Masooda Bano, Female Islamic Education Movements: The Re-Democratisation of Islamic Knowledge (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017) 262 pages. $99.99 hardback.

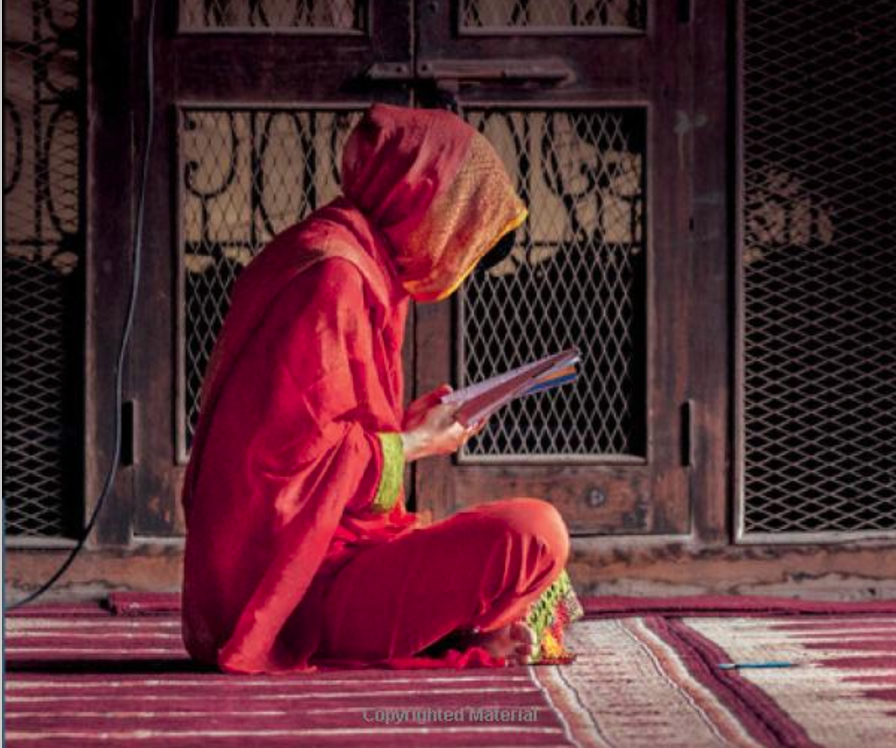

“The women’s turnout at Tahajjud prayer during the last ten days of Ramadan was in particular overwhelming … especially the 27th night, some women had to pray on the road outside the mosque, despite the fact that the three-storey women’s section had space to accommodate almost 1,000 worshippers.” (156) This quote describes the unexpected scene Masooda Bano faced in Damascus, Syria in 2010. For the pre-dawn volunteer tahajjud prayers, when one would otherwise assume that women were at home, young and old women came in masses to the Lala Basha Mosque during Ramadan. This phenomenon, observed by Bano, is a new one that reflects the revival of Islamic education movements across the Muslim world. Although the situation she witnessed in Damascus during Ramadan in 2010 might have been unique, Bano observed similar revivals of female Islamic education movements and public female religious participation in three otherwise very different parts of the Muslim world: Pakistan, Syria, and Nigeria. Thus, this book is a comparative study that discusses the histories of these movements, their similarities and differences, and the contexts they are (or were in the case of Syria) developing in.

“Although Bano demonstrates that a rise in female Islamic education has been taking place in these otherwise unrelated areas since the 1970s, her central argument goes beyond this observation. She argues that the socio-economic levels of the women that are included in Islamic education movements is crucial, and that the backgrounds of these women are essential in understanding how Islamic knowledge is taught and defended by both male and female teachers.”

Although Bano demonstrates that a rise in female Islamic education has been taking place in these otherwise unrelated areas since the 1970s, her central argument goes beyond this observation. She argues that the socio-economic levels of the women that are included in Islamic education movements is crucial, and that the backgrounds of these women are essential in understanding how Islamic knowledge is taught and defended by both male and female teachers. Thus, she shows that the highly educated women that are increasingly a part of Islamic education movements are demanding proper explanations for the teachings they are following, they are no longer content to simply follow instructions. She does not argue that this leads the women to leave orthodoxy, nor accept modernist arguments without question, but rather, that the women demand to learn and know the sources and methodologies that lead to the answers they are given by their teachers.

