Editor's note: Over the next few weeks Maydan will publish articles presented at the Sectarianism, Identity and Conflict in Islamic Contexts: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives conference held at George Mason University in April 2016. We hope this series will help the broader public to develop a healthier engagement with the concept of sectarianism, an often misunderstood phenomenon.

The study of what has ostensibly come to be known as “sectarianism” owes its epistemological underpinnings to power-laden discourses implicit within Orientalism. While the concept’s dubious origins come as little surprise to us as post-Saidian subjects, its continued use in the fields of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies in spite of its questionable utility for understanding conflict and violence in places and among people where Islam predominates merits reconsideration. As one of the basic hallmarks of Orientalist framing of the manifold articulations of Islam that they encountered in pre-modern literary sources (e.g. chronicles, biographical dictionaries, theological and legal treatises etc.), the earliest European and later North American scholars of Islam perfunctorily utilized the theological language and categories of church history as grounds for inquiry into non-Christian religion. The “sect”, “church”, “denomination”, “cult”, typology lent itself quite easily to the very sources that late nineteenth and early twentieth century Orientalists availed themselves of to study religious and ethnic difference among Muslims. The principal sources used by these scholars were predominately Sunni chronicles and heresiological literature and it is these sources that continue to frame the master narrative concerning the origins and development of both Shi‘ism and Sunnism – largely without critical attention to their inherently polemical and perspectival dimensions.

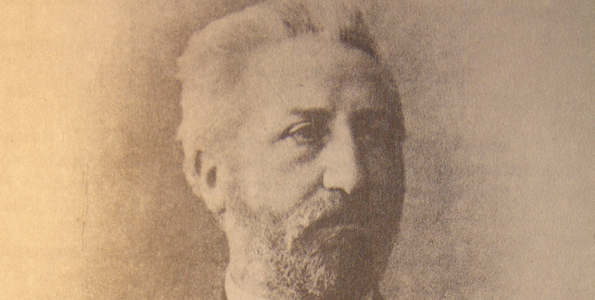

On the basis of the Sunni sources that initially caught the attention of the Orientalists it would seem almost intuitive to regard the perspective of their Sunni informants as corresponding to “orthodox” church Islam, and the Shi‘i point of view as that of a “heterodox” sect. One of the first Western scholars to address the nature of Shi‘i religious beliefs and practices, the late nineteenth century Orientalist, Ignaz Goldziher, in fact classified as a “sect” in the Islamic context any group that “depart[s] from the sunna, the historically sanctioned form of Islam, on essential issues of fundamental importance for all Islam, and who on such issues contradict the ijma.”[1]

Perhaps in part as a result of the theological predilections and analytical categories employed by the founding fathers of the academic study of Islam, over one hundred years after Goldziher published his text, many contemporary scholars of Islam continue to rely upon Sunni polemical sources and heresiographies for situating Shi‘i-Sunni religious differences. In addition, the reliance on largely hostile Sunni sources, and heresiographies in particular, may lead one to overestimate the importance of the ghulat or more extreme elements among the Shi‘a, whose views are hyperbolically given far more attention in heresiographical sources than they are likely to have had among their contemporaries (even in the context of fitna and firāq literature originating in the late first century and proliferating by the middle and later second century). In fact, Goldziher refers his readers to the heresiographical literature for “proofs that Shi‘ism was a particularly fecund soil for absurdities suited to undermine and wholly disintegrate the Islamic doctrine of God.” Such statements by non-Muslim Orientalist scholars necessarily begs the question of why one with seemingly no particular doctrinal or dogmatic investment in polemical discourse would engage in this form of exposition?

“The Orientalist legacy of the “church”, “denomination”, “sect”, “cult” paradigm inherited from scholars of Christianity carried with it the geographical and conceptual centering of what these scholars considered to be rational religious discourses within their own social and religious context and projected their predilections onto their emerging historiographical tradition.”The Orientalist legacy of the “church”, “denomination”, “sect”, “cult” paradigm inherited from scholars of Christianity carried with it the geographical and conceptual centering of what these scholars considered to be rational religious discourses within their own social and religious context and projected their predilections onto their emerging historiographical tradition. Their mode for evaluating primary source narratives followed a simple logic of privileging what was commensurate or divergent from distinctions that emerged within a Christian milieu, with Shi‘i sources viewed in a more critical fashion due to what was thought to be their inherently heterodox “sectarian” concerns. Perhaps more problematic was the selectivity of the Orientalists in editing manuscript works that mirrored their own predilections and hierarchical conceptions. These literary sources, primarily Sunni chronicles and biographical dictionaries, were thought to represent the high points of the historiographical tradition and ultimately came to form the canon for Orientalist scholarship on Islamic and the Middle Eastern history.

This is not to suggest that our contemporary understanding of religious difference among Muslims is solely the product of the religious and political concerns of Orientalist authors and their historiographical frameworks. However, it is clear that the legacy of Orientalist framing of, and nomenclature for, religious and ethnic distinctions among Muslims is empirically and conceptually inadequate to be useful for critical interpretation of pre-modern Arabic and Persian primary sources and secondary literature. It is also notable that the normativizing language of “churches” and “sects” effaces much more than it discloses even as an explanation for the development of early Christian history itself. This typology is even less relevant to “non-Christian regions” and religions as a model. It is also of some significance that the perverse logic of the application of “sectarianism” as a crude typological appendage to what Orientalists understood to be taking place during the formative period of Islam lead some scholars to without irony consider the Shi‘is to in fact be the “Christians of Islam” or even go as far as categorizing various Shi‘i groups as crypto-Christian.

