Charles White, who produced several works about Istanbul in the 1840s, writes about taziyeh ceremonies convened secretly in a derwish lodge, Koca Mustafa Pasa Tekkesi, on the tenth day of Muharram (the first month of the Islamic calendar). Only a quarter century after White’s observations, however, at the end of the 1860s, the Iranian community in Istanbul was comfortable to publicly celebrate the majalis-i rauza khani. In other words, they were commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Hussein without fear. The memoirs of the Western diplomats and travelers as well as the official documents of the time reveal noteworthy information about big crowds, thousands of Shi’a, who gathered for this occasion. Importantly, some of the foreign representatives took their seats to watch these commemorations as guests of the Iranian Embassy.

In addition to these ceremonies which took place at the heart of the capital of the Sunni Caliphate, some other instances of tolerance towards the Shi‘a and their practices continued during the reign of Abdulhamid II (r. 1876-1909) who is well-known with his Islamist policy championing Sunnism. During the later part of his rule, the Ottoman press gave wide coverage to the performance of these rituals too. It was written that during the ceremonies people showed their love and respect not only to the Shah of Iran but also to the Sultan as the Caliph.

It is possible to explain these developments with reference to the Ottoman Empire’s well-known and lenient policies towards different ethnic and religious groups in the post Tanzimat-era. However, these developments were also a consequence of the increasing strength and self-confidence of the Iranian community in Istanbul.

“…it is the nineteenth century when Iranians increased in number and evolved into an active community in the Ottoman Empire, especially in Istanbul”

In his informative study, Bruce Masters examines the changing status of Iranians in the Ottoman Empire after the Treaties of Erzurum, signed in 1823 and 1847. He states that “during any period of its history there were probably more Iranians resident in the Ottoman Empire” than from any other foreign state’s subjects. Likewise, Fariba Zarinebaf shows that some major migration waves from Iran to the Ottoman borders took place in the Islamic era. The first of these waves took place just after the Mongol invasions in the thirteenth century. The second one occurred in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries after the foundation of the Safavid State. Yet, it is the nineteenth century when Iranians increased in number and evolved into an active community in the Ottoman Empire, especially in Istanbul. In other words, the third and the biggest wave occurred in the nineteenth century.

Increasing Numbers, A Widened Network in the Nineteenth Century

Nineteenth century brought a new dimension to the relationship between these two countries. Compared to the conflicts between Selim I and Shah Ismail, or between Suleyman the Magnificent and Tahmasb I in the sixteenth century, relations in the nineteenth century were much more constructive. Different sources argue that this improvement can be explained with reference to the 1823 and 1847 Erzurum Treaties, the opening of the Black Sea to the international trade or the Ottoman Empire’s increasing isolation from the European political system and its defeat in the Russo-Ottoman war between the years 1875 and 1878.

One could add to this list the explanation that when the administrators of both countries became aware of their ineffectiveness against the Western technology and military supremacy, they relied on a new-appreciation of the importance of diplomacy. Therefore, they avoided new problem areas and strived to improve their bilateral relations.

As a result of this, the number of Iranians who went to the Ottoman territory to take part in trade groups, to look for a job, or to pursue travel and education increased gradually. In addition to these factors, some Iranians arrived in the Ottoman Empire on permanent diplomatic missions, or as political exiles and refugees. In this sense, the Ottoman territories, which were physically closer to Iran than Europe, became a better alternative for Iranians. According to Gokhan Cetinsaya, a scholar of Iranian-Turkish relations, Istanbul played the same role for the Iranians which Paris played for the Young Turks.

“…the number of Iranians who went to the Ottoman territory to take part in trade groups, to look for a job, or to pursue travel and education increased gradually.”

