Hale Inanoglu presented an earlier version of this review essay at the 2017 Book Review Colloquium on Islamic and Middle East Studies organized by Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at George Mason University.

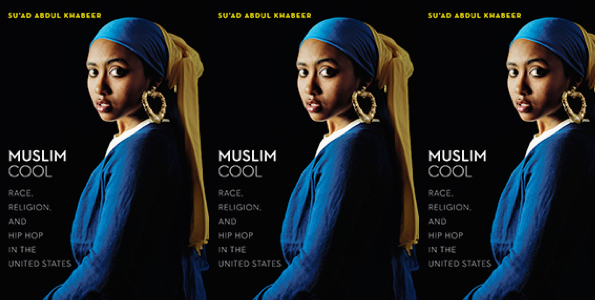

Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States by Su’ad Abdul Khabeer. NYU Press, 2016. 288 pages. $30. Reviewed by Hale Inanoglu

In her performance ethnography Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States , based on more than ten years of field work, Su’ad Abdul Khabeer studies the relationship between race, religion, and culture in the contemporary United States. In line with new research focusing on where Muslims fit within the U.S. sociopolitical landscape, her work broadly addresses the need for a “moderate,”“good” and “cool” Muslim in this context. Her research unsettles the racialization of Muslims as foreign and as constant threats to the United States.

“In line with new research focusing on where Muslims fit within the U.S. sociopolitical landscape, her work broadly addresses the need for a ‘moderate,’ ‘good’ and ‘cool’ Muslim in this context.”

The central argument of her book is that Muslim Americans cannot escape Black Islam and the interaction between Muslimness and Blackness challenges and reconfigures U.S. racial hierarchies. Her interlocutors, who she refers to as “my teachers,” navigate through and reconstitute their racialized identities with reference to hip hop. Abdul Khabeer’s research is the outcome of her engagements with two cohorts of Muslim Americans in the Chicagoland Muslim community. The first group comprises 18- to 22-year old youth leaders in arts-based social activism, primarily at IMAN—Inner-City Muslim Action Network. The second group is a slightly older cohort of young adults in their late twenties and early thirties.

Paradox and Loop of Muslim Cool

Abdul Khabeer coins some seemingly paradoxical terms. One such term is “hip hop as epistemology” (2). Being “Muslim” and being “cool” are terms that are not often associated with each other. ”. It is how you come to know yourself and how the world works. However, “hip hop as epistemology” is also a force that changes who you are in the world. It shifts your being in the world. In this respect, the author is making a metaphysical claim. “Muslim cool” is what Abdul Khabeer uses to describe a way of being and thinking about what it means to be Muslim in the United States. Coolness is attributed to being Muslim because it engages blackness to counter anti-blackness, and Muslimness to counter anti-Muslimness through hip hop culture. Hip hop is simultaneously cool and Islamic for her teachers. “Muslim Cool” also highlights how Islam is indigenous to America and can neither be extracted nor ignored.

“Hip hop is simultaneously cool and Islamic for her teachers.”

Chapter 1, “The Loop of Muslim Cool: Black Islam, Hip Hop, and Knowledge of Self,” begins by tracing the loop of Muslim Cool. Throughout her book, Abdul Khabeer asserts that Black Islam is both American and Muslim. Islam, as practiced in U.S. Black American communities, is shaped by hip hop, which in turn shapes young twenty-first-century U.S. Muslims who resort to Blackness and Islam as a way of thinking and being Muslim. Abdul Khabeer shows the ways in which hip hop, Black Islam, and the history of Black subjection in the United States serve to locate themselves in the American Muslim landscape. Chapter 2, “Policing Music and the Facts of Blackness,” examines the meanings of race and Blackness within U.S. Muslim communities by exploring the contested musical context of U.S. American Islam. In this chapter, she argues that Black music is targeted for two parallel tracks of regulation: disavowal and instrumentalization. Abdul Khabeer engages U.S. American Muslim debates around music to show “both the complexities of inter-ethnic, intra-Muslim relations and the ways in which these internal Muslim debates reflect primary engagements with Blackness in the United States today” (23).

“Abdul Khabeer engages U.S. American Muslim debates around music to show ‘both the complexities of inter-ethnic, intra-Muslim relations and the ways in which these internal Muslim debates reflect primary engagements with Blackness in the United States today’ (23).”

Intersections of Muslim Cool

In Chapters 3 and 4, Abdul Khabeer explores Muslim Cool as racial-religious self-making that happens at the complex intersections of race, class, gender, and style. Chapter 3, “Blackness as a Blueprint for the Muslim Self,” begins by investigating a specific headscarf style, the “hoodjab,” to unearth how Blackness, interpolated through the hoodjab, gives meaning that is not uncontested, to how females practice Muslim Cool. Chapter 4, “Cool Muslim Dandies: Signifyin’ Race, Religion Masculinity, and Nation,” explores the fashion interventions of men Abdul Khabeer calls Muslim dandies. She asks: “how do Muslim men use dress to claim a U.S. American identity that directly confronts white supremacist ideas of Black pathology and likewise, hegemonic ethno-religious aesthetics that render U.S. Black American Muslim men marginal in many U.S. American Muslim contexts?” (23).

