When I began researching the Deoband movement as a graduate student, I knew basically three things about the Deobandis: there are hundreds of madrasas around the world modelled after the original Deobandi seminary, the Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband, founded in British India in 1866; the Deobandis have generally been vociferous critics of Sufi devotional practices, like the saint’s death anniversary (‘urs), garnering them a reputation for being “anti” Sufi, even as they identify as Sufis; and the Taliban emerged out of Deobandi seminaries in northwest Pakistan. I began the dissertation seeking to ascertain how these aspects of the movement connect. I quickly realized the third aspect – connections to the Taliban – was a matter of paramount interest to journalists, policy makers, and NGOs, but of little interest whatsoever to actual, living Deobandis. But the connection between the first two aspects perplexed me. How were they related? How did Deobandis’ critique of Sufism travel? Did it travel everywhere Deobandis went, or only selectively? To whom and in what forms did Deobandis voice that critique? To answer these questions, I followed the Deoband movement from India to South Africa, home to some of the most prominent Deobandi seminaries and scores of prominent Deobandi scholars.

By the time I finished the book, Revival from Below: The Deoband Movement and Global Islam, which will be published by the University of California Press in November 2018, the project had morphed considerably. The questions above remained central. It is, still, the first extended study of Deobandis outside of South Asia, and the first to focus on the Deobandis’ relation to Sufism. But in ways I could not have anticipated, the book became an extended reflection on how the ‘ulama, traditionally educated Muslim scholars, have attempted to adapt to that complex array of epistemic, intellectual, and social shifts we call “modernity” – and to do so on their own terms.

My book situates the origins of the Deoband movement at the nexus of two such shifts: an emergent British policy of “non-interference” in the “religious” matters of Indians after the disastrous and bloody rebellion of 1857 against British rule – which, as Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst has wonderfully shown, the British believed to have “religious” causes – and early Deobandis’ efforts to fill this newly minted “religious” space. I argue that Deobandis reimagined the madrasa as a purely “religious” institution, reimagined the ‘ulama as stewards of public morality rather than civil servants and administrators, and reframed the knowledge they purveyed as “religious” knowledge distinct from the “useful” and “secular” knowledge promoted by the British.

Normative Order and Disorder: Theorizing Shirk and Bid‘a

And yet, even as the madrasa became a sort of religious enclave, perceived (rightly or wrongly) as a shelter from currents of colonial modernity, Deobandi scholars began to turn outwards towards emergent Muslim publics, conjured through the circulation of short, Urdu-language polemics and primers on belief and practice. This is the wider context in which a number of prominent Deobandi scholars began to publish critiques of Sufi devotional practices in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As I show, these critiques centered on two perceived threats to what I call “the normative order:” shirk, ascribing divine attributes to entities other than God, and bid‘a, illicit innovation in religious matters. Deobandis identified a number of sources of potential shirk, including calling for the Sufi saints’ intercession in ways that attribute quasi-divine powers directly to them, believing in the Prophet Muhammad’s presence at certain gatherings, among others.

But, in many ways, the Deobandis saw bid‘a as far more dangerous than shirk because it corrupts even well-meaning expressions of piety. Deobandis did not define bid‘a simply as anything “new” that did not exist in the time of the Prophet; bid‘a, rather, was anything that simulated the normativity of revelation. What makes bid‘a insidious is that it includes many things that the average Muslim would take to be perfectly acceptable, even praiseworthy. Something as ostensibly commendable as honoring the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday, known as mawlud or milad (Arabic, “birth”), became a paramount source of normative disorder when lay Muslims began to practice it with the same degree of reverence or regularity with which they practiced, say, their five daily prayers or fasting during Ramadan.