As their numbers increased, Iranians in Istanbul started to gather around some specific districts of the city. They lived mainly in the neighborhood on the European side of the city, around and inside some large commercial buildings, called khan. At first, they were resident in khans like Hoca Han, Vezir Han and Sunbul Han, then the Valide Han. For example, the Valide Han housed approximately two thousand Iranians at the end of the nineteenth century. The Iranians were employed in numerous fields such as the carpet, silk, tobacco, leather, and soap trade; as well as in different sectors such as coffee houses, printing, writing, dry goods, and vegetable industries. These Istanbuli Iranians dominated the Istanbul carpet trade with Europe and they rose to the forefront of some fields including cargo, portage and coachmanship. In addition, Iranians in Istanbul were the majority group in certain segments of the labor force. In this context, they mixed with the local citizens more than other foreigners. Some of them even became Ottoman subjects and married Ottoman women despite the prohibition against the marriage of Sunnis to the Shi‘a.

After establishing wide networks within the city, they also opened an elementary school named “Debistan-e Iranian” in the Valide Han. Moreover, they obtained opportunities to have their own social domains and establishments. They expanded the Shi‘i cemetery in Uskudar and founded a hospital alongside a charity organization, named “Bimarkhane-ye Iranian” and “Anjuman-i Hayriyye.”

Akhtar and the Ottoman-Iranian Relations

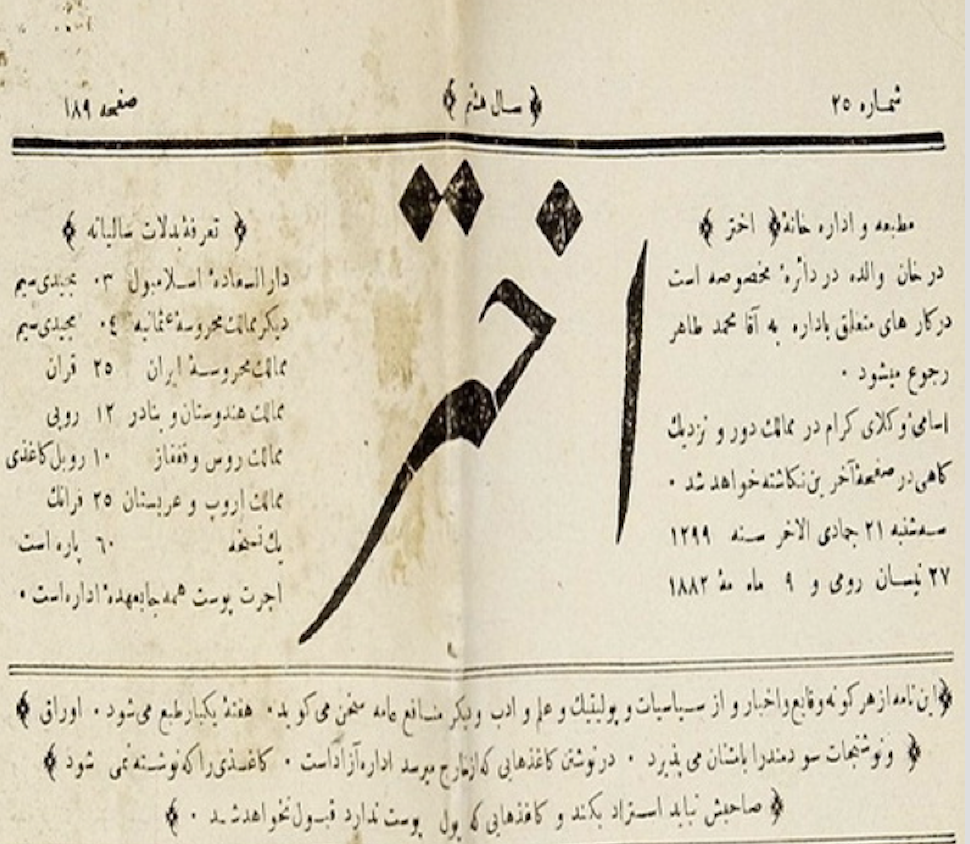

Particularly after increasing of their economic capacity by the 1870s, the Iranians in Istanbul started publishing the first Persian newspaper abroad. In 13 January 1876, a newspaper called Akhtar released its first copy.[1] Akhtar was supported by the Iranian government in the beginning and it avoided political issues. According to Keddie, compared with the Qanȗn, which was also an influential newspaper published by the Iranians in London, during its first decade Akhtar was more moderate in oppositional activities against the Iranian administration.[2] But why did Akhtar become critical of the Iranian government? The answer lies in shifting economic interests as well as experiences with modernity.

