In January 2013, France launched Operation Serval, a military intervention designed to restore the territorial integrity of Mali. The operation was meant to dislodge a coalition of jihadist groups that had ruled northern Mali for much of 2012. These groups included Al-Qa‘ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and several of its allies. Operation Serval soon recaptured most of the north.

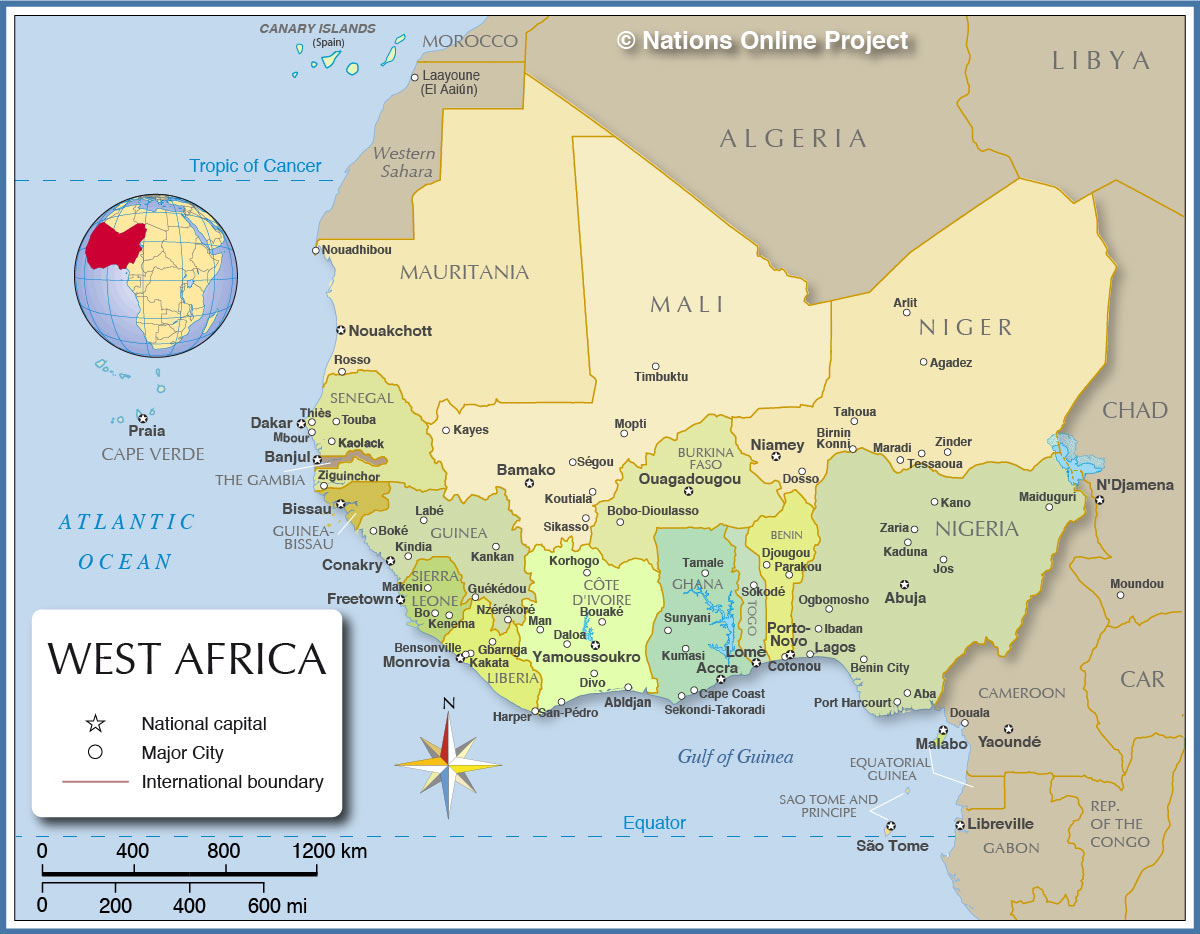

Mali’s neighbors experienced the effects of the crisis in myriad ways, from refugee flows to security concerns. One heavily affected neighbor was Mauritania. Since the 1990s, Mauritanian heads of state have taken strong rhetorical and military stances against both real and perceived Islamic militancy in their sub-region. From 2005-2011, Mauritania also became a theater for attacks by AQIM. The group raided army outposts, kidnapped Westerners, and attacked foreign embassies in Mauritania. Current Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abd al-Aziz, who came to power in a 2008 military coup and won election as a civilian in 2009, made fighting AQIM a top priority. For reasons that remain unclear – perhaps due to counterterrorism successes, and perhaps due to a secret truce – AQIM’s attacks on Mauritania slackened around the time that Mali was disintegrating.

