Malaysia has held regular elections since its independence in 1957 and it has been ruled by the same political coalition ever since – until this month’s 14th General Elections, where the opposition dramatically and unexpectedly defeated the Barisan Nasional coalition. The new ruling coalition, Pakatan Harapan, won 122 out of 222 seats in the Parliament. Dr. Mahathir Mohamad’s coming back out of retirement and becoming the world’s oldest prime minister at the age of 92 is truly a story for the ages.

The elections make case for turning our gaze to the Southeast Asian region, where democracy has been in the retreat for at least a decade. Good news for democracy lovers has been in short supply in 2017, the year in which democracy faced some of the most serious challenges in decades, according to Freedom House.

The Malaysian elections give us five important lessons in democratization and democracy promotion.

Democracy takes time

Political scientists have long maintained that democratization is a long and messy process, coming in waves, and sometimes resulting in reversals and democratic breakdowns. Waves are facilitated by many factors, including legitimacy deficit by authoritarian regimes, global economic policies, shifts in social climate, and neighborhood effect. Breakdowns happen due to elite contestations where some of the elites do not buy into democratic rules of the game.

The year 1998 was crucial to democratization in Indonesia and Malaysia. Due to the global financial crisis and its devastating effects on the region’s economies, protests broke out in several countries including Indonesia and Malaysia. The Indonesian people were successful in overthrowing Suharto’s authoritarian regime under the Reformasi movement.

“The year 1998 was crucial to democratization in Indonesia and Malaysia. Due to the global financial crisis and its devastating effects on the region’s economies, protests broke out in several countries including Indonesia and Malaysia…”

In Malaysia, the then-Prime Minister, Dr. Mahathir Mohammad, sacked his Deputy, Anwar Ibrahim. The latter led the first mass protest movement in modern Malaysian history. He was eventually jailed on trumped up charges, but continued mobilizing the opposition. Twenty years later, Mahathir and Anwar joined forces once again to oust Najib Abdul Razak who was widely considered to be corrupt. They succeeded by mobilizing a broad coalition of social and political actors: ethnic nationalists of different stripes, as well as moderate Islamists and socialists. It took twenty years of experimentation to produce this coalition.

Authoritarianism has been on the rise in the region during the last decade – until now. Democracy may sometimes pop up unexpectedly but rarely without hard and long work.

Islam and democracy can coexist

Two majority-Muslim nations in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Malaysia, are democracies. Combined, they have almost as many Muslims as all of the countries in the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region. Indonesia led the democratization efforts in the region some twenty years ago, after more than four decades of authoritarian rule. There has been a slight democratic decline in Indonesia during the last decade. With the coming presidential elections in 2019, it is hoped that the neighborhood effect will now spill over from Malaysia – reinforcing democratic institutions and structures in Indonesia once again. Other countries in the region are already feeling the buzz of the Malaysian elections, but the road to democracy remains thorny. With the Philippines slipping into authoritarianism under President Duterte, the two Muslim nations of Southeast Asia may be the only two remaining democracies in the region. These two countries provide a solid counter-narrative to claims that Muslims and democracy cannot co-exist.

“With the Philippines slipping into authoritarianism under President Duterte, the two Muslim nations of Southeast Asia may be the only two remaining democracies in the region. These two countries provide a solid counter-narrative to claims that Muslims and democracy cannot co-exist.”

