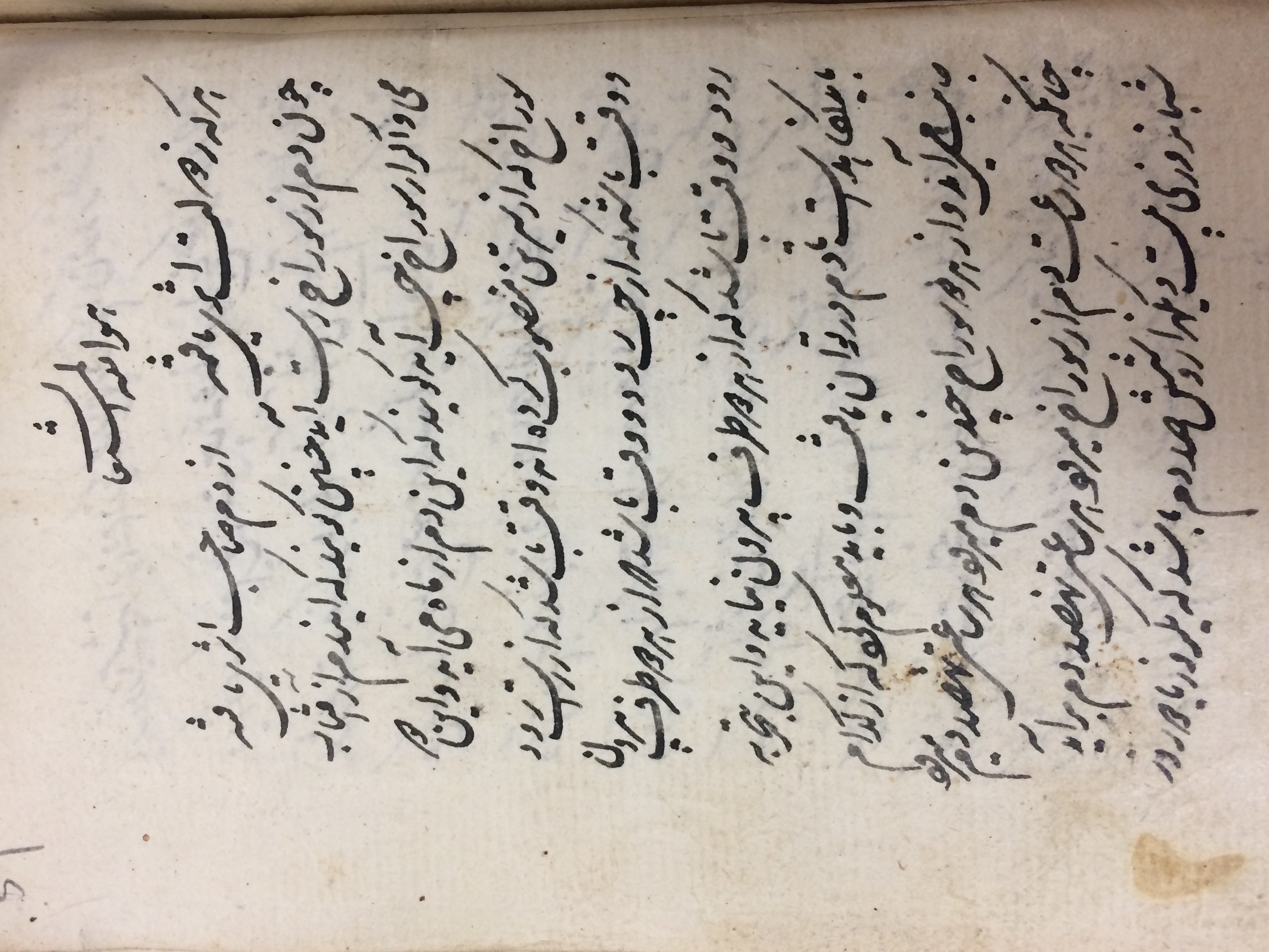

“This is the practice of the yogis. It is not the activity of the people of Muhammad, but it is correct.”[1]

This line, taken from the margins of a mid-eighteenth century South Asian Persian manuscript on using knowledge of the breath for divination purposes, raises several questions for scholars of Islam in particular, and those studying religion more broadly. How do we react when authors from days gone by espouse a very different relationship to religious difference than what many of us unreflexively replicate in our scholarship today? Do we dismiss these words, so painstakingly put to page, or do we take a breath while sitting with our discomfort and ponder what this long-gone person meant?