We can argue that Iranians in Istanbul experienced and interacted with relatively more modern legal arrangements, establishments, and Western products before their compatriots in Iran. Additionally, as a result of the economic concessions given to the foreigners by the Iranian government, economic interests of the Iranian traders thinned out. Consequently, this community in Istanbul started to demand similar modern benefits for their own country and began to criticize Iranian rulers. Thus, by the middle of the 1880s, Akhtar became one of the focal points of the opposition abroad against Naser ud-Din Shah’s rule.[3] It served as the voice of modernization and calls for reform through the support of intellectuals and exiles like Mirza Agha Khan Kermani, Sheikh Ahmed Rukhi, Malkam Khan, and Jamal ad-Din Afghani.

“Iranians in Istanbul experienced and interacted with relatively more modern legal arrangements, establishments, and Western products before their compatriots in Iran.”

In the meantime, on 20 March 1890, Naser ud-Din Shah granted a concession to an English citizen, Major Gerald F. Talbot. Thanks to this concession, Major Talbot obtained a full monopoly over the production, sale, and export of tobacco in Iran for fifty years. This development led to one of the most important uprisings in modern Iranian history. During the uprising and soon after Jamal ed-din Afghani’s arrival in Istanbul, after which he became a sort of leader of the Iranian community there in 1892, the Akhtar circle started to openly bring up the need for change in Iran and guided public opinion in this direction. To little surprise, Akhtar was suspended in Iran in 1892.

The molding of the public opinion against Naser ud-Din Shah’s rule had continued until the assassination of Shah in 1896 by Reza Khan Kermani who was known for his relationship to Afghani. After the assassination, the Ottoman administration changed its attitude towards Akhtar and the newspaper was closed in a few months. At this moment, the Ottoman administration wanted to avoid any damage to its relationship with Iran and yet this was not enough to prevent deterioration in the bilateral relationship. The killing of the Shah caused tension between the two states because Iranians asked the Ottomans to extradite Afghani claiming that he was the abettor. But, the Ottomans rejected this request due to several reasons: First, they stated that they could locate no evidence about his complicity in the assassination. Secondly, they asserted that Afghani was not an Iranian –as he had himself claimed, Ottomans pretended that he was an Afghan subject albeit his origins from Asadabad, in Iran. As a consequence, the relations between the two countries continued unpleasantly for a while up until Afghani’s death from cancer in March 1897.

From this date onward, Iranians in Istanbul stayed away from the political activities until the first sparks of the Iranian Constitutional movement in 1905. This was somewhat due to the reformist character of Muzaffar ud-Din Shah’s (r. 1896-1906) initial years in power. In addition to reasons including the death of Naser ud-Din Shah and Afghani as well as the closing of the Akhtar, Muzaffar ud-Din Shah’s activities in his initial years led the opposition to remain silent for about ten years.

In the middle of this ten-year period, in 1900, the new Shah visited Istanbul as a part of his first trip to Europe. In Istanbul, he received a very warm welcome and was treated with high-level respect. Ottoman archival documents and the Istanbul press from the time reveal that between the 30th of September and the 4th of October, he was hosted as the most special guest of the Sultan (misafir-i hassü’l-hass). During the Shah’s visit the two rulers presented a very close image that had never been seen in either country’s history. Beginning from the moment he crossed over to the Ottoman border, whenever possible, the Shah declared how happy and grateful he was to be in the Caliph’s lands. According to the October 1 issues of Ottoman newspapers Ikdȃm and Servet, the Shah kissed the Sultan’s hand when they first met. Although this claim is controversial, the close-knit relationship that was on display between the two rulers had influenced the Iranians in Istanbul in their later activities.