The ‘Ulama in a World of Print

“The Deobandis sought to walk an interpretive tightrope between educating Muslims just enough to know the spiritual dangers of mawlud, ‘urs, and other practices, but not so much that Muslims arrogated to themselves the authority to opine on these practices without the input of the ‘ulama. ”One of the counter-critiques that lay Muslims levelled against Deobandis was that they simply got it all wrong: lay Muslims, they say, know the difference between salat (a ritual commandment) and the mawlud (an optional and entirely natural expression of love for the Prophet). I return to these lay Muslim contestations of Deobandi critiques below. For now, I want to home in on a certain hermeneutic anxiety at the core of the Deobandi reformist project – one that vexes many clerical movements (and not just in Islam) that deploy print as a medium of reform. In the short pamphlets and primers they wrote for lay Muslim audiences – Ashraf ‘Ali Thanvi (d. 1943) alone wrote scores of these, such as his Ta‘lim al-Din (Instruction in Religion) of 1897 or his Islah al-Khayal (Reformation of Thought) of 1901 – the Deobandis sought to walk an interpretive tightrope between educating Muslims just enough to know the spiritual dangers of mawlud, ‘urs, and other practices, but not so much that Muslims arrogated to themselves the authority to opine on these practices without the input of the ‘ulama. That is, there is a constant tension between harnessing the power of print to do reform and wariness about the (false) interpretive independence that print creates among readers. Borrowing language from the historian Nile Green, I describe this as a tension between the bibliocentric and the anthropocentric – that is, between knowledge mediated by print alone, and knowledge vouchsafed by the affective power and presence of those who embody that knowledge. In the book, I write, “Deobandi tradition arises out of a tension—sometimes productive, sometimes strained—between the anthropocentric and the bibliocentric, between the centrifugal force of a global movement and the centripetal force of intimate encounters, between the dispersal of books and the proximity of bodies.” I suggest we cannot understand the Deobandi movement, and perhaps global religious movements more broadly, without understanding this tension.

“Deobandi tradition arises out of a tension—sometimes productive, sometimes strained—between the anthropocentric and the bibliocentric, between the centrifugal force of a global movement and the centripetal force of intimate encounters, between the dispersal of books and the proximity of bodies.”How did Deobandis try to mitigate it? In the book, I argue that they mobilized the classical Sufi concept of companionship (suhbat) between master and disciple to reassert the importance of the person-to-person transmission of knowledge and affect, without which religious knowledge derived from books alone can be unreliable, even dangerous. For the Deobandis, the madrasa and the khanqah, the seminary and the Sufi lodge, became dual, complementary spaces of reform, where individuals learn piety from the living presence of those who are already reformed. But do most Muslims have time to devote themselves to a Sufi master and spend time in a khanqah? Certainly not. Cognizant of this, Deobandis sought to adapt Sufism itself around the busy lives of emergent “middle-class” professionals to whom they directed their reformist literature. Ashraf ‘Ali Thanvi, for instance, wanted to make Sufism more accessible, even “easier.” Part of making Sufism “easier” was making it more palatable to modern sensibilities. One of the classic Sufi techniques of disciplining the lower self (nafs) entailed depriving the body of basic desires – typically food, sleep, conversation, and social interaction. Thanvi replaced the older Sufi practice of “abandoning” (tark) these desires with a “reduction” (taqlil) in them. He regarded deliberately subjecting oneself to physical extremes to be self-indulgent. Thanvi said the “hardship and severity” to which some Sufis subject themselves was a bit like walking to the next town to draw water for ablutions when there is plenty of water nearby.

Sufism is For Everyone

Yet another way that the Deobandis tried to make Sufism more accessible was simply by asserting that Sufism is fundamentally about ethics – specifically, divesting the self of negative character traits and “adorning” the self with noble ones. Any reader with even a cursory knowledge of Sufism will immediately recognize that this is a central feature, if not a sine qua non, of Sufism from the classical period to the present. Deobandis’ appropriation of this discourse differs slightly from their predecessors in two respects. First, they asserted that Sufism is “obligatory” for all Muslims. This, too, was not wholly original with the Deobandis; earlier scholars they cite, such as Qazi Sanaullah Panipati (d. 1810), made similar claims. But what did such a claim mean in practice? To be sure, they did not intend that all Muslims had to find a Sufi master (although they strongly encouraged it); rather, they meant that Sufi ethics are obligatory. In the book, I argue that the very possibility of regarding Sufism as “obligatory” presupposes distilling Sufism down to its ethical core. It’s not that Deobandis dismissed saintly devotions, for example, as marginal; they believed that reverence for the saints was a means to achieve ethical self-formation, not an end in itself.