Perhaps here I am partaking in the low hanging fruit to point out that in describing what he considered the “sectarian” movement that culminated in the development of various Shi‘isms, Bernard Lewis states rather prosaically and in his characteristic irreverent tone that, “At first, the Shi’a was primarily a political faction-the supporters of a candidate for power, with no distinctive religious doctrines and no greater religious content than was inherent in the very nature of Islamic political authority (the Assassins, 20).” While Lewis goes on to describe Shi‘ism’s gradual acquisition of a religious dimension, it is clear that for him it remains secondary to its essential nature as a reactionary political movement. This form of Orientalist framing of the origins of Islamic communities with Sunnism descended from on high, fully formed and primordially constituted. They represented Shi‘ism as splitting off from an imagined orthodoxy, and it was until relatively recently a ubiquitous feature of introductory textbooks on Islam. And this framing continues to, in no small measure, shape the public discourse on alterity and difference among Muslims. Does our adherence to the language of “sectarianism” in part explain the persistence of these ideas in spite of the publication of a number of excellent works by scholars such as Maria Dakake, Najam Haider, Wilferd Madelung, and others that have successfully shown the religious content (e.g. walayah) of both proto-Shi‘ism and proto-Sunnism? After all, these scholars demonstrated the ways in which these distinctions were mutually constructed and shaped through social and discursive exchange, ritual and regional differences.

“Is it our use of the concept of “sectarianism” itself that, for example, leads us to minimize the ways in which Shi‘i and Sunni social agents engaged in activities of mutual advantage or exchange?”

Is it our use of the concept of “sectarianism” itself that, for example, leads us to minimize the ways in which Shi‘i and Sunni social agents engaged in activities of mutual advantage or exchange? Perhaps a description of relationships of cooperation necessitates a shift away from vocabulary that views the actions of groups that diverge in religious and political commitments as “responses” or “reactions” to the marginalizing forces generated from a normative Sunni center. The study of pre-modern Shi‘i-Sunni relations in particular requires a vocabulary that draws attention to the contested nature of religious authority and the dynamic relationships of power between Shi‘i and Sunni scholars in the pre-modern period. What alternative frameworks can we employ to explain the causes of violence and conflict between groups within concrete historical contexts and geographical locations? To what degree do we assign value and significance to the direct catalysts and immediate precipitating circumstances for violence over the projection of conflict back to pre-existing religious and political differences?

“The study of pre-modern Shi‘i-Sunni relations in particular requires a vocabulary that draws attention to the contested nature of religious authority and the dynamic relationships of power between Shi‘i and Sunni scholars in the pre-modern period.”

For instance, if one were to focus on Baghdad for a fifty year period during the second half of the seventh century AH, one finds that contemporary literary sources often mention the outbreak of violence between Shi‘a and Sunnis following fires and floods, to which factor do we assign causality, natural disasters or the smoldering powder keg of competing religious self-definitions? These are methodological decisions involving the application of competing ontological and epistemological frameworks that can not be separated from the intended function of our question and our own political and ideological proclivities. Moreover, if the typology is maintained, does the term “sectarianism” have utility for understanding pre-modern relationships between Shi‘a and Sunnis for example or even greater potential for gaining insight into the concerns of the architects of this framework?

Against this background, we can say this much about sectarianism: Sectarianism is a discourse generated, framed, shaped by, and mitigated through specific historiographical modalities connected to the legacy of global white supremacist and imperial academic discourses. Research on the biases of the authors of pre-modern primary source texts seldom extend to systematic analysis of the underlying frameworks of the Orientalist scholars evaluating them. In returning to Bernard Lewis, I would like to offer you a description of what he suggests is the Nizari Isma‘ili invention of terrorism:

It was true. For centuries the Shi’a had squandered their zeal and blood for their Imams, without avail. There had been countless risings, ranging from the self-immolation of small groups of ecstatics to carefully planned military operations. All but a few had failed, crushed by the armed forces of a state and an order that they were too weak to overthrow. Even the very few that succeeded brought no release for the pent-up emotion that they expressed. Instead, the victors, once invested with the panoply of authority and the custodianship of the Islamic community, turned against their own supporters and destroyed them.

Hasan-i Sabbah knew that his preaching could not prevail against the entrenched orthodoxy of Sunni Islam-that his followers could not meet and defeat the armed might of the Seljuq state. Others before him had vented their frustration in unplanned violence, in hopeless insurrection, or in sullen passivity. Hasan found a new way, by which a small force, disciplined and devoted, could strike effectively against an overwhelmingly superior enemy. ‘Terrorism’, says a modern authority, ‘is carried on by a narrowly limited organization and is inspired by a sustained program of large-scale objectives in the name of which terror is practiced,’ This was the method that Hasan chose-the method, it may well be, that he invented (The Assassins, 130.)

There are many things to be learned from Lewis’ colorful account, however few of them are instructive for identifying the causes for Ismaʿili violence during the fifth century AH. However, shifting the focus to analyzing his historiographical framework is suggestive of potential new directions and avenues for more in-depth studies of the very concept of “sectarianism” and its relationship to Orientalism as embedded within a particular framework of whiteness and white scholarship on Islam and Muslims in the twilight of North American and European imperialism. The anachronistic retrojection of conflict between Shi‘a and Sunnis devoid of political, social, religious context, and catalysts is an Orientalist trace –whose excavation could perhaps foster greater insight into the enduring legacy of both Orientalist historiography and contribute to contemporary scholarship on whiteness and post-Orientalist white politics.

[1] Ignác Goldziher and Bernard Lewis, Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 168.