When you start studying calligraphy, you never know when you will finish your career. The art of Islamic Calligraphy is a lifelong learning; it is a journey where you don’t just learn how to write letters, but you study some different aspects of human experience such as humility, patience, self-discipline, or “adab” (manners).

I first started making calligraphy after I was attracted to the beauty of the shapes of the letters. I thought to myself, “there is no doubt that exist an arcane, a sacred knowledge, an implicit message hidden behind every stroke and every letter.” To this day, I realize it is the simple fact that there exists a mystery that connects with your soul as soon as you observe a piece of calligraphy even if you can not understand what is written on it. But there is a connection that happens in some different level beyond mere comprehension when you look at a piece of calligraphy. And that connection led me to start practicing calligraphy, making it by myself, with no idea of what I was making, but captivated by the magic of this art form.

Meeting N.G. Masip and Ijazah in Calligraphy

My first meeting with calligraphy came about a few months after I met Nuria García Masip, my future mentor, teacher and the person who originated the biggest professional change in my life. When I met her she already was a renowned calligrapher. She took me to Istanbul and introduced me to her own teachers and so I started studying with her and some of the most important Turkish calligraphy masters. After five years of training, I received my “ijazah” or calligraphy diploma signed by the masters Hasan Çelebi, Ferhat Kurlu, and Nuria García.

Istanbul, the long-term capital of the Ottoman Empire, is a rich culturally and artistically rich city. It is also a place where the tradition of calligraphy has been preserved throughout the centuries. In Istanbul, you can easily find people from all across the world coming to this particular city to learn from the masters.

The teaching of calligraphy was originated in the Arabian Peninsula and quickly ventured into several directions. The main line in the tradition of calligraphy traveled into Syria, Iraq and Persia, and later into Anatolia and the Ottoman Empire. The teaching has been passed down from master to student since the beginning of Islam, creating a chain of knowledge.

The fourth caliph of Islam, Imam Ali, is considered by Muslims as the first major calligrapher. Hence, the chain of transmission begins with him, documented through the centuries until today. That is noteworthy not the least because when you become a disciple in the Ottoman school of calligraphy, you join a chain of transmission of knowledge. It means you have received your knowledge from masters who were once students of older masters, who, to this day, use the traditional teaching methods and the same materials used by the first calligraphers.

“The fourth caliph of Islam, Imam Ali, is considered by Muslims as the first major calligrapher. Hence, the chain of transmission begins with him, documented through the centuries until today.”

At the same time, the fact that the knowledge has been passed down on this way ensures that the classic models or shapes of the letters have not suffered any change. An additional step in preserving the tradition of calligraphy is the observance a series of “rituals.”

Teaching Calligraphy: A Gift

A most important ritual of calligraphy in the Ottoman school concerns the nature of teaching. In this school, teaching has been always considered a “gift,” and that the master teacher cannot charge for this “gift.”

The idea is that, the things we get in life for free are the most important things we get, and when we get them for free we have to give them back for free. That is the essence of the Ottoman Turkish way of teaching calligraphy. It is a gift you receive, the tradition tells us, and one has to give the gift back.

It follows, therefore, that every single calligrapher becomes a teacher because what you get, you give. And when you have the experience, you have to pass it on.