Second, Deobandis asserted not only that any pious Muslim could be a “saint” (wali) but, in fact, was a saint by virtue of that piety. This claim, likewise, is not completely unprecedented. As I show, the idea emerges out of Muslims’ engagement with the polyvalence of wali (ally, friend, guardian, and by extension in Sufi contexts, “saint”) in the Qur’an. As early as al-Kalabadhi (d. 990), Sufis recognized two levels of wali: that which is “common to all believers,” a walaya ‘amma, and that which is particular to God’s elect, a walaya khassa. The Deobandis, I argue, mined the semantics of walaya ‘amma to articulate, quite explicitly, the idea that any pious Muslim is a ‘saint’. Thus, as Thanvi writes in his Bihishti Zewar – a textbook of Deobandi reform if there ever was one: “When a Muslim worships faithfully, avoids sin, maintains no love for this world, and obeys the Messenger in every way, then he is a friend of God [Allah ka dost] and God’s beloved. Such a person is called a wali.” And yet, in books written for his disciples, Thanvi recognized many degrees of walayat, the highest of which was “technically speaking [istilahan] … who we call a wali.” Here we see that Thanvi implicitly recognized the ‘conventional’ meaning of wali (overlapping imperfectly, but indisputably, with the English ‘saint’), even as he sought to expand the parameters of Sufi sainthood. This is not a contradiction as much as one message calibrated for two very different audiences, nor is it a critique of Sufi sainthood as much as a logical extension of the Deobandi project.

Debating Sufism and Muslim Politics in Apartheid South Africa

What I have described thus far encompasses much of the first four chapters of my book. The final three chapters track this nexus of ideas and critiques as they move across the Indian Ocean with the migration of tens of thousands of Muslims from India to southern Africa in the period from 1860-1911. This ‘Indian’ stream of migrants intersected with an older one, that of ‘Malay’ Muslim who came from the Dutch East Indies, many as slaves, and settled in the Cape – such as the renowned Sufi Sheikh Yusuf (d. 1699), whose tomb is pictured. Importantly, the earliest “Deobandi” scholars in South Africa functioned as the vast majority of graduates from its institutions have always functioned: as (mere) ‘ulama. That is, they were specialists in Islamic belief, worship, theology and law, who served Muslims as preachers, imams, writers, and teachers. If they expressed any critical views of practices they deemed bid‘a and shirk, for instance, this was not couched in the idea of a ‘Deobandi’ identity, nor was it the focus of their work as ‘ulama. This began to change in the 1960s, with the global rise of the Tablighi Jama‘at, an offshoot of the Deoband movement. The Tablighis sought to translate the Deobandi project into a tangible program, one that, I argue, was characterized by the same ambivalences and interpretive anxieties we see in earlier Deobandi works. I track how the rise of the Tablighi Jama‘at intersected with, but was also distinct from, the rise of South African Deobandi seminaries, beginning in 1973 with the Dar al-‘Ulum Newcastle. (Before 1973, South Africans had to travel to the subcontinent to study in a Deobandi institution.)