Leadership matters

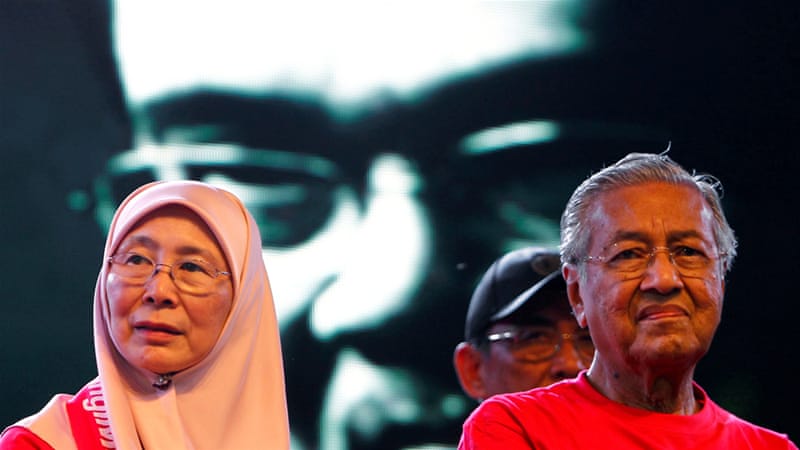

Who leads matters, but how they lead may matter even more. Mahathir has already exhibited more inclusive and conciliatory postures since assuming the office.

But the elections weren’t just about Mahathir. His relationship with Anwar Ibrahim was crucial and the two men decided to put the past behind them. Anwar’s public forgiveness of Mahathir’s sending him to jail is of Mandela-like proportions. Having spent eight of the past twenty years in jail, all the while organizing the opposition and staying true to principles of democracy, inclusion, inter-ethnic and inter-religious cooperation, Anwar Ibrahim offers a case study in political leadership.

His wife, Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, is the unsung hero, who carried the opposition through this period and found ways to reconcile among men of different ethnic backgrounds and political orientations. She is the new Deputy Prime Minister and has truly emerged as an example for young women in her country – and the world.

Social media provide an outlet for social protest

“But the elections weren’t just about Mahathir. His relationship with Anwar Ibrahim was crucial and the two men decided to put the past behind them.”When Anwar Ibrahim mobilized the opposition to Mahathir in 1998, his movement led to the emergence of cyber-activism in Malaysia, creating a large number of websites dedicated to his cause. In the pre-Facebook, pre-Twitter era, and with strong government controls over the traditional media, cyber-activism led to popular mobilization and allowed the opposition to create its own narrative without the government’s interference. They were also helped by unintended consequences of the Malaysian government’s MSC Bill of Guarantees – aimed at promoting web-based entrepreneurship for Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) – with one of these guarantees being no censorship of the Internet.

In 2018, very few believed the government campaign propaganda consisting of state-owned TV and satellite channels, and the printed media. Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp were the main platforms for political messaging and exchange. They allowed the opposition politicians to reach the grassroots without the government’s interference. Social protest via cyber-activism is a powerful tool for political awareness and mobilization. No wonder many authoritarian governments are putting restrictions on web-based social media.

Institutions matter

The 2018 Malaysian elections are a powerful example of the importance of political institutions. Prior to independence, the British negotiated a Westminster-style parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy with the Malayan leadership. Most early Malaysian leaders were British-trained lawyers who upheld the rule of law and constitutionality. This created a political culture with the strongly embedded beliefs in democratic procedures and institutions.

“In the end, Malaysia is still in uncharted territory. It remains to be seen if the new government will honor its campaign promises of creating a more democratic, more transparent form of governance.”At the same time, prior to the current election, Malaysia had no experience with transitions of power from one party or coalition to another, the mark of a consolidated democracy. Even though the Election Commission of Malaysia did not announce official results until the next morning – contrary to previous practices – it had no choice but to do so. The Constitution prevailed and everyone followed the rule of law. Institutions matter, but building their legitimacy is a lengthy process.

In the end, Malaysia is still in uncharted territory. It remains to be seen if the new government will honor its campaign promises of creating a more democratic, more transparent form of governance. A good start would be: eliminating the laws that limit freedom of expression and provide for government ownership of the media; instituting greater transparency, checks and balances; securing independent judiciary; de-politicizing civil service; and removing controls over university campuses – among other things. These are the expectations of the majority in Malaysia, and the promises given by the now ruling coalition during the campaign.