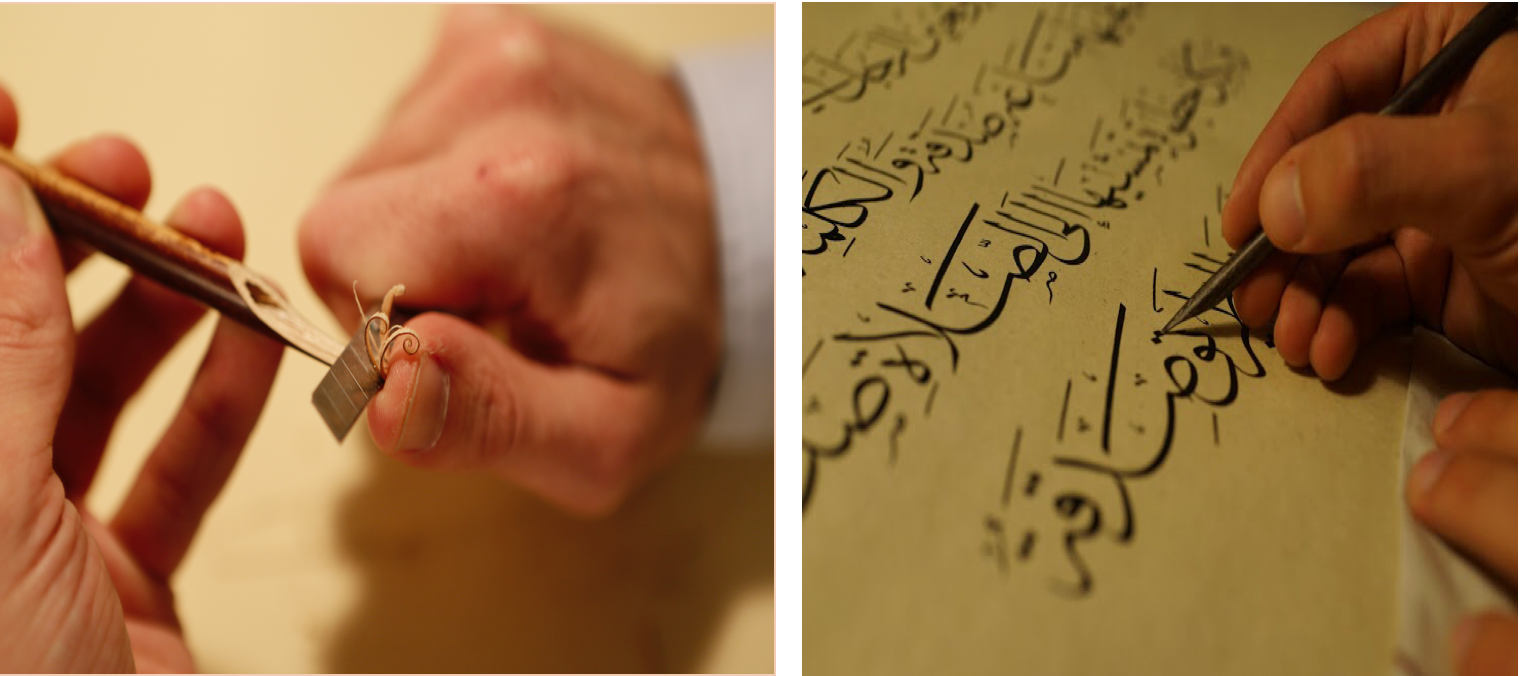

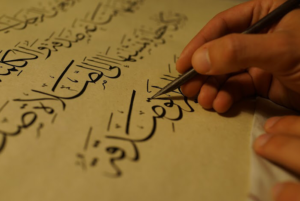

“How the teacher holds the qalam (pen), how he turns it, at what point he starts a stroke, where he pauses and where he finishes it are all aspects of that teacher-student relationship.”

The teaching is always done in person, so the student can see every motion and observe carefully how his master´s hand moves. How the teacher holds the qalam (pen), how he turns it, at what point he starts a stroke, where he pauses and where he finishes it are all aspects of that teacher-student relationship.

The Master’s “Hands”

Every students of calligrapher is taught the saying that reads: “The hand of your master keeps all the knowledge you have to learn.”

The hand has a specific symbolism in this tradition. For a calligrapher, it is very important to have a healthy hand.

There are some interesting stories about master Ottoman calligraphers and their “hands,” such as the story of Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi, who, in addition to being a calligrapher, was the imam of Eyüp Mosque in Istanbul. Every Friday he gave a speech in that mosque and that made him unable to do calligraphy during the day. So, in order to keep his hand from becoming lazy, he kept a small piece of soft material in his hand to exercise calligraphy

Another such story is about one of the greatest calligraphers of all time, Sami Efendi, who used to put his hands in between the buttons of his shirt while walking on the street, in an effort to protect his hands from getting a hit.