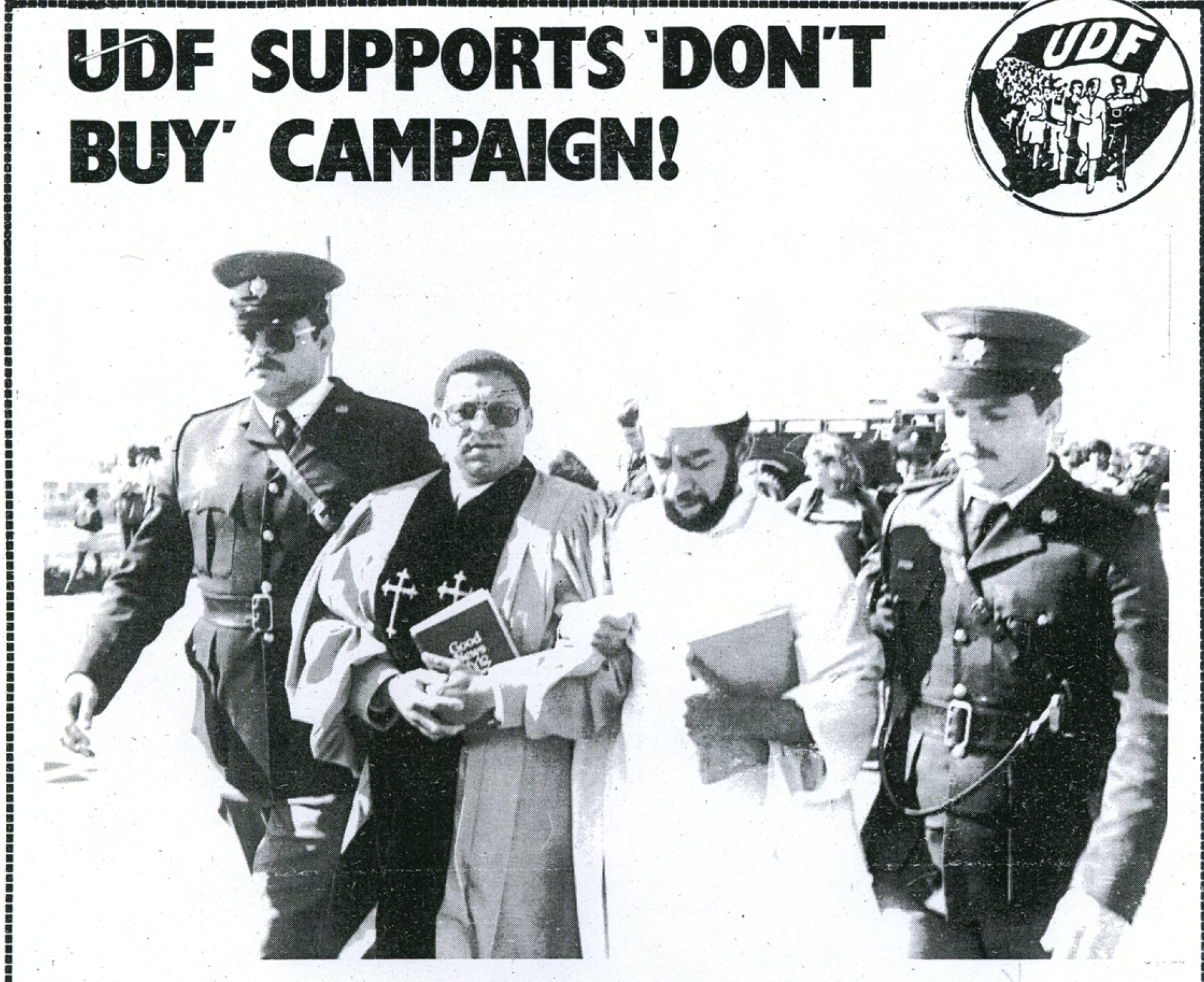

“As Deobandi scholars criticized Muslim activists for mobilizing against apartheid alongside activists of other faiths, and justified that position through Sufi vocabularies, a growing number of Muslims lambasted Deobandis for their alleged collaborationist stance toward the apartheid regime, and articulated their politics through devotional practices like the mawlud.”The Tablighis were the engine of Deobandis’ public ‘brand,’ in South Africa and elsewhere. Beginning in the 1970s, Tablighis and other Deobandis began to engage in pamphlet wars and even physical altercations with Barelvis, their subcontinental archrivals, with whom they are virtually identical (both are Sunni, Sufi, Hanafi in law, Ash‘ari or Maturidi in theology, and rooted in global madrasa networks) except for key differences on questions of God’s sovereignty and the Prophet Muhammad’s metaphysical status. Nonetheless, these differences formed the basis for the intense polarization of the Deobandi-Barelvi rivalry, a rivalry that traveled wherever Deobandis and Barelvis traveled. In the final chapter of the book, I show how the Deobandi brand, and Deobandis’ local critiques of South African Sufi practices became the object of intense public debate in South Africa, especially from the 1970s onward, and I detail how this debate intersected with a markedly different one: whether, to what extent, and in what ways Muslims should mobilize against the apartheid regime. Non-Deobandi Muslims, especially Muslims of non-Indian background, lambasted South African Deobandi ‘ulama for their perceived apathy towards challenging the government or supporting Muslims who did. In this context, Tablighis’ assaults on a mawlud outside of Johannesburg, to take one example from the book, struck other Muslims as myopic at best. As I explored these archives, what I found especially fascinating was how contestations over Sufism – defining it, critiquing it, defending it – became a fundamental part of these public debates over activism and Muslim politics. As Deobandi scholars criticized Muslim activists for mobilizing against apartheid alongside activists of other faiths, and justified that position through Sufi vocabularies, a growing number of Muslims lambasted Deobandis for their alleged collaborationist stance toward the apartheid regime, and articulated their politics through devotional practices like the mawlud. The public face of Deobandi opposition to the Muslim anti-apartheid movement was Ahmed Sadiq Desai, whose main publication, The Majlis, re-presented Deobandi critiques in a vituperative and highly-condensed form, largely shorn of its hermeneutic nuance. Desai criticized, among other things, the inter-religious solidarity against apartheid that formed between figures such as imam Hassan Solomon and the reverend Allan Boesak, pictured here after being arrested during a United Democratic Front protest. In Desai’s view, Sufism called for Muslims to remain above the fray of politics, especially the politics of the street, and especially in a country where Muslims were a minority and Shari‘a had little, if any, sway in public discourse.

