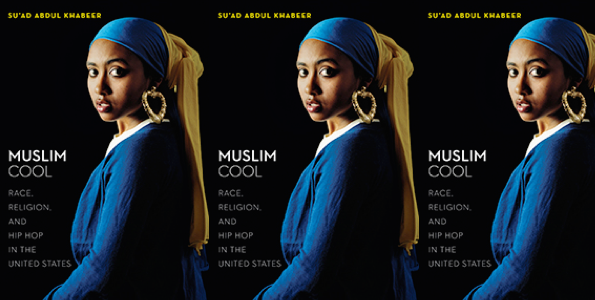

Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States by Su’ad Abdul Khabeer. NYU Press, 2016. 288 pages. $30. Reviewed by Rasmieyh Abdelnabi

Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in the United States by activist scholar artist Su’ad Abdul Khabeer comes at a critical time as U.S. Muslims continue to experience new as well as long-standing challenges. The book has been well received by scholars across disciplines including Aminah Beverly McCloud, Junaid Rana, H. Samy Alim and Marc Lamont Hill and adds to a growing scholarship on Muslims in United States, in particular on the topic of the contributions of Black Muslims to Muslim identity and culture. Abdul Khabeer adds to the growing scholarship with ethnographic research of the multiethnic U.S. Muslim community.

A New Wave of Scholarship on American Islam

Abdul Khabeer’s analysis is in dialogue with the works of several experts on the U.S. Muslim experience. Islamic Studies scholar Sherman Jackson has written extensively about Black Muslims in the United States, whom he terms as “Blackamericans,” in his pioneering book Islam and the Blackamerican: looking towards the third Resurrection (2005). He explores the enduring struggles of Black U.S. Muslims attempting to carve a space in a Muslim community dominated by controlling Asian and Arab traditions. This system dictates that authentic Muslims only come from the so-called Muslim world, which does not include Africa. Another scholar, political scientist Hisham Aidi, has written extensively on the influence of the African-American experience on the Muslim diaspora, arguing that there has been a vibrant exchange among Islamic, Black, and Latin cultures. In 2014, he published Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture, a book on youth culture and musical influences in different Muslim communities in the United States, Europe, and Brazil.

“Abdul Khabeer’s analysis is in dialogue with the works of several experts on the U.S. Muslim experience.”He argues that Muslim youth use music to express their dissatisfaction with government policies aimed at combating terrorism by targeting Muslims. Similarly, African American Studies scholar Suhail Daulatzai writes in his book, Black Star, Crescent Moon (2012), of the shared history between Black Muslims, radical activists, and the Muslim Third World, forging a global connection of resistance. Furthering the discussion on the contributions of Black Muslims in Islam Is a Foreign Country American Muslims and the Global Crisis of Authority (2013) Zareena Grewal, an anthropologist, explores the current debates among U.S. Muslims regarding what it means to be Muslim in the United States and who represents Islam among this diverse population, which includes immigrant and U.S. born Muslims, and Black U.S. Muslims. Abdul Khabeer weaves together her ethnographic work and the existing scholarship on the diverse Muslim community in the United States and Black Muslims contribution to that community, to paint a picture of a changing U.S. Muslim identity she terms Muslim Cool.

An Overview of the Book – Methods, Aim, and Field Site

In her ethnographic account, Abdul Khabeer builds an intersectional narrative using race, religion, and popular culture to demonstrate the ways in which Blackness is central to the construction of U.S. Muslim identity. She argues that Black Muslims were the first Muslims to come to the United States and play a significant historical role in shaping the U.S. Muslim narrative (13).[1] Her study employs the methodological approach of performance studies and ethnography, which she terms performance ethnography and describes as embodied ethnography (18). Using the work of Paul Gilroy, a scholar of African American intellectual and cultural history, literature, and philosophy, Abdul Khabeer describes embodied knowledge as resisting “the logocentrism that dominates the Euro-American intellectual tradition” (18). She explains that “instead of privileging the word, this practice identifies the body as a site of knowing” (ibid.). Abdul Khabeer’s use of performance ethnography includes participant observation and interviews, along with hip-hop performances and lyrics.

“Hip hop, Abdul Khabeer argues, is Islam “because of the long-standing dialogic relationship between hip hop and Islam as practiced in urban Black communities in the United States” (28).”

Hip hop, Abdul Khabeer argues, is Islam “because of the long-standing dialogic relationship between hip hop and Islam as practiced in urban Black communities in the United States” (28). Hip hop artists address issues of self-determination, self-knowledge, and political consciousness among poor and working-class Black and Latinos: “It is a relationship that has constructed an epistemology through which the distinct yet historically rooted set of understandings, self-making practices, and ways of meaning making giving shape to what I call Muslim Cool” (ibid.). In effect, Muslim Cool, is a way of being a U.S. Muslim, as represented in hip hop, ideas, dress, and social activism.