In a similar vein, there is an idiom in Turkish language, used often by calligraphers. When somebody has created a beautiful piece of work, they will say “ellerine sağlık,” which means, “may God protect your hands.”

Visit Your Master

Another “ritual” which is constantly repeated in traditional calligraphy circles is that every single calligrapher visit his master weekly to show him his work in order to get corrections and advise.

I mentioned before the fact that the teaching is always done free of charge; so the only way that you have to “pay” your teacher is to apply yourself to this art in the best way you are able to do and never stop visiting him and showing him your work.

And visiting one’s master is not the novice student calligrapher’s responsibility alone, every single calligrapher, doesn’t matter if he is already a renowned calligrapher, should keep up with visits to his master.

“…visiting one’s master is not the novice student calligrapher’s responsibility alone, every single calligrapher, doesn’t matter if he is already a renowned calligrapher, should keep up with visits to his master.”

Your Master is in Your Signature

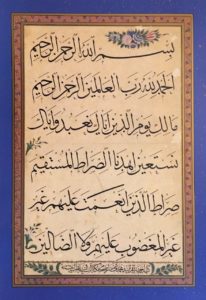

Constant visits are not the only way to traditionally honor a calligraphy master. We , students of calligraphy, honor our masters, through a formula we use to sign a calligraphy piece –this is the same for all the calligraphers. Once a work is completed, with a small qalam (pen) and in the same paper, the calligrapher writes:

[it] was written by the poor (e.g., poor of spirit or humble) – name of the calligrapher –which is one of the students of – name of his master – May God forgive him and be pleased with him.

This formula comes from Hafız Osman, a seventeenth century Ottoman calligrapher. By the time Hafiz was a student, he had already developed a strong talent and he was able to write a copy of the whole Qur’an in a delightful handwriting. One day, his master took this Qur’an and asked Hafız to go with him to visit the Ottoman Sultan of the time so the Sultan could see the beauty of Hafız’s work. The Sultan was fascinated when he saw the copy of the Qur’an, and he inquired from Hafız who was the author of that beautiful work of art., In response, Hafız said: “It was written by the humble student of the master Mustafa Eyyubi.” In other words, just as Hafiz merely mentioned his master’s name to honor and show him respect, in the same way, we, students of calligraphy, follow his tradition to this day.

The Qalam and its Shavings

The qalam we use to write calligraphy might seem like a simple piece of bamboo, but for Muslim calligraphers it has a very special significance and a number of rituals are closely connected to the qalam.

In Muslim literature, we find that the first thing God created was the qalam, and its duty was to record every event that happens in one’s life. Similarly, we find that in the Qur’an “a whole chapter, Surat al-Qalam”, the sixty-eighth chapter, takes its name from the qalam.

We should also keep in mind that the calligrapher spends a great amount of time every day, and during his whole life, with the qalam in his hand, such that the qalam becomes a prolongation of the calligrapher’s hand. A prolongation which is used to express some ideas and feelings on the paper. The qalam, therefore, is the most sacred tool for a calligrapher.

As such, a ritual respected by students of calligraphy is to keep all the shavings you get every single time you cut and sharpen your qalam (pen)Most of what calligraphers write, not everything but most of it, is directly related to Qur’anic verses or Hadiths (teachings from the prophet Muhammad). And this is one of the reasons why we keep the shavings of the qalam; we don’t want to throw a part of the tool we use to write sacred texts to the trash and mix them with garbage.

Therefore, the tradition says that the calligrapher has to keep all his shavings since the day he starts learning calligraphy until the day that he dies. and when death falls upon a calligrapher, his family collects the shavings and puts them to fire in boiling the water they will use to wash the body of the calligrapher (in Muslim tradition, the family is still in charge of the deceased’s body). In other words, when the calligrapher disappears from this world in its material form, the shavings of his qalam also disappears.

The Water and the Ink

Something similar happens with the water we use to mix the ink. During the Ottoman Empire, calligraphers would only use rain water to make their own inks. As they say, rain is “Rahmatullah,” which means “mercy from God.” This is why, the calligraphers considered it the purest water they could use.

