Disciplinary fields across the academy are in a state of constant flux, often subject to change and developments at the behest of new theories, scientific discoveries and intellectual innovations. The field of Middle Eastern Studies, spanning across disciplines such as history, political science and sociology often contends with another host of influences dictating many trends in the field. The political environment and international developments play a major role in the types of questions scholars and analysts have pursued, as well as the innovation and employment of new tools of analysis that shed light on the biases that had shaped much of the knowledge in the field just a few decades ago. This knowledge in turn has facilitated new approaches to teaching and engaging students in universities offering courses on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and Islam, and as such present a range of questions pertaining to the pedagogies and curricula in classrooms today. What type of content is being presented, and to what extent has it changed over the years?

Methods and Participants

Data collected from a survey distributed electronically to academics in various disciplines in Middle Eastern Studies suggest insight into some of the trends in teaching in the field. A total of 57 respondents from research universities across the United States answered a series of questions that shed light on topics ranging from content covered in their courses, barriers to teaching in the classroom, as well as the ways in which their own personal graduate training influenced their current teaching and research. A follow up interview was conducted with Professor Zachary Lockman at NYU, an expert on area studies, to gain more nuanced information on how the political environment has created a new sense of urgency in addressing many of the issues that have historically underpinned the field.

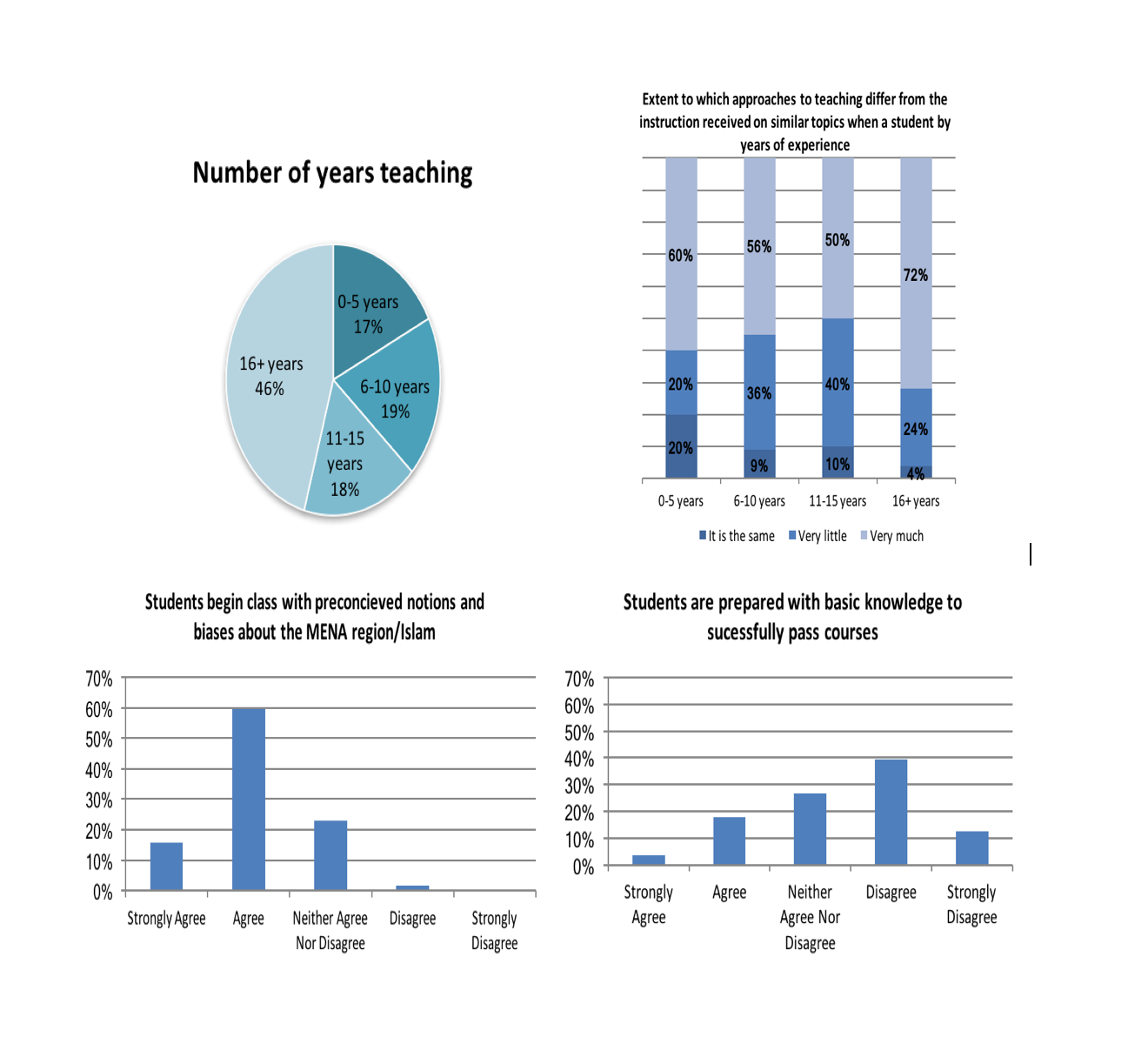

In this project initiated by Maydan, 46 percent of academics reported that they were teaching for at least 16 years, 18 percent were teaching for 11-15 years, 19 percent 6-10 years, and 17.5 percent for 0-5 years. Of these respondents, 33 percent were teaching in history, 38 percent in political science, 14 percent in anthropology and the rest were employed in fields ranging from law, gender studies, architecture and education. For the most part, the majority of respondents (84 percent) report that the era in which their research focuses is the modern period.

“About 40 percent of academics report concerns about the level of preparedness with which their students come into their classes…”About 40 percent of academics report concerns about the level of preparedness with which their students come into their classes, citing they disagree that their students have the basic knowledge about Islam and or the MENA region that would be required to successfully pass their courses. 75 percent of respondents say their students begin their courses with preconceived notions and biases pertaining to the MENA region and/or Islam. At the same time, 33 percent report a peak in enrollment in their courses as Islam and the Middle East become popular topics in public discourse. 48 percent report that they address the biases toward MENA and Islam exhibited in both academia and media to a greater extent in the past few years.