“During the Shah’s visit the two rulers presented a very close image that had never been seen in either country’s history.”

Iranians in Istanbul increased their criticisms of their country again in the wake of and during the Iranian Constitutional Movement between the years 1905 and 1909. This well-established and prosperous community succeeded in influencing the Iranian intellectuals who feared persecution in Iran on the eve of the Revolution. Nevertheless, they did not reorganize in real terms until 1908.

In the summer of 1908, the Iranian Parliament was bombed by the order of Muhammad Ali Shah as a part of his coup d’etat. Following this event, the number of Iranian refugees in Ottoman territories increased once again. In June, only a few weeks after the bombing of the Parliament, an organization called Anjuman-i Sa’ȃdat was formed in Istanbul. According to John Gurney, with the formation of this organization, “the first overt political action” was taken against the Iranian rulers. Additionally, the Iranian community endeavored to revive the Persian press in Istanbul. In the same days as the Anjuman-i Sa’ȃdat was formed, Persian newspaper Shams, and in June of the next year, Surȗsh started their short-lived publications.

Conclusion

In some accounts, the emergent activities of the Iranian opposition in Istanbul is linked to the Ottoman Empire’s desire to benefit from such groups, or its wish to influence the Iranian politics by means of the Iranians. In these accounts, it is argued that the main reason behind Ottoman administrations granting permission to the Istanbul-based Iranians’ activities is the Ottomans’ attempt to put the rival Qajar administration in a tight spot. My research points out that these kinds of critics overlook and underestimate the internal dynamics of the community in question. It is true that Iranians in Istanbul found a more liberal environment than their own country. It is also true that having such a trump card against the Qajars would be beneficial for the Ottoman administration. And, the Ottomans indeed took advantage of this dynamic while employing their realpolitik in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

However, these facts do not entirely explain how the Iranian opposition was able to mobilize in Istanbul. The Iranian opposition in Istanbul emerged and later expanded due to the community’s own efforts and in connection to reasons such as the situation in Iran from the beginning of the nineteenth century and the failure of the Iranian administrations to transform the country. Furthermore, it was the political exiles and the merchants who were at the forefront of the community. The first of these two groups had voluntarily immigrated to Istanbul or had been expelled because they chose not to compromise with the Iranian administration. Hence, involvement in dissident activities was a natural course for them. As for the second group, the merchants, they created their oppositional identity following the dissolution of their economic interests.

Just as in the period between 1896 and 1905, when the community hoped that the Iranian government would meet their expectations, and/or, when the government gave some signs of reform, they remained more silent. But, after experiencing further disappointments, they restarted their activities. In other words, the brief trajectory of Iranian community in Istanbul presented here suggest that oppositional activities of them must be linked with their economic interests, social and cultural demands, or political standing against Iranian rulers.

[1] It is possible that another paper called Torkestȃn may have been published a couple of years earlier for a short time. However, information about this paper is very limited.

[2] Nikki R. Keddie, Qajar Iran and the Rise of Reza Khan: 1796-1925 (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 45.

[3] Other than major Ottoman cities there were of course some other places that became major Iranian population centers and sites of dissident activity. For example, Iranians had also increased in numbers in London, Cairo and Kalkuta. They owned opposition instruments in these locations. Egypt was another attractive country with free enterprise and liberal-cosmopolitan atmosphere. In 1882 about 400 Iranians were living in Cairo. About ten years later, in 1892, this number increased to nearly 1300. According to Egyptian statistics, in 1907, there were 1385 Iranians in the country. In Egypt, newspapers such as Hekmat, Sorayya, Parvaresh, and Chehrenamȃ were published by the Iranians during these years. For more information on this subject see, Anja W. M. Luesink, “The Iranian Community in Cairo at the Turn of the Century”, in Les Iraniens d’Istanbul, Th. Zarcone and F. Zarinebaf (Eds.), Paris-Teheran-Istanbul, (IFÉA/IFRI, 1993),pp. 193-200.