Nowadays, as well as rain water, we use rose water or distilled water, in an effort to avoid using tap water. This is because we are not sure if the pipes this water is passing through are completely clean; we don’t want to write something which has a sacred meaning for us with something which might be dirty or not pure enough.

The ink we use is made by soot, Arabic gum and water.In the past, calligraphers used to collect the soot from the oil lamps that illuminate the mosques and use that to make their own inks. The famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, also known as Sinan the Architect, for example, ordered his disciples to build a small room atop the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul during the construction phase. All the soot from the lamps were diverted to this room, where, once a year, calligraphers used to go and scratch the soot pasted at the walls and the roof; they would use this soot in preparing their ink.

The calligraphers would use this ink to write the copies of Qur’an. They would later give these copies to the mosque as a charity. In other words, what originated in the mosque in a soot form, came back later to the same place in a beautiful handwritten Qur’an form and would stay there for a long time.

Tomb Visitation and Calligraphy

Another ritual the calligraphers traditionally observe is to visit the tombs of the great calligraphy masters of the past. In these visits, in addition to praying for the masters’ souls, the calligraphers would bury a qalam at the level of the hands of the person who is buried, and leave it there for some time. Later on, they would come back to the tomb and pick the qalam up to use it for their calligraphy works. It is believed that this qalam will take on some baraka (the blessings or the positive energy from the calligrapher) and it will make the work of the calligrapher easier and beautify the handwriting.

Survival of a Tradition and Making Art

These rituals are not mandatory for all calligraphers, nor are they observed by everyone who is engaged with calligraphy. Nonetheless, in part thanks to these traditions, , as well as some other factors, generations of calligraphers were able to keep the essence of this art alive and those are very important points we have to keep in mind when we talk about calligraphy.

Speaking from my personal experience, it is very much true that all of these traditional aspects really fascinated me and made me fall in love with this art. At the same time, however, there is the practical part, the practice, the creative process where somehow you can express yourself by composing a calligraphy piece.

Creating a piece is a long process where the final result should be like a static theatrical representation where every little thing is carefully placed and has been chosen according to its beauty, balance and flow in relation to the rest of the elements you have in the composition. As my teacher says, “creating a piece of calligraphy is like sculpting a sculpture.” A final piece should be poetry for the eye, should be music written in a paper, a delight for the eye, and should carry a meaning for the soul.

“As my teacher says, ‘creating a piece of calligraphy is like sculpting a sculpture.’ A final piece should be poetry for the eye, should be music written in a paper, a delight for the eye, and should carry a meaning for the soul.”

In my opinion, the first thing one has to keep in mind while he is working on a composition is that this particular piece of work will last in this world (hopefully) for a long time, so we have to be really careful about what we want to leave in this world. In other words, it is the calligrapher’s responsibility to create something good enough to leave with others.

Reaching the “Hal”

When we look at a calligraphy piece, there is a dialogue that happens. This is a non-verbal dialogue, a communion between the geometry of the letters and our own cellular geometry. This make it all the more important because every single artwork is going to have an effect not only on the people who will observe it, but its specific geometric features will also transform the environment of the place where this artwork is exhibited. Somehow, it will transform the atmosphere of that location. This is in addition to the fact that as calligraphers we work with words and it is well known that words have a powerful impact or energy when we pronounce them.

In this piece above by Nuria García, we see a composition where this big letter “ha” stands out. This letter is used by Sufis during their sessions of meditation to reach the “hal,” which is a state of consciousness that is supposed to be in a higher level than the ordinary state and that brings you closer to your being, your essence, and therefore, your Lord.

So, if we understand the words as mantras, these will have a very specific effect on ourselves when we pronounce them. The power of words will have one or another effect depending on how we pronounce them. And the power of the written word, will have varying effects depending on how it is written.

And that is what calligraphers try to do in every single stroke they make. They try to get themselves closer to and discover the future aesthetic which is hidden behind every stroke.