Shifting Trends in Teaching Over the Years

Professors were asked to rate the extent to which their approaches to teaching differed from the instruction they received in their own personal graduate training. Interestingly, the group with the highest degree of reported change/differences was those who have been teaching for the past 16+ years. About 72 percent report changes in their instruction and type of content, in contrast to the 29 percent who cite their approaches were the same are those who have been teaching for 0-10 years.

Some professors report incorporating the use of more data and diverse pedagogy tools in their instruction. One such respondent stated “I use data to present a more ‘objective’ picture of the realities of the MENA region, updating students’ prior assumptions.” Additionally, influenced by the technological developments and increasing accessibility to them, many turn to teaching methods that are more hands on and provide exposure to the region first hand: “I take students to the Middle East for experiential learning. I use techniques such as crisis simulation exercises and other tech oriented innovative teaching methods. The material has substantially changed from when I was in grad school.”

Diversifying Content

Another theme which emerged in the findings of this project suggest that there is now an effort to present information on the “Muslim world.” Furthermore, this effort is more varied, with an emphasis on elucidating “The Muslim world’s” diversity, in contrast to the historical representation of it being portrayed as a monolithic entity: “I place much more emphasis on the Muslim world’s cultural plurality than my instructors did.” Furthermore, more attention is being paid to Islam and Muslims in regions outside of the Middle East, as captured by the following respondent: “…providing broader contextual view on Muslims in different regional contexts. Before, Islam was presented as a singular thing.”

In comparison to their own graduate training, many also report more of an emphasis on historiography and the incorporation of a wider range of works into their syllabi. Alongside the emphasis on broadening students’ understanding of the historical evolution of the writings in the field, some also assign more works by native writers in the field. “I tend to assign many more readings written by persons from the region. I spend time deconstructing and analyzing many Western writings on the region”. This could perhaps be attributed to the growing number of native scholars producing research, but at the same time suggests a growing space for native voices in shaping the field.

In response to the ways in which the training he received as a student differs from his instruction now, Zachary Lockman shares the following:

“ I began graduate study when the critique of Orientalism (and modernization theory, just as big a problem) had just begun to be elaborated — from a Marxian perspective, first, and then by Said and his acolytes. So I’ve always been very concerned to help students understand the intellectual/political frameworks through which questions are posed, objects of study are defined, etc.”