Abdul Khabeer’s ethnographic research was mostly conducted in Chicago, Illinois and centers around the Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN), a community organization that recently opened another branch in Atlanta, Georgia:

“Explicitly committed to antiracist work, IMAN privileges the U.S. Black American experience as a critical site of critique for U.S. Muslims. As the Inner-City Muslim Network, IMAN identifies the locus of its work as the economically resource-poor community of color on Chicago’s Southwest Side, where the organization is located. IMAN’s work in the ‘hood includes not only the provision of services to its poor and working-class neighbors but community organizing with residents around the social and economic justice issues that most affect the neighborhood” (36).[2]

In Abdul Khabeer’s work, IMAN’s inclusion of the Black experience and the centrality of social justice to its mission exemplifies Muslim Cool. She further explains that because of IMAN’s focus on arts-based activism, it has become the “epicenter of the Muslim hip hop scene in Chicago, the wider United States, and even globally,” making it the prime location to conduct her research exploring the influence and reach of hip hop on the U.S. Muslim community (34). Furthermore, the individuals included in her study show the ways in which hip hop counters dominant theories, interpretations, and actions (29).

The Organization of the Book

“Abdul Khabeer coins the term Muslim Cool to describe a U.S. Muslim identity with Blackness at its core, as an alternative to the prevailing identities in the local Muslim communities predominately shaped by South Asian Americans and Arab Americans.”In the introduction and the first chapter of the book, Abdul Khabeer coins the term Muslim Cool to describe a U.S. Muslim identity with Blackness at its core, as an alternative to the prevailing identities in the local Muslim communities predominately shaped by South Asian Americans and Arab Americans (45). Abdul Khabeer argues that Islam in the United States has predominantly centered around South Asian and Arab cultures, offering little space for Black Islam. To further her argument, she uses the work of Sherman Jackson to explore how “Immigrant Islam” dominates the definition of Muslim and the practice of Islam in the United States (12). According to Abdul Khabeer, this is emblematic of racial inequalities within the larger U.S. social structure:

“These traditions of Black Islam share a pointed concern with the realities of Black communities living in conditions of systemic inequality. They respond to conditions of injustice by articulating alternative cosmologies, politics, and social norms geared toward individual and community empowerment” (49).

The loop of Muslim Cool, which is formed through hip hop and Blackness according to the author, calls for activism to counter these racial and systemic inequalities by allowing U.S. Muslims to engage with the knowledge of the self through teachings inspired by Black Islam (74). Engagement with the knowledge of the self is critical to being Muslim because it offers a deeper meaning of Islam, Abdul Khabeer argues (62). She uses the example of a Libyan-American man who grew up Muslim but did not fully understand his faith until he was exposed to hip hop. He came to understand the core of Islam as “knowledge, wisdom, understanding, justice, freedom, equality, love, peace, and happiness” through the Five Percenter philosophy and the loop of Muslim Cool (62). It was through hip hop and by extension Black Islam, that Muslims in the United States are forming a different approach to being Muslim (74).

In the second chapter, Abdul Khabeer discusses pushback by the larger U.S. Muslim community to not include hip hop events or concerts at mainstream events. In addition to the disavowal of Muslim Cool by some in the Black Muslim community, there is also an effort to prove their Muslimness as institutionalized by South Asian and Arab traditions: “It is within this context that Muslim Cool, with its validation and celebration of Black expression culture as an end in itself, offers a counterpoint to the elisions of culture and race that, in the process of policing what is ‘Islamic,’ rehearse the facts of Blackness” (84). Muslim Cool facilitates the inclusion of Blackness in the construction of Muslim identity and breaks down the hegemonic hold that South Asian and Arab traditions have on Islam in the United States (92).

“In the second chapter, Abdul Khabeer discusses pushback by the larger U.S. Muslim community to not include hip hop events or concerts at mainstream events.”

In the third chapter, Abdul Khabeer examines how Black culture helps in the formation of a U.S. Muslim identity. She first examines hijab, or Muslim women’s veiling habits, by looking at the use of traditionally Black or African methods of covering one’s hair by non-Black Muslims. Abdul Khabeer expands on the use of “‘hoodjabi,” which involves a woman covering her hair by wrapping it up in a scarf and creating a bun, leaving the neck and ears uncovered. “While on the one hand the term ‘hoodjabi is a negation of the complexities of Black urban life, hip hop, and Islam, on the other hand Muslim Cool as a lived practice of Muslim identity can be excavated from these associations,” she explains (124). But for Black Muslims “the performativities enabled by Muslim Cool build links of racial sincerity that bridged the disconnect” of an intersectional identity as black and Muslim (129). On the other hand, when it comes to non-Black Muslims’ use of Black or African cultural objects, Abdul Khabeer argues that there is a fine line between appropriation and appreciation: “As a ‘performance,’ Muslim Cool reiterates the definition of race as a social construct that is formed and functions within contexts of power and inequality” (137-138). Appreciation of the use of a hip hop dress style by non-Black Muslims should come with dedicated activism toward ending the racial structures that marginalize Blacks in the United States and within the U.S. Muslim community, otherwise it is appropriation.