Ould Abd al-Aziz has had a complex relationship with Mali, especially in terms of counterterrorism. Before Mali’s most recent civil war, Mauritanian leaders felt that Mali was flirting, dangerously, with appeasement: in 2010, when Mali’s government agreed to exchange AQIM prisoners for European hostages, Mauritania and Algeria withdrew their ambassadors in protest. In 2010 and 2011, Mauritania took its fight against AQIM into Malian territory, fighting AQIM on the border and hunting and bombing AQIM inside Mali.

When AQIM became a key force within the jihadist coalition in Mali’s north, Mauritania felt its own interests threatened. Yet throughout 2012, as West African and Western governments explored the possibility of mounting a military intervention in northern Mali, Ould Abd al-Aziz expressed unwillingness to join the campaign. Ould Abd al-Aziz eventually acted as one mediator between the Malian government and Tuareg separatists, but Mauritania avoided the kind of open and sustained military involvement made by another Sahelian country with regional leadership ambitions, Chad. Mauritania also declined the extended diplomatic commitment made by Burkina Faso. Mauritania’s ambivalence toward Operation Serval merits analysis.

The Mauritanian government’s reluctance to intervene in Mali may have partly resulted from domestic discourses, including ones that portrayed the Western-led intervention as part of a global assault on Islam. There is precedent for Muslim voices swaying the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania: after a decade of anti-Israel protests by Islamist activists, Ould Abd-Aziz suspended relations with Israel in 2009. Islamists have also urged Mauritania’s government to pursue counterterrorism without accepting help from non-Muslim states like France.

We can gain some insight into the domestic pressures Ould Abd Al-Aziz faced by examining a fatwa (legal opinion) entitled Haqiqat al-Harb ‘ala al-Muslimin fī Shimal Mali (The Reality of the War on Muslims in Northern Mali). During the French-led war in Mali, the fatwa circulated on the internet as Fatwa ‘Ulama’ Shinqit Hawla Mali (The Opinion of Muslim Scholars of Mauritania Regarding Mali). The text shows that some Mauritanian scholars stood ready to harshly criticize their government should it assist in external military interventions in Mali. These scholars did not speak for the Mauritanian masses, nor did they represent the country’s top scholars – but they pointed to the possibility of a wider anti-Serval feeling emerging among Mauritanians. Regionally, the scholars’ words resonated even after the formal end of Operation Serval in 2014. When the Malian jihadist leader Iyad Ag Ghaly resurfaced in a video in August 2014, he cited the Mauritanian fatwa as part of a diatribe against France’s military involvement in Mali and beyond, saying, “Islamic legal obligation (al-wājib al-shar‘ī)…impels us to confront this barefaced hostility (al-‘udwān al-sāfir) with all the strength we are given.”

“The text shows that some Mauritanian scholars stood ready to harshly criticize their government should it assist in external military interventions in Mali. These scholars did not speak for the Mauritanian masses, nor did they represent the country’s top scholars – but they pointed to the possibility of a wider anti-Serval feeling emerging among Mauritanians.”

The Fatwā: Framing Mali’s Crisis as Part of a Global Islamic Struggle

Fatwā ‘Ulamā’ Shinqīṭ Ḥawla Mālī used conventions of the fatwa genre to portray the crisis in Mali as a religious phenomenon. Many fatwas begin by lauding God and the Prophet Muhammad, a convention that creates room for introducing core themes. In its opening lines, the Fatwā framed the conflict in Mali as a choice between injustice and solidarity: “Praise to God who forbade injustice and enmity, and ordained justice and mutual aid between brothers.” Many fatwas invoke Qur’anic verses as textual support for legal rulings. The Fatwā on Mali quoted passages encouraging Muslim unity, such as Qur’an 49:10: “The believers are but a single brotherhood, so reconcile your two brothers, and fear God, that you may receive mercy.”

Building on this introduction, the Fatwa framed the conflict in northern Mali as an effort by “the enemies of the religion (‘adā’ al-dīn)” to “occupy northern Mali (iḥtilāl shimāl Mālī).” Muslims, the Fatwā continued, must “know their obligations and carry out their responsibilities towards this land and its people.” The Fatwā cited other fatāwā from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries ruling against Muslims aiding non-Muslims in armed conflicts.

The Fatwā framed the conflict in northern Mali not only as an anti-Islamic occupation, but also as part of a global pattern. The war in Mali was “only an extension of a series of colonialist campaigns” in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, and Somalia. Together, the Fatwā explained, these efforts seek to impose “the new world order (al-niẓām al-‘ālam al-jadīd)” with the ultimate aim of separating Muslims from their religion. Here the Fatwā referenced Qur’an 2:217: “And they will continue to fight you until they turn you back from your religion if they are able.”