Reconfiguring Old Frameworks

Concerns around these intellectual frameworks were expressed in responses to this survey as well, highlighting the interests and perhaps urgency in creating new paradigms for understanding the region, its cultures and peoples in more “objective” and nuanced ways. For example, one perspective shares “tectonic shifts in world order (not just in the MENA region) require new paradigms in teaching and I am grappling to figure out what the new paradigms should be. It’s a lot more fundamental then whether or not one explicitly addresses bias.”

Some respondents cite they have begun by using “more reflexive or ‘meta’ material looking at biases and challenges of the discipline; more comparative & modern material” as they explore these issues. The need for new frameworks of analysis are important not only for the field itself, but also for political and policy analysts working with the MENA region and Muslim world as well – in an attempt to create policies and dialogue that are more productive and helpful.

With regard to the linkages between the political climate and trends in the field, Lockman also shares:

“My sense is that in Middle East Studies people assimilated the critique of Orientalism long ago; the field has few acolytes of Bernard Lewis, at least in intellectual terms. The current political climate has only heightened our understanding of the need to go beyond the boundaries of academia and find ways to educate wider publics about how (and how not) to think about the Middle East, Islam, etc.”

Citing some specific ways geopolitical developments have resulted in shifts in their curriculum, professors have now begun to place more emphasis on the refugee and migration crises, Arab uprisings, domestic surveillance, ISIL and other current events in courses ranging from history to anthropology. One respondent shares: “ISIS and the war on terror have complicated discussions of Islam, violence. In addition, the notion of a singular ‘West’ is firmly rooted in students’ thinking even after covering Orientalism.”

In response to a similar question posed to Lockman about the ways he has updated his curricula, he shares:

“I don’t teach a course just on Orientalism but address it in the context of how power and knowledge shape one another. I am less likely today to assign students some or all of [Edward Said’s] Orientalism; direct engagement with the text doesn’t always work very well. I more often have them read work that manifests Orientalist thinking, including Lewis, Friedman, Huntington, etc., and help them understand the premises and framework that shapes the author’s perception.”

What Are Some Barriers in the Classroom?

In discussing barriers in teaching in the field, professors cite many common issues that are arguably shared across a wide variety of disciplines. This includes a lack of student preparation and them not being equipped with the tools to properly analyze research, highlighting educational disparities and inequalities pervasive across many educational settings.

“Probably the greatest barrier is student preparedness. My students come overwhelmingly from underserved backgrounds and often do not have reading skills that allow them to understand the reading material I assign.”

The most cited issue that seem to have created problems in classroom discussions was the controversy around addressing the Palestinian question. Professors who were tenured expressed more comfort at covering the topic in class, whereas, those who were not report their inability to address the conflict. Many others also note that students are also reluctant to talk about it as “the Palestine question remains a major problem in the classroom where the presumption of ‘sides’ makes all knowledge impossible” and “a major challenge is that students are reluctant to engage issues in discussion that they know to be controversial. Among them there is also the residual desire to grasp the ‘right’ answer.”

Overall, some circumstances and resources cited for enhancing teaching include the use of translations of contemporary writers from the field to help dispel stereotypes, more exposure on part of students to the region and its culture, supportive department and colleagues, as well as having tenure. Indeed, some of the issues and barriers cited are rooted in wider systemic issues compounding the nature of higher education, though it appears the adoption of new pedagogies and incorporation of new content that also connects with students on a deeper level are in some ways addressing many of the concerns at the classroom level.

Approximately 57 percent of respondents to the survey “strongly agree” or “agree” that they have noticed a peak in enrollment in their courses as Islam and the Middle East become popular topics in public discourse. 84 percent also say that they address the biases towards the Middle East and Islam that are exhibited in both academia and the media to a greater extent over the past few years. These findings suggest that students from a wider variety of backgrounds and majors are enrolling in their courses, and highlight the need to also craft content and instructional styles catering to the diverse needs of students.

As domestic and international politics, coupled with the power of the media, bring the MENA region and Muslim populations and countries across the world into popular discourse in the United States, some educators in higher education are responding with more innovative strategies to address the stereotypes and misrepresentations that shape their students’ views. As Professor Lockman shared, paying attention to orientalism has become common sense for those of us in Middle Eastern Studies. However, outside of our field many are still subject to being exposed to historical distortions, xenophobic ideas, and broad generalizations without the proper tools to deconstruct them. We hope that this survey sheds light onto some of the challenges and recent trends that have shaped the pedagogical approaches to the study of Islam and MENA region.