In the late 1990s, I arrived in London to begin my PhD after several years of living in the Middle East and South Asia. Registered at the School of Oriental and African Studies, in my free time I delighted in following trails that led back from London to Islamic Asia: Yemeni social clubs, Pakistani eateries, Persian bookstores, or the British Asian clubs and galleries that were burgeoning at that time. To a large extent, I took all of this for granted. Having grown up in a region of Britain that had seen a good deal of immigration from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean, the vivid ethnic and religious variety of London’s streets appeared to me the natural state of affairs, a multiplied effect of the provincial pluralism of my childhood. Only when I hosted a friend from Yemen, who was alternatively amazed and dismayed at the range of Muslims and other peoples on the city’s streets, did I belatedly recognize that London’s diversity is far fro m an inevitable or commonplace state of affairs. After all, there is probably no capital city in the world that has experienced so enduring, intense and layered a pattern of globalization.

m an inevitable or commonplace state of affairs. After all, there is probably no capital city in the world that has experienced so enduring, intense and layered a pattern of globalization.

Yet, as many theorists have pointed out, globalization is uneven and patchy. While it occurs intensely in some places, it remains barely noticeable in others. This is all the more true in terms of its social dimensions of population movement and human interaction rather than in the distribution of commodities and other less visible economic operations that affect even the most remote villages of Africa. While never fully separable from economic forces, the social dimensions of globalization tend to cluster together – as community-building humans invariably do – to direct the human traffic of globalization towards particular urban hubs. Increasingly, such ‘global cities’ have become the focus of sociologists, political scientists, urban planners and security advisers, since they break down many of the fundamental features of the city that were taken for granted in the ages of nationalism and controlled Cold War internationalism.

Historians too have much to add to our understanding of this patchy and clustered form of globalization. In fact, the recognition that globalization is both intensely sited and deeply social – that it thereby has context and contingency – favors the kinds of analysis in which historians specialize.

“In fact, the recognition that globalization is both intensely sited and deeply social – that it thereby has context and contingency – favors the kinds of analysis in which historians specialize.”But if a great deal of historical scholarship has debated the timelines of globalization – the ‘when?’ question – historians have only more recently undertaken case studies of particular global cities to explore the specific contributors and outcomes of specific globalizations. In my book Bombay Islam, for example, I traced the rise of Bombay as the urban hub of an oceanic and imperial mode of globalization. My own research trips to Bombay forcefully confronted me with another well-known aspect of globalization: that it is not only patchy but also reversible. As symbolized by its new official name, ‘Mumbai’ has become much more locked into its

regional and national geography than into the maritime geography and population movements of a century earlier.

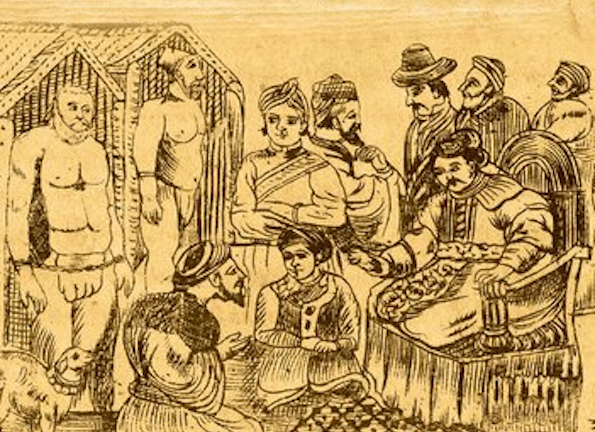

My aim in studying Bombay (as all of my various language sources called the city) was not only to look at the modalities of globalization in a particular place. It was also to look at the experience and, moreover, impact of globalization on a particular community, or rather, a particular cluster of communities: the diverse Muslim populations who settled in or passed through the port. Since Bombay had never seriously been considered either as a Muslim city or as a contributor to Islamic history, in making my selection I was keen to make the point that the Muslim experience of globalization can happen in the most unexpected places.

“Since Bombay had never seriously been considered either as a Muslim city or as a contributor to Islamic history, in making my selection I was keen to make the point that the Muslim experience of globalization can happen in the most unexpected places.”Indeed, one might extrapolate a larger point that the forces of globalization have greatest impact on peoples and in places where they are least expected.

By looking at source materials in both Indian and Middle Eastern languages, I tried to uncover ‘internal’ responses to globalization that would help me gauge not only its impact on Muslims but also on Islam. By borrowing from sociology a model of ‘religious economy,’ I argued that the clustering of populations, communication technologies an transportation in Bombay combined with new ideologies of religious freedom (from the colonial state) and religious competition (from transnational missionary groups) to help create new ‘religious firms’ who adapted their services to the demands of Bombay’s diverse Muslim population base. By showing how the actual content of ‘Islam’ was constantly reshaped in the encounter between transnational religious suppliers and the local communities of migrant workers and merchants who made up the demand side of the religious economy, I hoped to make a robust case for the permeability of religion to global historical forces. And, by capturing the contingency of religious ideas and practices, I also tried to delineate a particular cultural and regional profile of globalization.