The Deoband Movement and Global Islam

What does all this tell us about the Deoband movement, and of global Islam? I want to conclude with two ways of answering that question – one fairly obvious, one not so obvious. First, we take it for granted that ‘global Islam’ is not monolithic. Nevertheless, it bears repeating that individual Islamic movements are similarly fraught with tensions, ambivalences, and outright contradiction. The tensions that define the global Deoband movement play out locally in interesting and sometimes surprising ways. In the book, I explore occasions when South African Deobandis broke with Deobandis back ‘home’. To take one example, in 1963, the chancellor of Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband, Qari Muhammad Tayyib, toured South Africa, where he was asked by a Durban businessman whether Muslims there could participate in interest-bearing business transactions, known as riba, which Islamic law customarily forbids. Responding to the businessman’s inquiry, the Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband issued a fatwa declaring South Africa a dar al-harb (‘abode of war’), where the standard rules forbidding riba do not apply. The reaction from South African Muslims was so severe in its condemnation – especially the suggestion that South Africa was an ‘abode’ of perennial conflict between Muslims and non-Muslims – that a Deobandi ‘ulama council in Johannesburg publicly rejected the fatwa and the Hanafi precedent on which it was based, arguing that the Qur’anic ban on riba is unequivocal and applies in any context.

Second, the not-so-obvious conclusion: the polemics surrounding the Deoband movement in South Africa were, I suggest, the outcome of the bibliocentric ‘winning out’ over the anthropocentric. In the book, I call this a “loss of a certain sensibility at the heart of Deoband, one in which the core aspirations that Deobandis articulated in the first half of the twentieth century – a tradition handed down through the carefully cultivated dynamic between books and bodies, grounded in the intricately theorized interplay between madrasa and khanqah, hopeful about the power of print to implement reform but wary of its implications – gave way to a text-driven, superficial, ossified tradition,” represented by Desai in South Africa.

In the conclusion, I reflect on what this might, in turn, tell us about the rise of the Taliban. I will not delve into that argument here. But I will say, in brief, that the Deoband movement, like any global Islamic phenomenon, must be studied locally, in context, with close attention to the mutually constitutive ways ‘religion’ and ‘politics’ inform how we understand acts of violence, especially when critics blame the Deoband movement wholesale for attacks on Sufis in Pakistan and elsewhere. At the very least, I hope my book can acquaint readers with a movement that has fundamentally shaped modern debates about Sufism, Islamic law, Muslim politics, and the roles the ‘ulama should play in the daily lives of lay Muslims.