In the eyes of the Fatwā’s authors, supporting a Western-led (i.e., infidel-led) military intervention in northern Mali would violate the unity that is essential to the preservation of Islam. In this context, the Fatwā referenced the doctrine of al-walā’ wa al-barā’ (“loyalty to the believers and disavowal of the unbelievers”), which emphasizes loyalty to the Muslim community in exclusive preference to partnerships with non-Muslims. The doctrine of al-walā’ wa al-barā’ is often a core theme within jihadist circles.

The Fatwā did not address the Mauritanian government or make formal recommendations concerning its foreign policy; rather, the text asserted obligations and responsibilities that Muslims have toward other Muslims. Nevertheless, the authors spoke as Mauritanians. At several points, the text stated that Mauritanian Muslims have a special duty, given their proximity to Mali, to show solidarity with the Muslims of Mali. Invoking the idea of Islamic solidarity implied that the government of Mauritania, officially an “Islamic Republic,” should not endorse or participate in any Western-led military operation that might harm Muslims in northern Mali. The Fatwā, appearing just days after Operation Serval began, seemed aimed in part at the government. In this sense, the text fits within a broader context of Islamic discourses in Mauritania that have attempted to influence the government’s foreign policy.

The Fatwā appeared in online fora and received coverage in the Mauritanian press. Thirty-nine Muslim scholars signed it, identifying themselves variously as imams, du‘āt (singular: dā‘iya, or one who calls people to Islam), teachers in maḥāẓir (singular: maḥẓara, a type of school for advanced Islamic education in Mauritania), and in one case a mufti or jurisconsult. Some of the signatories participated in earlier actions directed at the Mauritanian government, such as a 2012 petition calling for the release of Salafi prisoners. Well-known signatories included Mohamed Salem Ould Mohamed Lemine al-Majlissi, a jihadist thinker repeatedly arrested and detained by Mauritanian authorities in connection with AQIM attacks. Al-Majlissi was acquitted of terrorism charges in July 2012 after spending over seven months in prison. If the government had hoped to secure al-Majlissi’s silence by acquitting him, the Fatwā showed his continued willingness to comment on politics and conflict in Mauritania and beyond.

The Fatwā cannot be said to represent the opinion of the majority of Mauritanian Islamic scholars, nor does its list of signatories contain the country’s most prominent religious leaders. Nonetheless, it conveyed the stance of some Mauritanian Muslims, particularly hardliners. By attaching their names to the fatwa, the thirty-nine signatories also signaled their willingness to preach an anti-Serval message from their various platforms – mosques, schools, and courts – should the Mauritanian government join the operation. Their stance cannot have been the only factor that brought Ould Abd al-Aziz to limit Mauritania’s participation in Operation Serval, but the Fatwā may have contributed to that decision.

Conclusion

Since the formal end of Operation Serval in 2014, northern Mali has suffered chronic guerrilla attacks by jihadists. Despite various peace accords, a meaningful political settlement has proven difficult to build. Tensions persist not only between the government and armed groups, but also among the armed groups. For the government and many of those groups, jihadists are anathema. Jihadists have never been included in formal peace talks, but at times it seems difficult to see how northern Mali can have peace without some settlement involving the jihadists.

“More than ever, Muslims in Mali, Mauritania, and the broader Sahel region live in an environment where a host of actors compete to speak for Islam.”

A meaningful “religious settlement” is also missing. More than ever, Muslims in Mali, Mauritania, and the broader Sahel region live in an environment where a host of actors compete to speak for Islam. The fatwa discussed here exemplifies that process. Figures such as Mauritania’s al-Majlissi, a key signatory to the fatwa, do not speak for more than a sliver of Sahelian Muslims, but their words carry weight with enough people to be politically significant. In other words, the presence of hardliners shapes the political space available to Sahelian policymakers. As Mali attempts to move forward, policymakers there would be well-advised to keep an ear to the ground in order to make sense of the various religious messages that Malian Muslims may be hearing. It would be unwise to cater to the hardliners, but it would be equally unwise to view them only as a military problem.

For their part, Mauritanian authorities have sometimes seemed to listen, begrudgingly, to the hardliners. Such decisions may have forestalled broader domestic discontent at sensitive political moments. Mali’s path forward will be harder than Mauritania’s, but Malian authorities might benefit from studying Mauritania’s own recent history with religious hardliners as they continue to chart a way to deal with similar, if not the same, problems.