“The forth chapter of Muslim Cool looks into the use of stylish dress among Black Muslim men, whom she terms “the Muslim dandy,”…”

The forth chapter of Muslim Cool looks into the use of stylish dress among Black Muslim men, whom she terms “the Muslim dandy,” and the ways in which it is a form of resistance and produces reactions that attempts to disavowal those men as not Muslim or true scholars of Islam. “The Muslim dandy, seeks to confront White, Arab, and South Asian U.S. American supremacies by defining his own priorities. These are priorities of resistance and redemption, grounded in Blackness as a pious and respectable Muslim male style,” she explains.

In the fifth chapter, Abdul Khabeer discusses the employment of hip hop and Muslim hip hop artists by the U.S. government to deliver a message of successful multiculturalism and democracy abroad, but these artists are not given the space to be critical of U.S. foreign policy (213). Muslim hip hop artists use these trips not only to generate needed income, but also to build networks and foster the creation of a worldwide community of hip hop artists (214).

Abdul Khabeer ends the book with a reflection on the Black Lives Matter Movement. She calls on U.S. Muslims to address anti-Blackness within the U.S. Muslim community: “Blackness at the intersection of power and inequality is the contextual backdrop from which Muslim Cool emerges. Muslim Cool is an articulation of Islam, as religious belief and practice, through social justice” (221).

To sum up, Abdul Khabeer’s rich ethnographic work produced a powerful book that sheds light on the immense impact that the U.S. Black community has made and continues to make on Islam in the United States. She sketches a U.S. Muslim identity that transcends race by committing to a much-needed activism that would counter racial inequalities. Black Muslims have been marginalized within the U.S. Muslim community and by making their experiences central, it would lead to the elimination of that marginalization. However, I wonder how Abdul Khabeer would respond to concerns that a call to make Black Islam central to U.S. Muslim identity may be problematic because it prioritizes the narrative and experiences of one group over other groups, which is precisely the current issue with the hegemonic Arab and South Asian narratives and experiences dictating the traditions and customs of the U.S. Muslim community. Furthermore, what does making Black Islam central to U.S. Muslim identity look like? Additionally, I wonder how Abdul Khabeer would have addressed the difficult history and reputation of the Nation of Islam, considering her discussion on the significance of certain teachings of NoI within the U.S. Black Muslim community and NoI’s influence on hip hop artists.

The Conversation beyond the Academic World

“In December 2016, renowned Islamic scholar Hamza Yusuf caused an uproar at the annual Reviving the Islamic Spirit (RIS) Convention, when he criticized the Black Lives Matter Movement.”The U.S. Muslim community combats internal and external struggles triggered by recent events. The election of U.S. President Donald Trump brought with it an intense wave of anti-Muslim rhetoric and action. Within his first hundred days, Trump signed an executive order banning immigrants from six Muslim-majority countries, which halted admission of all refugees and temporarily barred people from Syria, Yemen, Libya, Iran, Somalia, and the Sudan. People across the country swiftly

reacted to the executive order, with protesters flooding airports and various civil liberties groups filing lawsuits against the government. In addition to external pressures, the U.S. Muslim community continues to struggle internally with accusations of anti-Blackness. In December 2016, renowned Islamic scholar Hamza Yusuf caused an uproar at the annual Reviving the Islamic Spirit (RIS) Convention, when he criticized the Black Lives Matter Movement. He attempted to clarify his comments, but many in the Muslim community contend that he should have apologized instead of defending his words. Abdul Khabeer publicly commented on Yusuf’s comments. In a tweet, she stated: “I am highly critical of @hamzayusuf comments on race #RIS2016 & I still benefit from his work. And I know I am not the only one.”

In an interview with ImanWire, a blog produced by Al-Madina Institute, Abdul Khabeer was critical of Yusuf’s lack of apology and his explanation that his comments were not racially motivated:

“I think it’s really really important that we distinguish between intent and impact. And I think what happens often times, particularly within conversations of inequality when people do something, say something that has a negative impact on marginalized people, they say that’s not what I meant. That’s not what I meant and then we all get into this conversation about the nature of the person: they’re a good person, they didn’t mean that. And it’s like no, that’s not relative: what you meant. What we are holding you accountable for is your impact.”

Abdul Khabeer’s comments align with the message of her book, which is to address anti-Blackness in the U.S. Muslim community by creating a more inclusive community that is not only sensitive to racial inequalities and the experiences of marginalized groups, but works to combat inequalities and marginalization.

About the Author

In addition to this book and several academic articles, Abdul Khabeer published a performance ethnography titled Sampled: Beats of Muslim Life, which is a one-woman performance designed to present her research on race and gender, religion, popular culture, and citizenship in the United States. She is also the founder of sapelosquare.com, which is an online publication committed to providing documentation and analysis of the African-American Muslim experience. Abdul Khabeer is currently an associate professor of Anthropology and African American Studies at Purdue University.

[1] For more information on Muslim Africans in the United States visit this page.

[2] Emphasis original.

[3] According to Abdul Khabeer, the Five Percent Nation of Gods and Earths emerged in the 1960s as a spiritual movement by a former youth minister in the Nation of Islam, Clarence 13X or Father Allah. It is a separate movement from the Nation of Islam. On the Five Percenters see, M. M. Knight and Felicia M. Miyakawa.