Engaging “the Science of the Breath”

India’s religious heritage has long resisted the bifurcation of spiritual practice along strictly sectarian lines;[2] an example of this phenomenon is sciences of the breath found in non-Muslim as well as Muslim literature before our modern categories came into place. In recent years, there has been some limited engagement with the translation of yogic texts such as that by Shattari Sufi master Muhammad Ghaus’ Bahr al-Hayat (“Ocean of Life”) into Arabic. For example, Sara Abdel-Latif describes the powerful experience of reading a text whose contents fall outside the folds of Islam as it is constructed in the boundary-obsessed present day, reflecting especially on the response to this type of text by modern-day Salafis.[3]

“How do we react when authors from days gone by espouse a very different relationship to religious difference than what many of us unreflexively replicate in our scholarship today?”What I would like to add to Abdel-Latif’s contribution is that we miss the mark if we think for one second that Ghaus’ work is by any means a one-off, some type of outlier. To the contrary, scholars of Islam and South Asian intellectual history can find a great number of Muslim authors who worked to translate, interpret, and internalize non-Muslim religious and philosophical teachings. The most famous examples of these include the Mughal emperor Akbar (d. 1605 CE) and his grandson, the ill-fated Dara Shikoh (d. 1659). While Akbar is famous for creating his own religious tradition, known as the Din-i Ilahi (“divine faith”) and for debating with representatives of multiple religious traditions in the `ibadat khana (“House of Worship”), Dara Shikoh was very invested in exploring the connections between Sufism and Hinduism, as found in his 1656 CE treatise, Majma` al-Bahrayn (“The Meeting of the Two Oceans”).[4]

`Ilm-i dam in the Indian Landscape

However, beyond the spotlight historically reserved for the actions of emperors and princes, there are numerous texts in Persian and Urdu testifying to the widespread engagement with yoga and other Indian practices. There are several points of origin for these practices. One is a Persian text known as the Kamaru Panchashika (“50 verses of Kamaru”) that is a collection of yogic practices translated into Persian by 1353 CE at the latest.[5] Another is a set of Sanskrit texts known as svarodaya, which exist in the form of dialogues between Shiva and Parvati in which the former expounds on the nature of creation and explains how knowledge of the breath’s flow through channels (nadis) within the body allows one to understand the connection between the micro- and macrocosms.

“…beyond the spotlight historically reserved for the actions of emperors and princes, there are numerous texts in Persian and Urdu testifying to the widespread engagement with yoga and other Indian practices.”In this genre, the breath can be classified according to its connection to the sun or the moon, which in turn maps onto different sides of the body, as well as a combination of the days of the week and the five elements (earth, wind, water, fire, ether). In short, knowing one’s breath is a complicated act that requires a great deal of training and discipline.

Practicing these methods equips one with the ability to know the appropriate moment to travel, go to war, enter into a marriage contract, make friends with enemies, curry favor from one’s rulers, and even predict the moment of death.

In my own work examining texts on the “science of the breath” (Persian: `ilm-i dam),[6] I have identified several variations of `ilm-i dam texts, many of which are six-chapter abridgments of the Kamaru Panchashika, including a fourteenth century encyclopedia,[7] sixteenth century medical compilations from the Mughal royal library, a sixteenth century treatise on Indian knowledge written by Mughal court historian Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak `Allami, a seventeenth century text from Tipu Sultan’s royal library, a nineteenth century Sufi miscellany purchased by Orientalist Edward Granville Browne while traveling in Iran, and a twentieth century version of the text posted on the website of Ayatollah Hassan Zadeh Amoli in Iran.

“In my own work examining texts on the “science of the breath” (Persian: `ilm-i dam),[6] I have identified several variations of `ilm-i dam texts, many of which are six-chapter abridgments of the Kamaru Panchashika…”To be clear, these practices are linked to Sufism in some cases (such as the text Browne acquires as well as Muhammad Ghaus’ Javahir-i Khamsa), but in just as many cases the texts exist in different genres.