In the formal schools in Pakistan, Nigeria, and Syria the main topics taught are Qur’ān, hadith, sīra, tafsīr, and Islamic History (97). In the informal study circles women in all three countries from “modern-educated and liberal backgrounds” requested to study philosophical and mystical works such as those by al-Ghazali, Rumi, and Ibn al-Arabi (98). However, in both settings Bano argues that well-educated women find ways to balance their modern lives with what they are learning and question the relevance of some Islamic teachings, thus impacting what and how knowledge is taught (85). This leads to a process Bano named a “re-democratisation” of knowledge, where women are having a greater say in the way knowledge is taught and the topics that are covered by Islamic scholars (the ‘ulama), by demanding that they cover issues relevant to the women. Thus, women do not just attend classes and study circles to maintain tradition, but rather, partake in them because they are relevant to their lives (167).

Unfortunately, Bano does not clearly lay out the issues that the “modern” women are drawn towards and the teachings they are critical of. I suspect that this is because this differs a lot from one context to another – however, more examples would have strengthened her argument.

Although the focus of the book is on women as consumers of education, reading between the lines one realizes that women also serve as a large proportion of the teachers. Unfortunately, it is not always clear whether or not this is the case. There is also no discussion of the experiences of women who study with a male teacher versus those who study with a female teacher. Including clear information about who the women were studying with as well as a comparison of male and female teachers would have benefitted the study.

“The study is based on fieldwork Bano conducted in Pakistan from 2006, Northern Nigeria in 2008, and Syria in 2010 where she interviewed female preachers and scholars, female students, and participated in the learning circles herself… The thee geographical areas were chosen as they represent three important areas of the Muslim world (South Asia, the Arab Middle East, and West Africa), however, the author admits that she also chose these localities as they were accessible to her”

The study is based on fieldwork Bano conducted in Pakistan from 2006, Northern Nigeria in 2008, and Syria in 2010 where she interviewed female preachers and scholars, female students, and participated in the learning circles herself. She also conducted interviews with important members of the ‘ulama, government officials, and NGO workers (44). The thee geographical areas were chosen as they represent three important areas of the Muslim world (South Asia, the Arab Middle East, and West Africa), however, the author admits that she also chose these localities as they were accessible to her (41). The development of the movements in these three geographical areas developed independently of one another and are manifested in quite different ways. For example, in Pakistan a network of female only madrasas that issue formal four-year degrees developed, whereas in Syria the women mostly got their education through halaqas (study circles) in mosques or homes (3). Yet, all three areas have both formal and informal avenues for women to receive Islamic education, and in all three contexts the informal groups mostly consisted of women from elite groups of the society (97-98).

Although the three geographies are very different from one another, Bano highlights a common denominator that have impacted the developments of Islamic knowledge in the three countries, namely that they are all post-colonial localities (133) According to Bano, it is only in this context that the decision to include women even in “ultra-conservative” settings can properly be understood (212), as the ‘ulama saw the education of women as the best defense against the adoption of Western cultural norms and the protection of Islamic family values (148).

The situation in Syria has of course changed a lot since Bano conducted her field work in 2010. Although that means that the landscape she describes in Aleppo and Damascus is no longer the same, her study is still very important. As Bano points out, scholarship such as hers on life in Syria just before the outbreak of the Arab Spring and subsequent war will be important in a post-conflict setting both as it serves as a model for how things used to be, and because it will help scholars understand changes in religious, social, and political movements in Syria (43-44).

Because of its transregional focus, Female Islamic Education Movements should appeal to scholars of South Asia, the Levant, and West Africa alike. The study is placed within Religious Studies and Anthropology, but a wider audience from Women’s studies and Education may also be interested in the book given its content. Finally, the book is approachable – this makes it also of interest to the general reader who wants to know more about women’s religious lives in these three parts of the world.