kassra AR Oskooii. 2018. “A Change of Heart? Why Individual-Level Public Opinion Shifted Against Trump’s Muslim Ban.” Political Behavior, pp. 1–38.

DellaVigna, Stefano and Ethan Kaplan. 2007. “The Fox News effect: Media bias and voting.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3):1187–1234.

Entman, Robert M and Andrew Rojecki. 2001. The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America. Wiley Online Library.

Feldman, Stanley, Leonie Huddy and David Perkins. 2009. Explicit racism and white opposition to residential integration. In Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Association, Chicago, IL: April. Vol. 25.

Gil de Zu ́n ̃iga, Homero, Teresa Correa and Sebastian Valenzuela. 2012. “Selective exposure to cable news and immigration in the US: The relationship between FOX News, CNN, and attitudes toward Mexican immigrants.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56(4):597–615.

Gilens, Martin. 1999. “Why American Hate Welfare.” Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy, Chicago, Presses Universitaires de Chicago .

Harwood, Jake, Miles Hewstone, Yair Amichai-Hamburger and Nicole Tausch. 2012. “The idea that communication between groups results in increased inter.” Communication Yearbook 36 36:55.

Haynes, Chris, Jennifer Merolla and S Karthick Ramakrishnan. 2016. Framing Immigrants: News Coverage, Public Opinion, and Policy. Russell Sage Foundation.

Kalkan, Kerem Ozan, Geoffrey C Layman and Eric M Uslaner. 2009. “Bands of others? Attitudes toward Muslims in contemporary American Society.” The Journal of Politics 71(3):847–862.

Kellstedt, Paul M. 2000. “Media framing and the dynamics of racial policy preferences.” American Journal of Political Science, pp. 245–260.

Lajevardi, Nazita and Kassra AR Oskooii. 2018. “Old-fashioned racism, contemporary islamophobia, and the isolation of Muslim Americans in the age of Trump.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, pp. 1–41.

Lajevardi, Nazita and Marisa A Abrajano. 2019. “How Negative Sentiment towards Muslims Predicts Support for Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election.” Journal of Politics. Forthcoming.

Markham, James W and Crispin Maslog. 1971. “Images and the mass media.” Journalism Quarterly 48(3):519–525.

Martin, Gregory J and Ali Yurukoglu. 2017. “Bias in cable news: Persuasion and polarization.” American Economic Review 107(9):2565–99.

Mastro, Dana. 2009. “Effects of racial and ethnic stereotyping.” Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research 3:325–341.

Mastro, Dana E and Maria A Kopacz. 2006. “Media representations of race, prototypicality, and policy reasoning: An application of self-categorization theory.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50(2):305–322.

Merolla, Jennifer, S Karthick Ramakrishnan and Chris Haynes. 2013. “Illegal, Undocumented, or Unauthorized: Equivalency Frames, Issue Frames, and Public Opinion on Immigration.” Perspectives on Politics 11(3):789–807.

Nacos, Brigitte. 2016. Mass-mediated Terrorism: Mainstream and Digital Media in Terrorism and Counterterrorism. Rowman & Littlefield.

Nacos, Brigitte L and Oscar Torres-Reyna. 2002. Muslim Americans in the News before and after 9-11. In Symposium Restless Searchlight: Terrorism, the Media & Public Life. Harvard University.

Nacos, Brigitte Lebens and Oscar Torres-Reyna. 2007. Fueling our fears: Stereotyping, media coverage, and public opinion of Muslim Americans. Rowman & Littlefield.

Nyhan, Brendan and Jason Reifler. 2010. “When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32(2):303–330.

Panagopoulos, Costas. 2006. “The polls-trends: Arab and Muslim Americans and Islam in the aftermath of 9/11.” International Journal of Public Opinion Quarterly 70(4):608– 624.

Ramasubramanian, Srividya. 2011. “The impact of stereotypical versus counterstereotypical media exemplars on racial attitudes, causal attributions, and support for affirmative action.” Communication Research 38(4):497–516.

Saleem, Muniba, Grace S Yang and Srividya Ramasubramanian. 2016. “Reliance on direct and mediated contact and public policies supporting outgroup harm.” Journal of Communication 66(4):604–624.

Sides, John and Kimberly Gross. 2013. “Stereotypes of Muslims and Support for the War on Terror.” The Journal of Politics 75(3):583–598.

Tan, Alexis, Yuki Fujioka and Gerdean Tan. 2000. “Television use, stereotypes of African Americans and opinions on affirmative action: An affective model of policy reasoning.” Communications Monographs 67(4):362–371.

Winter, Nicholas JG. 2006. “Beyond welfare: Framing and the racialization of white opinion on social security.” American Journal of Political Science 50(2):400–420.

Winter, Nicholas JG. 2008. Dangerous frames: How ideas about race and gender shape public opinion. University of Chicago Press.

[1]https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2018/02/05/anti-sharia-law-bills-united-states

[2]https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/anti-muslim.