How Islamic is ‘Ilm-I Dam?

In a moment that is surely reminiscent of the opening vignette to Shahab Ahmed’s What is Islam?, there are surely some readers asking themselves the question: But wait, how can Muslims practice anything remotely associated with a Hindu god? There are a few answers. A snarky response would read: “Because these Muslims don’t care about sectarian boundaries in the way that us ‘modern’ types do, so fundamentalized have we become,…” A more generous and gentle response would read: “Well, because these are Muslim authors who are less concerned with notions of sectarian purity than they are with pragmatic efficacy.”

“there are surely some readers asking themselves the question: But wait, how can Muslims practice anything remotely associated with a Hindu god? ”That is to say, that these authors (and their readers) include Muslims who have social standing that they must maintain, and part and parcel of protecting (and advancing) their position is accessing all the various types of knowledge at their disposal. In the context of pre- and early-modern South Asia, this means interrogating and incorporating the wide array of practices and ways-of-knowing originally written in Sanskrit that over time are translated into Persian, Hindi/Urdu, and other Indian vernacular languages.

Classification of Texts

Scholars working in the Euro-American academy are constantly dealing with our orientalist legacy, and this includes the ways in which texts have been classified at research institutions. For example, the British Library is home to a massive collection of manuscripts known as the “Delhi Collection,” which is the remnant of what was “acquired” by the British government following the Great Rebellion of 1857 in Delhi. The “Delhi Collection” was a part of the royal Mughal library. Following an initial sale in India in which the most valuable items were snatched up by collectors, the remainder of the collection eventually found its way to London to the India Office Library, which in turn was transferred to the stewardship of the British Library. The Delhi Collection was subdivided by language, hence today one searches through the “Delhi Persian,” “Delhi Arabic,” and so forth.

“The Delhi Collection was subdivided by language, hence today one searches through the ‘Delhi Persian,’ ‘Delhi Arabic,’ and so forth. Of most relevance to the present essay is that there are two `ilm-i dam texts housed within the Delhi Persian collection.”Of most relevance to the present essay is that there are two `ilm-i dam texts housed within the Delhi Persian collection. One is a stand-alone manuscript entitled Rasala dar dam zadan (“Treatise on Breathing”), while the other is part of a larger collection of texts on medicine, entitled Miz al-Nafas (“The Distinguishment of the Breath”). Both date to the sixteenth century. Both begin with the basmala and praise for the Prophet and his family. Both are classified as “Hinduism.”[8]

Boundary Crossing Texts

One does not need to master the mind-reading techniques described in many of the `ilm-i dam texts to imagine that current right-wing political leader of India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his colleagues within his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would have strong feelings about this. And they would not be alone in those feelings, with constituencies from various religious, political, and national affiliations objecting to this manner of boundary crossing textual behavior. Without getting bogged down in the debates over who should be blamed/credited with “constructing” Hinduism, at minimum even casual readers of South Asian history will be aware that there is vigorous debate regarding the extent to which British scholars and officers during and after the colonial period played a part in defining the terms of what Hinduism was and was not.[9]

Orientalist Classification of Texts and Religious Difference

I would add that the dichotomy of definition in this period was not as much between Hinduism and Christianity – although that no doubt played a part – but more so between Hinduism and Islam.[10] These texts on ‘ilm-i dam were classified as “Hindu” because they contained practices that simply could not fit within the British definition of Islam. As Thomas Hughes states in his entry on the Javahir-i Khamsa (“Five Jewels”) of Muhammad Ghaus in the Dictionary of Islam published in 1885: “This book is largely made up of Hindu customs which, in India, have become part of Muhammadanism, but we shall endeavor to confine ourselves to a consideration of these sections which exhibit the so-called science as it exists in its relation to Islam.”[11] Part and parcel of the Orientalist coverage of Sufism is critiquing its Islamic bona fides, minimizing its relevance, and arguing that it has nothing to do with the legalistic rendering of Islam in which the sacred scripture and sayings of the Prophet are the be all and end all of the Muslim “canon.” In the case of Muslim practices in India, writers such as Hughes weave a tale in which Indian Sufism is derivative of Hinduism and Buddhism. This imagining of Sufism (Indian or not) as less Islamic in any way is premised on an ahistorical reading. Contemplating the fact that the reading championed by modern day Salafis mirrors so closely the vision proposed by European colonial officers whose work directly contributed to advancing imperial ambitions to control, colonize, and capitalize on the material resources of Muslim communities requires some deep breathing indeed.