By highlighting that the outcome of this intense (and unexpected) Muslim experience of globalization was the proliferation of new religious ‘firms’ – and thereby the production of a dizzying range of new religious leaders, communities and behavior – I also wanted to intervene in debates on the profile and trajectory of ‘global Islam.’ In the conclusions to Bombay Islam, I therefore made a more general case for the diversifying as opposed to homogenizing effects of globalization. Where some commentators have offered a picture of increasing religious standardization, my own research led me to theorize an increasing fragmentation and diversification of Islam (an issue I subsequently took up in another book, Terrains of Exchange: Religious Economies of Global Islam). As the globalization of modes of communication offers more and more individual Muslims access to the means of religious production, I argued that we will find more and more self-appointed leaders, organizations and doctrines each claiming to represent the single true Islam. Collectively, the picture has not only been increased fragmentation, but also, by the late twentieth century, a more violent intensification of the inter-Muslim competition I saw as a response to the more limited globalization of nineteenth century Bombay.

By highlighting that the outcome of this intense (and unexpected) Muslim experience of globalization was the proliferation of new religious ‘firms’ – and thereby the production of a dizzying range of new religious leaders, communities and behavior – I also wanted to intervene in debates on the profile and trajectory of ‘global Islam.’ In the conclusions to Bombay Islam, I therefore made a more general case for the diversifying as opposed to homogenizing effects of globalization. Where some commentators have offered a picture of increasing religious standardization, my own research led me to theorize an increasing fragmentation and diversification of Islam (an issue I subsequently took up in another book, Terrains of Exchange: Religious Economies of Global Islam). As the globalization of modes of communication offers more and more individual Muslims access to the means of religious production, I argued that we will find more and more self-appointed leaders, organizations and doctrines each claiming to represent the single true Islam. Collectively, the picture has not only been increased fragmentation, but also, by the late twentieth century, a more violent intensification of the inter-Muslim competition I saw as a response to the more limited globalization of nineteenth century Bombay.

All this raises the question as to how unique or unusual a set of processes were those I traced in Bombay Islam? For me at least, one of the lessons of my research was that the Muslim encounter with globalization could happen in unexpected places, places which are not even conventionally considered to be part of the ‘Muslim world.’ Moreover, by looking at different Muslim responses to globalization, I also began to see patterns of religious activism in which the tools or opportunities of globalization were used for particular ends. Here was a set of dynamic social processes and private activities rather than a picture of passive subjection to large-scale forces. Global cities in turn began to appear differently to me. Globalization allowed new Muslim hubs such as Bombay to serve not only as religious reception zones that imported Muslims, but also as religious production centers that exported Islam. The geographies and ‘homelands’ of Islam could change, then, in the modern period just as they had in the middle ages.

“Muslim intellectual engagement with Europe produced a new Muslim ‘spacetime’ by way of radically new conceptions of the history and geography of Islam. The very idea of a ‘Muslim world’ was one of these new conceptions of spacetime.”

If all this could happen in nineteenth century Bombay, I began to ask whether similar developments also occurred in certain European cities of the period. Was there, in other words, a prehistory to the increasing worldwide influence that social scientists such as Olivier Roy and Jocelyne Cesari have seen European Muslim communities having since the late twentieth century? In response to this question, I began to look at the migration of Middle Eastern and South Asian Muslims to Western Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. In Terrains of Exchange, I argued that European sites of M uslim globalization such as London, Paris and Berlin did indeed become production and export centers of Islam. As in the case of Bombay, the new ‘Islams’ that were exported from these European cities were the contingent creations of their specific contexts, contexts which inevitably produced culturally hybridized religious forms. As I conceived the matter, Muslim intellectual engagement with Europe produced a new Muslim ‘spacetime’ by way of radically new conceptions of the history and geography of Islam. The very idea of a ‘Muslim world’ was one of these new conceptions of spacetime.[1]

uslim globalization such as London, Paris and Berlin did indeed become production and export centers of Islam. As in the case of Bombay, the new ‘Islams’ that were exported from these European cities were the contingent creations of their specific contexts, contexts which inevitably produced culturally hybridized religious forms. As I conceived the matter, Muslim intellectual engagement with Europe produced a new Muslim ‘spacetime’ by way of radically new conceptions of the history and geography of Islam. The very idea of a ‘Muslim world’ was one of these new conceptions of spacetime.[1]

In my most recent book, The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen’s London, I decided to move back to the global, Asian and Islamic London that I knew as a student, albeit seeing it through the eyes (or rather, the diaries) of the first group of Muslims to study in the city two hundred years ago. By looking at the social networks that Mirza Salih Shirazi and his pioneering companions negotiated in the London of the 1810s, I hope to bring to light an important but all-too-neglected aspect of globalization: the friendships forged between Muslims and non-Muslims. Whether in terms of religious homogeneity or clashes of civilizations, there is nothing inevitable in the trajectories of globalization.

*This article was originally written in 2013.

[1] Nile Green, “Spacetime and the Muslim Journey West: Industrial Communications in the Making of the ‘Muslim World,'” American Historical Review 118, 2 (2013) and, Terrains of Exchange.