“Chapter 3, ‘Blackness as a Blueprint for the Muslim Self,’ begins by investigating a specific headscarf style, the ‘hoodjab,’…”

Chapter 5, “The Limits of Muslim Cool,” shifts the discussion from interracial and gender dynamics to the dynamics of Muslim Cool’s relationship to and entanglement with the state. It explores the ways Muslim Cool cannot escape neoliberal regimes of knowledge and power, as well as U.S. imperialism. Abdul Khabeer traces the constraints this entanglement places on her Muslim teachers’ aspirations to reproduce a Black radical alterity to reveal the limits of Muslim Cool’s resistance to hegemony. Muslim Cool concludes by reflecting on the relevance of the concept to contemporary struggles against anti-Blackness and anti-Muslimness: “Blackness at the intersection of power and inequality is the contextual backdrop from which Muslim Cool emerges. Muslim Cool is an articulation of Islam, as religious belief and practice, through social justice” (221).

Methodology and Context

This timely book is notable for its intersectionality, methodology and global/local focus. Muslim Cool is a discourse, an epistemology, an aesthetic and an embodiment (2) that is forged at the intersection of Islam and hip hop and draws on being Muslim and Blackness. Muslim Cool contests two overlapping systems of racial norms: White American normativity on the one hand and the dominant ethno-religious norms of Arab and South Asian US American Muslim communities on the other.

“Muslim Cool contests two overlapping systems of racial norms: White American normativity on the one hand and the dominant ethno-religious norms of Arab and South Asian US American Muslim communities on the other.”At IMAN, one of Abdul Khabeer’s field sites, intersecting identities that are often made invisible by these hegemonic racial and religious norms were both visible and valid. Similarly, at Progress Theater, an ensemble founded by two Muslim Black women, women are allowed to perform through theater, poetry and song, all instances that would not be prescribed by the hegemonic Arab and South Asian Muslim communities in the U.S.

Although Abdul Khabeer’s performance ethnography is an innovative methodology, it is an approach that has an embedded politics. As such it has the limitations of employing a politics of aesthetics that Abdul Khabeer does not directly acknowledge until the last chapter. This method consists of staged cultural performances based on ethnographic data from specific spheres of (a) subjects whose lives are being performed, (b) the audience and (c)the performers. Using this methodology enables the researcher to communicate a sense of “immediacy, breadth and complexity of issues” (18). Abdul Khabeer enters this field through her piece Sampled: Beats of Muslim Life, thus ensuring that “she is there.” Using this methodol

ogy, she documents, explores and interrogates the key themes of Muslim Cool without explicitly connecting institutional political activism with history.

Muslim Cool primarily focuses on Islam in North America. However, I would argue that the local cannot escape the global. Black Islam, an amalgamation of local and transportable practices, developed by interacting with not just different forms of Islam, but also with indigenous and non-Muslim cultures. Through her work Abdul Khabeer shows how her teachers are coping with the hegemony of white supremacy as well as Arab and South Asian Islam. Effectively, the local is entangled with the global whether in the form of neoliberal policies or the Muslim umma.

“Through her work Abdul Khabeer shows how her teachers are coping with the hegemony of white supremacy as well as Arab and South Asian Islam.”

Embodied Politics

Although this is an excellent monograph tracing the lived experiences of American Muslims, there are two critiques that I would like to pose. My first critique targets Abdul Khabeer’s proposal to use hip hop and, by extension, Black Islam to resist and challenge white supremacy. Both hip hop and Islam would be considered fringe cultures in relationship to white hegemony. I would argue that coupling one underprivileged culture with another would ease the hegemony of white supremacy. My second critique relates to how Abdul Khabeer readily accepts her teachers as Muslims. There is a lack of clarity on the unifying characteristic of her teachers. Proposed faith and hip hop seems to be the unifying elements. However, as many orthodox Muslims would not consider hip hop Islamic, Abdul Khabeer’s goal of redefining inter- and intra-Muslim relationships falls short of engaging deeply divided communities.

In terms of her methodology, although she portrays her teachers as capable subjects who are transforming themselves and communities through hip hop, her findings cannot be decontextualized. Abdul Khabeer’s subjects are the products of their “unique” contexts and might be difficult to relate to within the broader Muslim and American communities. Moreover, Muslim Cool’s loop of hip hop does not form a loop with others whether American or Muslim. Her study would greatly benefit from incorporating how her teachers are perceived within the broader U.S. context. These

“Muslim Cool’s loop of hip hop does not form a loop with others whether American or Muslim. Her study would greatly benefit from incorporating how her teachers are perceived within the broader U.S. context.”connections can be highlighted through conversing with prior literature on this topic. Hisham Aidi’s Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture (2014) is a great example. Even though Abdul Khabeer briefly mentions Aidi’s work in order to highlight how Sufi music is used offensively to combat “extreme” forms Islam ( 216), her book does not engage fully with the central argument of Aidi’s work, mainly that music has been deployed for governing Muslims both internally and externally in the form of public diplomacy, counterterrorism and democracy-promotion as early as the end of the Cold War (xxvii), while beginning with the last decade, Muslims have discovered race as a political tool to reinvigorate Islamic thought.

In line with the work of Paul Gilroy, Abdul Khabeer’s work produces embodied knowledge as resisting “the logocentrism that dominates the Euro-American intellectual tradition” (18). She argues that “instead of privileging the word, this practice identifies the body as a site of knowing” (ibid.) Abdul Khabeer’s politics of aesthetics, focusing on embodied knowledge, makes perfectly clear that the body has become a site of contemporary American politics. Muslim Cool is an ethnographic depiction of Muslim life within the United States. In this regard, her work is a most welcome contribution.