“In the case of Muslim practices in India, writers such as Hughes weave a tale in which Indian Sufism is derivative of Hinduism and Buddhism. This imagining of Sufism (Indian or not) as less Islamic in any way is premised on an ahistorical reading.”

A synthetic reading of the `ilm-i dam corpus proves that these texts circulated widely within Persianate circles in Iran and India for hundreds of years ranging from the pre-modern to the present day. Just as boundaries on a map are constructed, so too are the categories that many of us in the academy use every day in our teaching and publishing. By re-focusing our collective lenses on areas of interlinkage and exchange, those of us in the knowledge-production business can contribute to a broader sense of ecumenism that stands in stark contrast to the current public discourse around religious identity that emphasizes difference at all costs. We give history the short-(sighted)-end of the stick by perpetuating the reductive readings that are largely the product of colonial and imperial discourses.

[1] īn `aml-i jūgiyān ast f`il-i ummat muhammadī nīst līkan darūst ast. Kāmarū Pančāsikā abridgment (Karachi recension), Karachi, N.M.1957.1060/18, f. 2b.

[2] For a brief list of examples, see Anna Bigelow, Sharing the Sacred: Practicing Pluralism in Muslim North India, (Oxford: OUP, 2010) ; Peter Gottschalk, Beyond Hindu and Muslim: Multiple Identity in Narratives from Village India, (New York, OUP, 2000) ; and David Gilmartin and Lawrence, Bruce, Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Identities in Islamicate South Asia, (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 2000).

[3] As Abdel-Latif mentions, Carl Ernst has worked on yogic-sufi exchange extensively. For a collection of his essays on this matter, see Refractions of Islam in India: Situating Sufism and Yoga (SAGE Press, 2016).

[4] For scholars of Islamic mysticism, this phrase is more well-known for referring to the account in Qur’an 18:65-81 of the meeting between Moses and Khizr, in which the former’s mastery of exoteric/zahir knowledge fails to equip him to understand the esoteric/batin motivations for the latter’s actions.

[5] This date is based on the death date of Shams al-Din Muhammad ibn Mahmud Amuli, author of the Nefais al-Funun, a Persian encyclopedia in which an abridged version of the Kamaru Panchashika appears. It is highly likely that the Kamaru Panchashika was written much earlier.

[6] Sometimes the “science of the breath” is paired with “the science of imagination/visualization,” thus `ilm-i dam o vahm.

[7] Amuli’s Nefais al-Funun wa `ara’is al-`uyyun.

[8] I acknowledge that the basmala holds myriad levels of meaning, and that piecing together what one author intends with its presence is difficult across gaps of time and space. However, I would argue that its presence indicates that the author/copyist sought to sanctify this work and saw these practices as part of licit knowledge. That licit-ness is itself an important part of my broader argument on the relationship to religious difference that I see articulated in the various texts within the `ilm-i dam corpus.

[9] Given the growing scholarly literature on the construction of Hinduism as a distinct religious identity, an additional question here would be what we mean precisely by a “Hindu” community. For a few relatively recent monographs on the subject, see David Lorenzen, Who Invented Hinduism? Essays on Religion in History (Yoda Press, 2006); Brian K. Pennington, Was Hinduism Invented? Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction of Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Gavin Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[10] Separating out these two religious traditions – and the communities tied to those labels – was a key component of British colonial rule, an effort that was in turn embraced and appropriated by local factions looking towards a post-colonial future that would appropriate the nation-state as the key currency of modern communal self-determination. The “big bang” resulting from these factors’ collision lead to independence and Partition in 1947, during which the ensuing extent of human suffering surely would give pause to even the most pathological nationalist.

[11] Thomas Patrick Hughes, Dictionary of Islam, A Dictionary of Islam, Being a Cyclopedia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs, Together with the Technical and Theological Terms, of the Muhammadan Religion, (Delhi: Oriental Publishers, 1973), 74. Emphasis added.